An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Oral History Interview with Paul A. Shackel

An Archeologist as Applied Anthropologist:

An SfAA Oral History Interview with Paul A. Shackel

Paul Shackel’s career as an applied archaeologist starting with posting with the U. S. National Park Service (NPS). After extensive experience with the NPS, especially at the Harpers Ferry National Historic Park in West Virginia, Shackel joined the faculty in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Maryland where he served as chair for 12 years until June 2020. The interview shows some of Shackel’s involvement in the emergence of a societally engaged American archaeology over the past three decades.The interview was done by Michael J. Stottman on January 11, 2020. They both share a commitment to civic engagement and application in historical archaeology. This interview was transcribed using Otter.ai [https://otter.ai] on-line software. The result was compared to the audio and edited for accuracy andreadability by John van Willigen.

Paul Shackel’s career as an applied archaeologist starting with posting with the U. S. National Park Service (NPS). After extensive experience with the NPS, especially at the Harpers Ferry National Historic Park in West Virginia, Shackel joined the faculty in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Maryland where he served as chair for 12 years until June 2020. The interview shows some of Shackel’s involvement in the emergence of a societally engaged American archaeology over the past three decades.The interview was done by Michael J. Stottman on January 11, 2020. They both share a commitment to civic engagement and application in historical archaeology. This interview was transcribed using Otter.ai [https://otter.ai] on-line software. The result was compared to the audio and edited for accuracy andreadability by John van Willigen.

Stottman: We're at the Society for Historical Archaeology meeting in Boston,Massachusetts. And I am Jay Stottman. I’m doing the interview, interviewing Paul Shackel. Paul, so you were at the very beginning of this idea of doing civicengagement and activism and those kinds of things that we have in archaeology right now, that have become very prominent in taking the past and connecting it with the present. And so we wanted to get an idea of what kind of influences you had. Where did it start for you? Was there anything in how you were raised? So let's start with that.

