An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Mapping Contexts of Vulnerability in the Time of COVID-19

Funding: This project is funded by a (SSHRC) Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Canada, Explore Research Assistant Grant which supports graduate student team members who maintain the map.

University of British Columbia, Ethics ID: H20-02179.

A good deal of information about COVID-19 comes to public view through statistics of cases, recoveries and deaths, often presented on a global map. Quantitative approaches speak to demographics of harm but not to the escalation of harm as a function of diverse, overlapping situations, events and / or processes. Our project was born in the sudden turn to remote methods and the obvious necessities of global solidarity wrought by pandemic realities. In March 2020, in a graduate methodology course, conversations turned to the effects of the pandemic on people with whom we work just as the bottom fell out of graduate student fieldwork. Our course work included attention to digital mapping projects and various solution-based projects underway that utilize GIS. Given the circumstances, digital mapping offered real-time possibilities to connect networks of researchers as they engage with questions about structural inequalities and the increasingly complex conditions that exacerbate harm.

Our collaboration among faculty (in Canada and Australia) involves a qualitative methodological approach that was realized through co-design with graduate student mappers at UBC. They developed a platform to display online surveys that upload directly to a global map that is visible on our project website. We launched a beta version in May 2020. While contributions are on-going, we are currently designing a second survey that includes Extreme Weather Events. Ecologies of Harm is an open access project that seeks to contribute to dialogues about the social determinants of health and other circumstances that are linked with structural inequalities. As work intended for the commons, information populating the map may be drawn upon, enlarged and engaged by those within and outside of academia.

Project Description:

“… [T]here is absolutely no participation outside if you are there on the scene where history is unfolding” (Marcus 2010: 257).

Researchers, advocates and other witnesses are well positioned to identify conditions that have made life harder for certain groups of people during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the context of a health crisis, populations and struggles may sometimes be universalized through the use of standardized language, metaphors and biomedical description (Varma 2020:2). Focusing instead on the “convergence of complex, interrelated problems” (Balzer 2020:118), we seek brief accounts in locally-relevant idioms when possible, using languages, concepts and culture-specific categories. Our intention is to generate an ethnographic archive built upon global networks of collaborating researchers, advocates and others who are community-engaged. Ethnographic descriptions both identify contexts comprising variable “ecologies” of harm and also complicate the ways that “vulnerability” is defined by attending to descriptions offered by those who identify with such situations.

We recognize “ecologies” as the intersecting contexts that exacerbate suffering and increase exposure to the possibility of harm. This includes but is not limited to: armed conflict, climate change precarity, various states of dispossession, encampment and, pre-existing colonial /imperial structures. The project is also exploring consequential actions or processes initiated in the “shadow” of the pandemic (e.g., lifting environmental protection laws). Our medium of mobilization is a densely annotated, global map that we anticipate will become a kind of living, emerging archive. The online map enables the visibility of inequalities often outside of mainstream view as well as solidarities and grassroots projects that have coalesced to address critical needs throughout the pandemic. In addition, we seek to generate opportunities for collaborative dialogues and solutions-based engagements among diverse networks of witnesses. Ecologies of Harm is located at a contemporary fulcrum of “urgent anthropology” that is, politically-engaged, community-based research mobilized in response to a situation of exigency (Yadav 2018; Balzer 2020; Bermant and Ssorin-Chaikov 2020; Kaptan 2020). We approach “vulnerability” as a quality or state of being exposed to and/or unprotected from the possibility of harm; as occurring within a cascade of (experienced and possible) situations that are historical, social, political, environmental etc.

“Vulnerability”

“Every life, every agency, is susceptible to being exploited or betrayed, or threatened by wars, immigration policies … In reality, vulnerability exists only in situations” (Ferrarese 2016:154).

We are attentive to the use of “vulnerability” as a label over-attributed to particular communities (such as Indigenous peoples and impoverished neighbourhoods). We thus use the term to reference the experience of constantly active, structural pressures that are “embedded in the political and economic organization of our social world”– structures that “conspire to constrain individual agency” (Farmer et al. 2006:1686). We recognize that vulnerability equally describes “existential state[s] of unpredictability, of living without security” (Hundle 2012:288). Clearly, individuals and collectivities carry different burdens and may have fewer options due to historical and contemporary processes that perpetuate inequalities. Disseminating some information may be experienced as stigmatizing by those whose experiences with COVID-19 evoke painful histories and / or contemporary realities of incessant racism and other forms of oppression. To counter stigmatizing and overly generalized definitions (Das 2007), we focus on “textures of vulnerability” eliciting ethnographic description as it attends to “the concreteness of need and the singularity of lives” (Han 2018:340; Butler 2016). Our project honours this specificity by inviting those with experiential knowledge, long-term engagements in community-based research and, analyses of the larger contexts of power that affect local dynamics. Recognizing debates in anthropology that have long problematized “witnessing,” we locate our project among other present-oriented approaches to public scholarship (see Marcus 2005; Sanford and Angel-Anjani 2006; Fassin 2013; Reed-Danahey 2016).Cognizant of the possibility that people are or may be experiencing grief, illness, and /or other kinds of duress, we urge contributing collaborators to submit respectful forms of representation based on their professional ethics. As privileged scholars in what Laleh Khalili (2011) calls “transnational epistemic communities,” we acknowledge that the project may include practices that reproduce knowledge hierarchies, privilege funding networks and other asymmetries of power. With this in mind, we hope to contribute to solutions-based engagements that recognize “participatory communities of congruent rather than shared, intent” (Goff 2001:11). Our process acknowledges uneven fields of power and agency by prioritizing qualified researchers / activists and other witnesses who may best represent themselves. This may include: university and non-university-based field researchers; culture workers; public advocates and policy analysts; health care workers; and, service agency personnel, etc. The live survey link circulates only through networks of researchers /advocates and other witnesses who will register with the project (by email), and who agree to abide by accepted ethical codes. The surveys are also designed to be completed through dialogues among and with interlocutors / colleagues in various locations.

Mapping Knowledge: Online Surveys

We imagined initially, an atlas of sorts populated by various descriptions as they are created through multiple, small collaborations. Our intention was to generate networks of interested contributors (whom we would connect), to engage in conversations about the production and flows of social knowledge in the pandemic context. To date, the map includes submissions by advocates and activists, by fieldworkers in various career paths and by their interlocutors. As political and social tensions have risen in many locations, increasingly, we receive contributions from scholars opting for anonymity. We currently have two short, web-based surveys. The Public Information Survey consists of six questions as well as options to include links to media and other references, upload audio, or, upload video or an image. This survey publishes directly to the map and is publicly visible on our project website. Recognizing that some information is sensitive, we designed a separate Sensitive Information Survey using Qualtrics that allows for information to be submitted to an archive on a secure server in Canada with access limited to project members (rather than the public). This survey includes the option to indicate where the information might be sent for consideration and response.

Phase 2 of the project introduces a citizen survey focused on Extreme Weather Events. In June 2021, those of us who are residents of British Columbia experienced a Heat Dome. The high-pressure system compressed layers of air, resulting in an immovable vault that trapped-in temperatures reaching 49.6 degrees Celsius. 569 heat-related deaths were recorded in the province; 445 of those people died during the seven-day, extreme weather event. Social isolation exacerbated by the pandemic; pre-existing conditions, age, disability and poverty are among the factors discussed in the aftermath (Human Rights Watch 2021). Our Extreme Weather Event survey seeks descriptions of the subjective experience of such events, asking also for people’s perceptions of what social contexts most affect them /others. Importantly, we are interested to hear about ways these events affect their ability to stay safe in the larger context of the pandemic