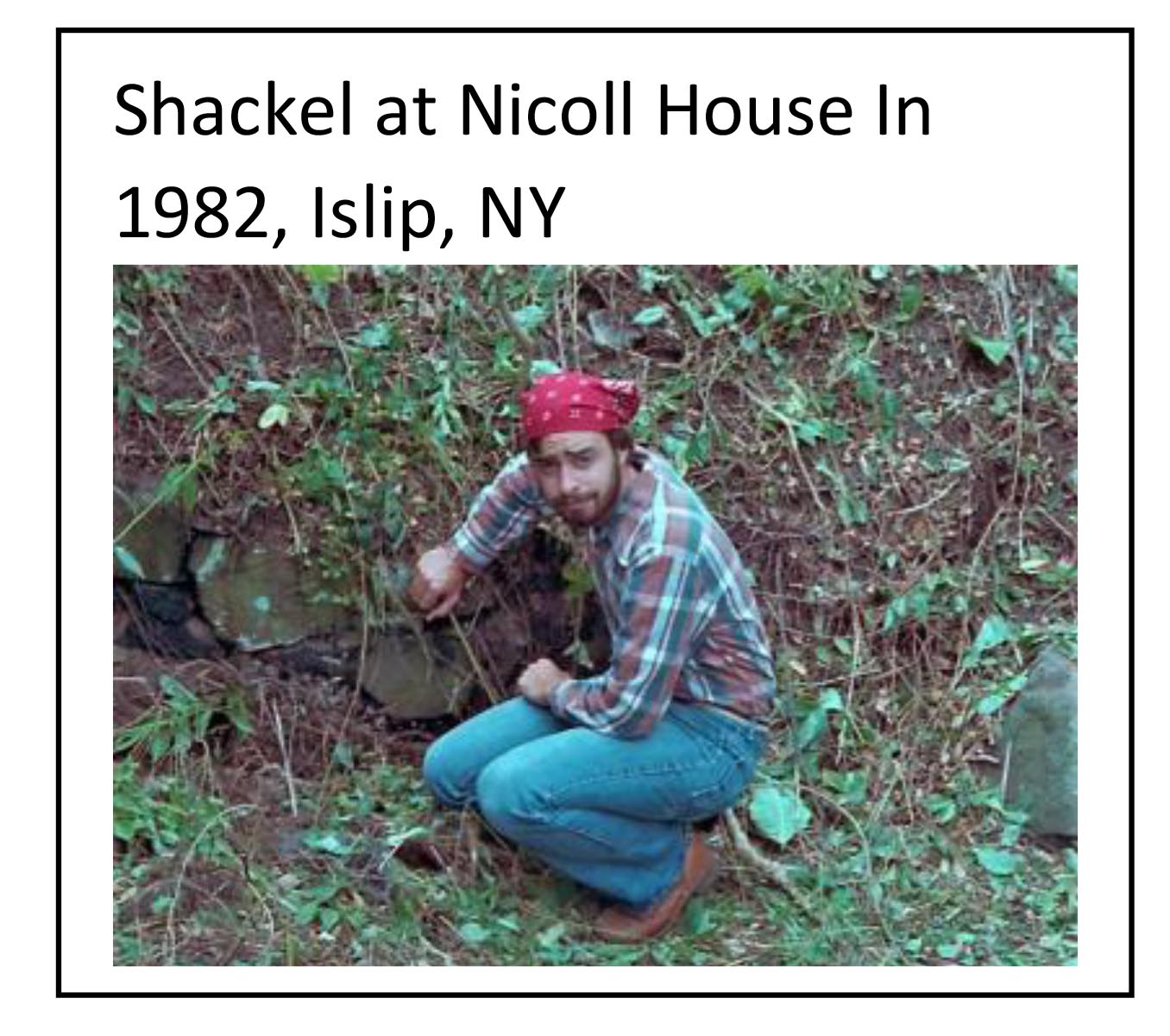

Shackel: I'm not sure it's how I was raised. But it was my journey through archaeology. So, when I initiallywent to graduate school, my goal was to do prehistory. I went to the University of Buffalo, and I was very interested in working with the Iroquois and working with the Jesuit Relations and so forth. And then one summer I had an opportunity to do some historical archaeology onLong Island, which became my master's thesis and that gave me the credentials as a historical archaeologist. I was able to put that on my CV, then eventually I applied for a position for the Archaeology in Annapolis project working with Mark Leone. And so my whole focus shifted from working in Northeast or Western New York to doing historical archaeology. So it was sort of a seismic shift. So it was actually working with Mark Leone that made me think about the public, and thinking about outreach to the public. And mind you, this was all in the early 1980s, and in the early 1980s people sort of mocked Mark Leone for talking to the public because the positivist agenda was very strong, and we were scientists. You know, there was the feeling that we were scientists, and we should control the narrative. And in some ways, Mark Leone’s interpretation was controlling the narrative. He was creating, a narrative about the archaeology site, but he was sharing it with the public, which was something rather new and groundbreaking in the discipline of archaeology. So I worked on the archaeology project - Archaeology in Annapolis project - for several years. And that always stayed with me - the importance of the public. And when I got my first job in the National Park Service that was also a struggle. I tried to bring those ideas about public archaeology to the National Park Service. And I followed in the tradition of some archaeology at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, where people actually, or where archaeologists actually put-up signs that said, “we're doing archaeology don't bother us.” Right, and so I eventually became the park archaeologist and we started to put placards out when we were doing archaeology, and we would also have archaeologists jump out of the test unit to greet visitors. I got some pushback from some people in the National Park Service, but the interpreters in the interpretive division loved it. Right. And so there was at that time a very strong division of interpretation at Harpers Ferry. And so, in some ways, there was a bit of a struggle or a bit of a clash while I was working at Harpers Ferry about reaching out to the reaching out to the public. But I think, thinking about the literature and thinking about where the discipline was going in the 1990s, I'm thinking about the NAGPRA [Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act]movement, you know, where American Indians now had a say in controlling their material culture, and thinking about the African Burial Ground [in New York City,] that was pretty seismic in the discipline -- thinking about how the community got control over the message and the archaeology. Those were two major events in my career - thinking about people in public and doing more than just reaching out and telling the story. But then getting people involved, and getting people involved in telling the story. So those were, I think, key events in making me think about the power of archaeology. I don't really see archaeologists surrendering power, but I see archaeologists becoming partners in creating the power of the message, and you need the public in order to get the message across. And so, in 2004. I was lucky enough to get a grant from the National Science Foundation to work in Illinois, and I had two great partners, Terry Martin from the Illinois State Museum and Chris Fennell from the University of Illinois.

And as an experiment, we went out there and we had community meetings in 2004, and we started working in New Philadelphia, that's the New Philadelphia project. We had community meetings and we asked the community - What did they want? What do they want us to find out and that helped us create a research design, going forward? I thought this is pretty cool. You know, getting the community involved in, and then later on we actually changed our research design as more of the community and more of the descendants became involved in the project. And so we were flexible. The initial goals were about finding out more about the town and the people in the town, and so forth. And then, when the African American community got involved, they said, you know, we don't want to hear about slavery, we want to hear about freedom. So that really changed the way we started thinking about that project and how to interpret the project. So that was groundbreaking I think for me - thinking about how to get the public involved, but it was also very enriching. It was very satisfying to do that. It had its bumps along the way. No road is without a pothole, but in the end, it was rather rewarding. And so we've been able to get the New Philadelphia site on the National Register [of Historic Places] and now it is a National Historic Landmark. And we're working to make it a National Park Service site. Parts of the collections are in two Smithsonian exhibits - one in American history and one in the African American Museum [of History and Culture]. So the story is beingtold, and I think a lot of the reason why it's there in those museums is because of the public. The community embraced the project, and it got a lot of publicity for that and people paid attention to it, and it became part of the story of migration. So it wasn’t a story about slavery, but it was a story about migration and this free African American who moved west. So, since then, in about 2009, I began a project in northeastern Pennsylvania, and it took a slightly different turn. In this case, we worked closely with the local community in finding a massacre site, the Lattimer massacre site. [Editor: The Massacre occurred in 1897 when 19 striking unarmed coal miners were killed by local sheriff deputies near Hazleton, Pennsylvania.] And it was actually done electronically.We set up a webpage and we said we're very interested in knowing more about northeastern Pennsylvania and learning more about Lattimer and what happened at Latimer. There were a lot of these old timers who had families in the community for generations who actually got in touch with us and said we're interested in helping to locate this site and, and perhaps we can work together. Then we went up there and we started talking to them. Eventually, we were able to do a survey and find the massacre site. Mike Roller was a graduate student at the time, whoactually contacted Dan Sivilich, who is in charge of BRAVO, which is the Battlefield Restoration Archaeology Volunteer Organization. They are a metal detecting group that worked with the National Park Service to find battlefield sites. So Mike placed a message on HistArc [listserve for the Society for Historical Archaeology] and noted that we're interesting in doing a metal detector survey here. Can somebody help us? And within 20 minutes Dan Sivilich contacted him and said “you know I'm the first generation not to go in the mines. We'll help you.” He was just great. So, for me it's been rather rewarding, working with the community and the issues of labor in northeastern Pennsylvania. We're one of the few people or few archaeologists to actually have a sustained archaeology project up there. And people are so grateful that somebody is paying attention to them because northeastern Pennsylvania, is part of NorthernAppalachia. And there's a lot of poverty there. And there's not much [Section]106 [of the National Historic Preservation Act] compliance work up there. There is not much archaeology and people haven't paid much attention to the local history there. So, even though we're writing about northeastern Pennsylvania and some of the issues of racism in northeastern Pennsylvania people still embrace us, which is kind ofinteresting.

And as an experiment, we went out there and we had community meetings in 2004, and we started working in New Philadelphia, that's the New Philadelphia project. We had community meetings and we asked the community - What did they want? What do they want us to find out and that helped us create a research design, going forward? I thought this is pretty cool. You know, getting the community involved in, and then later on we actually changed our research design as more of the community and more of the descendants became involved in the project. And so we were flexible. The initial goals were about finding out more about the town and the people in the town, and so forth. And then, when the African American community got involved, they said, you know, we don't want to hear about slavery, we want to hear about freedom. So that really changed the way we started thinking about that project and how to interpret the project. So that was groundbreaking I think for me - thinking about how to get the public involved, but it was also very enriching. It was very satisfying to do that. It had its bumps along the way. No road is without a pothole, but in the end, it was rather rewarding. And so we've been able to get the New Philadelphia site on the National Register [of Historic Places] and now it is a National Historic Landmark. And we're working to make it a National Park Service site. Parts of the collections are in two Smithsonian exhibits - one in American history and one in the African American Museum [of History and Culture]. So the story is beingtold, and I think a lot of the reason why it's there in those museums is because of the public. The community embraced the project, and it got a lot of publicity for that and people paid attention to it, and it became part of the story of migration. So it wasn’t a story about slavery, but it was a story about migration and this free African American who moved west. So, since then, in about 2009, I began a project in northeastern Pennsylvania, and it took a slightly different turn. In this case, we worked closely with the local community in finding a massacre site, the Lattimer massacre site. [Editor: The Massacre occurred in 1897 when 19 striking unarmed coal miners were killed by local sheriff deputies near Hazleton, Pennsylvania.] And it was actually done electronically.We set up a webpage and we said we're very interested in knowing more about northeastern Pennsylvania and learning more about Lattimer and what happened at Latimer. There were a lot of these old timers who had families in the community for generations who actually got in touch with us and said we're interested in helping to locate this site and, and perhaps we can work together. Then we went up there and we started talking to them. Eventually, we were able to do a survey and find the massacre site. Mike Roller was a graduate student at the time, whoactually contacted Dan Sivilich, who is in charge of BRAVO, which is the Battlefield Restoration Archaeology Volunteer Organization. They are a metal detecting group that worked with the National Park Service to find battlefield sites. So Mike placed a message on HistArc [listserve for the Society for Historical Archaeology] and noted that we're interesting in doing a metal detector survey here. Can somebody help us? And within 20 minutes Dan Sivilich contacted him and said “you know I'm the first generation not to go in the mines. We'll help you.” He was just great. So, for me it's been rather rewarding, working with the community and the issues of labor in northeastern Pennsylvania. We're one of the few people or few archaeologists to actually have a sustained archaeology project up there. And people are so grateful that somebody is paying attention to them because northeastern Pennsylvania, is part of NorthernAppalachia. And there's a lot of poverty there. And there's not much [Section]106 [of the National Historic Preservation Act] compliance work up there. There is not much archaeology and people haven't paid much attention to the local history there. So, even though we're writing about northeastern Pennsylvania and some of the issues of racism in northeastern Pennsylvania people still embrace us, which is kind ofinteresting.

Stottman: We'll drill down a little bit on a couple of these things. So, just to go back to the beginning. Wereyou always interested in archaeology, or is this something that you discovered a little later? And where areyou, where are you from originally?

Shackel: I grew up in the Bronx in New York. I spent the first 10 years of my life in the Bronx and I often identify being from New York. And then at about 10 years old, when I was 10 years old my family moved to Long Island. My father got a promotion and we moved to suburbia. And so, archaeology wasn't even on my radar screen. I didn’t even know what archaeology was. So, going through high school I had a love for architecture. In the last two years of high school I took architecture classes, and then I thought that was what I wanted to do as a career. And then when I applied to college, I put down business major. I don't know why I wrote down business major. I took some courses, including calculus and economics -- and I hated it. I didn’t know what to do. My GPA in my first semester was really bad so I came back home, and I went to a community college - Suffolk County Community College. In my second semester there I took ananthropology course. I took the course because my sister went to the community college too and she said, “Oh, you should take a course by this one instructor – Albin Cafone - and you'll really like the course.” so I took the course and I said, “Wow, this is great.” He was a great instructor and probably the best instructor I ever had in my whole academic career. It was just fun. It was great. And it was more or less old-timeethnography. We read some of the older ethnographies, but we also read some of the newer ethnographies - like by James Spradley – The Cocktail Waitress. I forgot the name of the ethnography about skid row bums, talking about poverty within skid row in Seattle [You Owe Yourself a Drunk]. Are youfamiliar with that one, Skid Row in Seattle? I thought this was really interesting, and I would go to his office after class and I told him I wanted to do something during the summertime. And he gave me a brochure that came across his desk and it was a field school, which was then the Foundation for Illinois Archaeology, which is based in Kampsville,Illinois, which is now the Center for American Archaeology. So I did a field school out there, and I almost didn't return. I just got the bug; it was really fantastic. And that was my turningpoint that got me very interested in archaeology. I worked on the ElizabethBurial Mounds. So imagine working on burial mounds today. It would be apretty tough order.

Shackel: I grew up in the Bronx in New York. I spent the first 10 years of my life in the Bronx and I often identify being from New York. And then at about 10 years old, when I was 10 years old my family moved to Long Island. My father got a promotion and we moved to suburbia. And so, archaeology wasn't even on my radar screen. I didn’t even know what archaeology was. So, going through high school I had a love for architecture. In the last two years of high school I took architecture classes, and then I thought that was what I wanted to do as a career. And then when I applied to college, I put down business major. I don't know why I wrote down business major. I took some courses, including calculus and economics -- and I hated it. I didn’t know what to do. My GPA in my first semester was really bad so I came back home, and I went to a community college - Suffolk County Community College. In my second semester there I took ananthropology course. I took the course because my sister went to the community college too and she said, “Oh, you should take a course by this one instructor – Albin Cafone - and you'll really like the course.” so I took the course and I said, “Wow, this is great.” He was a great instructor and probably the best instructor I ever had in my whole academic career. It was just fun. It was great. And it was more or less old-timeethnography. We read some of the older ethnographies, but we also read some of the newer ethnographies - like by James Spradley – The Cocktail Waitress. I forgot the name of the ethnography about skid row bums, talking about poverty within skid row in Seattle [You Owe Yourself a Drunk]. Are youfamiliar with that one, Skid Row in Seattle? I thought this was really interesting, and I would go to his office after class and I told him I wanted to do something during the summertime. And he gave me a brochure that came across his desk and it was a field school, which was then the Foundation for Illinois Archaeology, which is based in Kampsville,Illinois, which is now the Center for American Archaeology. So I did a field school out there, and I almost didn't return. I just got the bug; it was really fantastic. And that was my turningpoint that got me very interested in archaeology. I worked on the ElizabethBurial Mounds. So imagine working on burial mounds today. It would be apretty tough order.

Stottman: Couldn’t do it.

Shackel: There was a bridge construction project that was happening that was going over the Illinois River. It was an interstate that was connecting to Hannibal. And I remember we'd get up at five in the morning, be on a bus by six. We'd be in the field by seven, come in at four. Shower, eat and then lectures at night. Jane Buikstra was in charge of the field school and she worked us hard for nine or ten weeks for the field school. It was great. I thrived in it. It was a lot of fun. And that's why I started thinking aboutarchaeology and thinking about archaeology for my graduate program.

Stottman: Yeah, I think a lot of us archaeologists have things like that, I mean your background is almost identical to mine, my kind of experience. I didn’t know what it was until I got to college. I wanted to be anengineer. Then the math stuff, you know.

Shackel: Yeah, it was calculus that drove me out.

Stottman: So let's talk a little bit about some of your early influences and you mentioned Archaeology in Annapolis. And I think if you look at the field today and who the people are, we've been doing a lot of this kind of work that we're talking about. You see a lot of those people came out of that program in one way or another. I believe Barbara [Little] was there.

Shackel: Yeah, Barbara was part of the archaeology program. Paul Mullins was part of it, Mark Warner was part of it. Parker Potter, Liz Kreider Reid, Julie Ernstein, went through there. Chris Matthews wentthrough there, among many others.

Stottman: So, that project, I always point to it as a seminal project as far as public archaeology goes. But this was also at the time when you were there, that you and Parker Potter and Mark Leone wrotethe article about critical theory.

Shackel: Yeah.

Stottman: Which was a huge influence on me for thinking about these kinds of things. So theoretically what was going on at that time in relation that project. And the sort of the culmination of this reaction topositivism and in the New Archaeology that was going on, thinking about the influence that the Archaeology in Annapolis project had on the theoretical paradigm shift.

Shackel: Well, I think it carried the flag, or carried one of the flags. Mark Leone has always been a rebel. Even though he was trained as a positivist right, but he was always on the fringe of positivism. And he, I'm thinking about some of his articles about Mormon fences and wrote about the symbolism of fences in the desert. Or his article about the Mormon Temple [in Washington, DC.] where he writes about the symbolism within the Mormon temple - and that's really fringy stuff for an archaeologist. And then he wrote another article about interpreting Williamsburg. So all of these were in the late 70s, early 80s, during a time that you have the English [Cambridge] school with Ian Hodder, and his students who werebanging the drum for a different archaeology. And at sometimes Mark and Ian clashed, but they came together and that's where Mark wrote the article about the [William] Paca Garden, which created a lot of fodder for discussion later on in the discipline and mostly about how to read gardens, and so forth. Whether he was right or wrong. I give him [Leone] lots of credit for just pushing us to think differently, and I think that's what the whole critical archaeology movement was about - getting us to think differently, to get us out of the mold. All these theoreticians that are cited [in the article Toward a Critical Archaeology] they were all new to the discipline back then. Now we have been quoting them for 20 to 30 years. Again myhat’s off to Mark again for reading that stuff and introducing us to all these great theoreticians that made us think about material culture in everyday life very differently. I picked up on [Michel] Foucault which became foundational for a lot of my work. Later on, especially in Harpers Ferry, the idea of always seeing, the panoptic vision, was pretty instrumental in my future work at Harpers Ferry.

Stottman: And your interest in labor.

Shackel: And labor sure. So, it was so foundational in that, too. So the early 1980s, and the materials coming out of the Annapolis school was really the introduction of a very new way of thinking about material culture. And I don't know if it was necessarily anti science, but I see it as more or less providing a different perspective of the way to look at the past.

Stottman: Now that aspect of the Archeology in Annapolis project going on at the same time as this theoretical shift. Was it the theory that was influencing what was happening with engaging the public, or was it the other way around, was it just the mutual sharing because that, you know, one of the things in thecritical theory was about being this idea of reflexivity and in thinking about how our information engages with people in the present? Was Archaeology in Annapolis seen as a laboratory for this kind of thinking or did the engaging in the public, get us as archaeologists to think about these kind of theories?

Shackel: That's a good question. Which came first -the chicken or the egg? I mean that's what you're asking.

Stottman: Pretty much.

Shackel: Right. So that's kind of interesting, I think. I don't know if I have a good answer, but I think whatwas going on at the time was the introduction of this theory with the goal of making everybody more reflexive. But I don't think the Annapolis project, the way it was carried out was necessarily successful at that because we were in the field and we were telling people about what to think about the past and there was very little reflexiveness, or input. But I want to give credit to the Annapolis project for laying thatfoundation for what came a decade later, or, or a little bit later.

Stottman: Parker Potter said as much in his dissertation and later the book. Looking back at that projectwhich for me it was very instructive. There's got to be a sort of a first and as we know in public archaeology there's a lot of trial and error involved. And it's a long time to develop it, but it also takes a reflective eye to look back at it, and analyze it. Where can we improve in evaluation? And I think that's what I got out of what Parker was looking at. And that for me it was really instructive to do that. So, today it wouldn't hold up to today's standards, but we wouldn't have today's standards if we didn't do that.

Shackel: Yeah, and the thing is, we don't really have a playbook necessarily because every situation is different. So, it's always easy to step back and criticize – right? And in a lot of times in doing community archaeology you're inventing on the fly. Sometimes you do it well and sometimes you don't. But there's no real playbook. The real playbook is to engage and engage early, and then what happens after that depends on the conversations you have and the interactions you have - sometimes it’s successful, andsometimes not. I mean you probably know that for sure - doing a lot of the work that you do.

Stottman: Yeah, it's about the process.

Shackel: Yeah,

Stottman: . . . that sort of guides you and you can hold this up with some sort of model, but you can’tguarantee that it will work out.

Shackel: People are interesting, and people are different.

Stottman: I think that's what scares some archaeologists,

Shackel: And it scares mesometimes, too.

Stottman: I agree. And so you talked a little bit about some of the backlash that Leone experienced doing this public archaeology kind of thing. Even me getting to it later than that, and I think we probably still experienced it to some degree -some pushback from archaeologists about getting the public involved. Iwas wondering did you have any experiences in that way, or what are your thoughts about doing this kind of work situated in archaeology -how people react to it, archaeologists are people too and change is not easy for people.

Shackel: It’s not easy. I remember doing public archaeology in the Chesapeake. The Annapolis project was an anomaly. And, you know, there's some major forces in Chesapeake archaeology. And I justremember them being very critical and making fun of the Annapolis project, and I've been talking to some of the alums of the Annapolis project and alums have told me that when they have gone for an interview, they have been told later that they weren't hired because they worked on the Annapolis project.

Right. So that still carries on today, which is really interesting. Somebody just told me that at lunch the otherday.

Stottman: So, when you go to the National Park Service then you are dealing with another kind of sort of pushback within that structure of the Park Service and interpretation when you talk about your experience in the National Park Service you said you were dealing with another kind of pushback – within the Park Service and interpretation. So it's like a battle you have to wage to get this in there to battle these traditional perceptions of what archaeology is and how it should be. So your time at Harpers Ferry that's a non-academic setting. It's one of those places where maybe public archaeology would be more acceptable, which I was kind of surprised you said there was a lot of pushback.

Shackel: So. Yeah. I got pushback from the park historian who said that we couldn't control the narrative about what we were digging. I put in some descriptive words [on a placard at the site] about people beingexploited and so forth and that wasn’t acceptable. And so that was the park’s historian at the time, got a little bit of pushback initially from the interpretive division, it was a large interpretive division. So, we created a program where we would have them [NPS interpretive staff] dig with us. One person, every week would excavate with us. So we got to know them, you know, personally.

They get to see the archaeology going on. And they, more or less, helped us move the interpretationforward with the narrative that we were trying to present.

Stottman: Nothing like working on a dig, you know way too much about somebody right.

Shackel: It happens – right. You're in a test unit with somebody for eight hours, and you're going to hearsome stories.

Stottman: More than you want.

Shackel: But that ended up being a key strategy in creating an alliance with the interpretive division, and they helped us put on programs. We had an archaeology weekend that they helped us develop and we were able to get our message out about capitalism and the impact of capitalism on the people who worked in the armory. So that was that. It was really interesting and that was the foundation for my book - CultureChange and the New Technology - which was published, I think in 1996 and the premise of that bookbecame part of an exhibit at Harpers Ferry which is still up there.

25 years later, it's still up there in the park.

Stottman: How long were you at Harpers Ferry?

Shackel: I was there for seven years. I got there in May in 1989 and I stayed there until January of 1997when I shifted over to the University of Maryland.

Stottman: Right, I actually wrote to you and requested a copy of the couple of the reports at Harpers Ferry.

Shackel: Did I send them to you?

Stottman: You did.

Shackel: Okay!

Stottman: So, at Harpers Ferry, you mentioned that the exhibit is still there. The things that sort of different sort of way of looking at archaeology and how it fits with the interpretation. Do you see that continued? Did that change anything or was it just because you were there.

Shackel: Both. I think the answer is both. I say both because some of the people who worked on the project are still there, and they still carry the message. In what we did back in the 1990s we put the focus on people and placed the focus on capitalism. Some of the newer exhibits are like that. But I also think that once those folks leave that message is going to disappear. It depends on who's there. So right now the folks who worked on the project and the folks who I trained, are there and they’re working on it. It'ssurprising to me that the exhibit that we helped to create back in 1996 is still up there.

That is also a statement about the National Park Service - about not modernizing and keeping up with the times. But the message is there. And to me it's quite amazing because maybe 400,000 people go to Harpers Ferry every year. And I would say maybe 10% of them probably go into that exhibit and look at that exhibit, which means 40,000 people are looking at. That's powerful outreach and I think that's the power of working in the public sector. Working in the National Park Service you could reach so manymore people and influence the way people think about the past as well as the present. It’s just amazing to me and I'm very pleased that it's still up there and that the message is stillthere. It's pretty powerful.

Stottman: So, from that government National Park Service job where did you go after that?

Shackel: I went to the University of Maryland. I applied for the position at the University of Maryland because I was on term positions at the Park Service. I think if I had a permanent position at the Park Service, I'd still be in the Park Service. But my term was running out. I was on my second [4-year] term - on the third year. A position was open. And I think what was key was that I've been publishing along the way. And I put out several books and several edited volumes and that gave me the credentials to apply and to compete successfully at the University of Maryland. So when I first got to Maryland, I worked with the National Park Service on several projects - including Manassas [National] Battlefield, and Matt Reeves was one of the folks that we hired initially to work on that project. And then we had a long-term project, three or four years, at Monocacy National Battlefield. And, and a lot of graduate students were trainedthere: Sara Rivers-Colfield who's now on the SHA board of directors worked up there.

Stottman: I worked with her. She was an undergraduate at Murray State. So I worked with Sara whenshe was an undergrad.

Shackel: She earned her master's and she worked up there with Joy Beasley who's now the Associate Director of Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science at the National Park Service. Brandon Beis who's now the superintendent at Manassas, worked up there, and a few other folks too.

Stottman: So when you made that transition from the Park Service to the academic setting of the University of Maryland it sounds like you brought some of those things that you learned or were already doing at the Park Service to that context? That academic context versus that government Park Service context. How do those compare as far as supporting that kind of work?

Shackel: Can you rephrase that? How does that public work, translate into academic work.

Stottman: Right, I mean did you find it was easier to develop projects within that academic context, versusthe government context, or was one more conducive to doing that kind of work better than the other, or theyhave both positives and negatives?

Shackel: I think working for the National Park Service helped me in the transition into academia and working on these cooperative projects with the National Park Service. So I think it gave me some credentials to do these co-op projects. But I also had to hire good people to do it, too. I understood the Park Service. Well for a long time I got a lot of contracts with the National Park Service, cooperative projects, to work in the national parks, and it was because of my credentials. So, the issue is how does that translate into academia. And for the most part people didn't criticize that. I think mostly people were supportive of that as long as I was able to publish in peer reviewed journals. That was okay. At the time in 1996, 1997, 1998 I am thinking, people didn't really pay much attention to the Department of Anthropology at the University of Maryland and what people were doing in it. We weren't on people's radar screens. And so I think it was easier for me to do that [public engagement]. I think it would still be easy today. So there's the standard of publishing and publishing in peer reviewed journals, it was paramount, back thenand it still is today. I don’t know if that answers the question.

Stottman: It does, I mean, with what I'm getting at is the demands of publishing, does that make it more difficult to develop a sustainable, long term, investing the time and effort into developing the relationships you need to do public, civic engagement with these kinds of projects, especially the sustainable projects that you've done, and which I think really separates the kinds of things that you've done from a lot of other of such programs, your ability to be able to do it for so long and to keep it going for so long. Is that attributable to something that was supported by the university or did you encounter any difficulties there?

Shackel: I didn't have difficulties, but I wasn't necessarily supported. In academia you're on your own. And so I always tell people that I really enjoyed working for the National Park Service because people worked as a team. I worked with historians and landscape architects and architects and interpreters and we always worked on a project as a team. In the academy you're on your own, and you have to develop whatever you need to be successful. And so, support, I don't think I necessarily got the support that I needed or should have gotten, but that also made me work harder to try to sustain these projects, but the projects that I've done, these long-term projects, are just amazing and wonderful projects that you just can't put down after a year, because there's so much to do. The New Philadelphia project – there was so much to do. What I'm doing in northeastern Pennsylvania there's so much to do. Few people have touched northeasternPennsylvania and the coal mining history and dealing with issues of poverty and racism and so forth.

Stottman: Did you find colleagues that were interested in the same kind of thing, I know the book you did with Erve Chambers. Did you find University of Maryland having a fairly strong applied anthropology program dovetails with the kinds of things that you were trying to do.

Shackel: So Erve Chambers is a cultural anthropologist and he actually made the outreach to me and said, “we should do this [edited volume on applied archaeology] and he was always very interested in tryingto create a bigger presence of archaeology in the Society for Applied Anthropology. There is not much of a presence in the Society today. We made some attempts to do that in several instances. But I gotpushback from archaeologists for working with Erve Chambers on that book. And I think part of it was, I think is that “applied” in the title of the volume. There are archaeologists who gave me some pushback because the word “applied” and they don't think that archaeology should be applied. So it's still continues, and the book is now 15 years old. But that's sort of what I confronted. At the time, you know, working with the cultural anthropologists and in developing that.

Stottman: Did your collaborations with culture anthropologist affect your programs, or how you thought about your programs, or was it more of a sort of a mutual interest in people who are living?

Shackel: I think I benefited from working with cultural anthropologists. And I think that's why I can't do an archaeology project without thinking about cultural anthropology, without thinking about ethnography. Even with what you do you have to talk to people and that's all based in cultural anthropology, we're all doing a little bit of ethnography, either formally or informally. And it added a nice dimension to what I do, and I thinkit's a nice dimension what people do in the field of archaeology today. So I think it's been a benefit working withother people in other sub-disciplines. In fact, I make sure that all my students now take an ethnography course, because you have to talk to people. The old saying back in the 1970s and 1980s is “I became an archaeologist because I didn't want to talk to people.” And you can't say that to me anymore. You can't be one of my students and say that. You have to be out there on the ground, talking to people, and getting asense of the community before you work in that community.

Stottman: Right. So, do you think that with this emphasis on archeologists being more engaged with living people do you find that brings archaeology back into what it is to being anthropologists, because there's always been that natural sort of divide between cultural anthropology and archaeology. Do you think that gives them some common ground that makes things seem a little more collaborative?

Shackel: Yeah. Collaborative is good, are the dividing lines broken? I don’t think completely, it depends on where you are. So at the University of Maryland students come out thinking it's pretty natural to work with cultural anthropologists, to do ethnography. I'm not sure what it's like in other places, but my students come back and tell me when they meet folks at the conference from different institutions that their training is very different than what they're getting. So there is a divide in the discipline, you know. We're going to train students differently at the University of Maryland, hoping to break down the divide. I think within the department; the divide is broken down. We don't have the schisms between the different sub disciplines. People grabbing for money versus another subdiscipline. We're working together as a department, so I think the way we train our students also reflects in the way in the culture of our department and the way we get along in the department.

Stottman: That’s the perspective I have trying to show the similarity in the kind of work that archaeology can do that’s very relatable to cultural anthropology colleagues, and applied anthropology colleagues. We have good conversations about that. I like the sense that you're training your students in those anthropological ethnographic methods, you know, that they're going to need as archaeologists in the 21st century. Again, these are skills that you have to have.

Shackel: Okay. And even if they don't become archaeologists it's still skills that you need. If you becomean architect or a banker, you need to figure out how to read people and understand people. It's a good lifelesson.

Stottman: Definitely, so some applied anthropologists see archaeology as a domain within applied anthropology. As an application of anthropology. And you mentioned that before and I would agree. Many archaeologists probably don't see it that way, but you personally do you see that sort of relationship how archaeology fits within anthropology as an applied aspect of it.

Shackel: I think it is applied. I mean, it doesn't necessarily have to be, but I think it takes an effort to be applied. So you know within this Society for Applied Anthropology there’s a big debate, whether applied is a fifth field or if it should be within one of the sub fields. And really - I don't care, you know. But that battle rages on within the discipline. But I think thinking about archaeology as applied is an important step in making the discipline relevant, relevant to the discipline, but also relevant to the larger public too. I don’t think we can erase that from what we are doing. I think it's important to train our students to think about archaeology as applied on a lot of different levels of being applied. Applied as in doing Section 106 [of theNational Historic Preservation Act] work, applied in working with communities, applied as in working with other disciplines. So, I think it's an important part of the discipline, you know, thinking about archaeology about being applied.

Stottman: And with that same regards something I had worked on recently was on an entry on applied archaeology for this publication. It got me really thinking about what is applied archaeology. What do people think about that and I would tend to group all that stuff that we do from cultural resource management which is the traditional definition of what applied is, to include all the things of civic engagement and activism, that we've been talking about. More recently and I was wondering what your thought about what applied archaeology is. And I know this is like a really big, difficult thing to put under this umbrella. I just wonder what your thoughts, what that means to you. Now, what applied archaeology means now. Even if we should even use that term. That might be a better question.

Shackel: I don't know. I mean I haven't really thought about - should we get rid of the term appliedarchaeology. That's a good question. I don't, I don't know. I would probably agree with a lot of what you wrote about applied archaeology, which is from traditional CRM, all the way up to civic engagement. It's a pretty big, broad field. So I could also see applied broken down into different categories.

Stottman: I think I landed in the sense that, that it means all those things. it's probably not even a really relevant term right now. In fact, I think it sort of disappeared for a while, and then it's a kind of coming back with all this attention to engagement. Yeah, that's why I'm asking because I don't know where it lands. The more that I do this kind of work, the more I see that we struggle with terminology.

Shackel: I was just going to say that. I try not to pay attention to it as much.

Stottman: It’s really not that important.

Shackel: The real important thing is doing good work. Right. And whether you're going to debate whether archaeology is applied or not, I don't care. Right, yeah, it's about doing what's important, and somebody else could debate whether it’s applied, is this a relevant term to what we do, or not. But the thing is, keep on doing and thinking about your work and thinking about social justice issues and how do we make archaeology applicable to current living conditions, you know that that's important. And so let somebodyelse discuss that. I don't care what you call it.

Stottman: I just really found very interesting our obsession with this terminology. We always have these discussions and it really matters what we call it as long as we're doing it and I see that you still feel the same way. One thing I noticed in doing this kind of work and especially working with some students is that when students come in, and I'm speaking from my own experience, [them] asking that question – “why do we do archaeology?” Why do we do it? I am sure when you were coming out. I was always told - because the law says we need to do it, from the CRM world. And I was like, that's not good enough. There's got to be a better reason and I think a lot of students come in with that idealistic notion, because you're idealistic when you're a student - that notion that archaeology can be used for something, for the betterment of the world. And, at some point in the past seems like those things would get lost, or not focused on. Those kind of things. And I was wondering how when your students when they come into your program now. Do they recognize those kinds of things? Is that…I’m sure the way you think you embrace those kind of things thatyour students would want the archaeology that you do can mean something. I was wondering If you had any thoughts about the students who are coming in and what you are trying to instill in them and foster - those things that they that they might wantto see in their archaeology.

Shackel: So what you touched upon, the idealism of a student, is really key. And before we accept students, I interview the students before we accept the students. And I want the student to want to change the world. Yeah, and I look for that in the interview. “what do you want to do?” And I look for hints and I look for clues. And I look for that idealism. And that's key, I think. And so, so whether they leave the program thinking that or not that's up for debate. But I'm looking for students who want to make change. Not just todig up stuff and catalog it and say there were X amount of vessels here, and people were poor or richer here. How are you going to mobilize your discipline and how you going to work for change? And that'swhat I'm looking for.

Stottman: Do you find that students really react to that? In academia really it is a lot about how many students you have, how many majors you have and those kinds of things. Do you find that’s appealing to that aspect of students giving them an opportunity, looking for those sorts of students that helps bring in more students, or get more students interested in anthropology, in archaeology?

Shackel: I don't know if it helps bringing more students in, because every student has a different idea about what archaeology is. But what it does is it helps shape the narrative of our department and the people working in the department. And that's what we want our department to be known for - people who want to make change. And then they become good citizens of the discipline when they graduate. You see a lot of our students from Maryland are very active in a lot of parts of the Society for Historical Archaeology.

Stottman: I’ve met a lot of them.

Shackel: They want to make change. Most of them who you have met still are probably bright eyed and bushy tailed and want to make change. So, that's what we look for when we're recruiting graduate students to the program. It is my hope that we continue that. And that they are still are optimistic and idealistic and think that they could make change - because you can.

Stottman: That's an important step, just knowing that you can affect the world in some way.

Shackel: Yeah, so it's been a blast.

Stottman: Well, so, that's it for all the questions I have, do you have any final thoughts or anything elsethat you would like to add about your career, about the field, in general, and where we're going, anythinglike that?

Shackel: No, I, I feel pretty lucky, about where I am, and my journey through my career. Thirty years ago I never thought I'd be sitting here talking to you, which is kind of a blast, and I almost feel like I'm too lucky -about my career and where I've ended up.

Sometimes I feel like an imposter. So it's been a blast. I feel very fortunate. I have had ups and downs along the ways, and we talked earlier about some of the struggles and the pushback I experienced along the way. But I'm very pleased where I am, I'm pleased, where my students are, and I'm pleased they're in a position to make change on all different levels in the discipline. I feel blessed that I have a great partner -Barbara Little. She's been my biggest critic, yet biggest supporter. So that has made a big difference in the way Ilook at life and look at the discipline. So she's been probably the most influential person in my career in feedback and so forth. So I feel very fortunate where I am on a lot of different levels.

Stottman: So when you come to this year's SHA conference, and you see the symposia and the forums and the topics that are being presented, compared to say, 20 years ago, I don't think you could walk into one of these rooms and not see some sort of discussion about engagement, or public archaeology, or outreach to community. What do you think about that?

Shackel: We've come a long way. Yeah, we've come a long way.

Stottman: Yeah, I was just amazed. You look at the program - there are so many. There's so many sessions about the humanity or public archaeology that they're going on at the same time and you can'tgo see them all.

Shackel: Yes, and there is one this afternoon.

Stottman: Yeah, I’m presenting at that one. Well Paul, thank you very much, and I really appreciatetalking to you and getting to know you better and recording this for posterity, because I think the work thatyou've done, is definitely worthy of that

Shackel: Well thanks Jay for taking the time. Further Reading

Leone, Mark., Potter, Palmer., and Paul A. Shackel. 1987. Toward a Critical Archaeology [and Comments andReply]. Current Anthropology, 28(3), 283-302.

Shackel, Paul A, 1996. Culture Change and the New Technology: An Archaeology of the Early AmericanIndustrial Era. Plenum

Shackel, Paul A. and Erve Chambers. 2004.Places in Mind: Archaeology as Applied Anthropology. NY:Routledge Press,

Shackel, Paul A. 2010. New Philadelphia: An Archaeology of Race in the Heartland. Berkeley:University of California Press.

Shackel, Paul A. 2018. Remembering Latimer: Labor, Migration, and Race in PennsylvaniaAnthracite Country. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Cart

Search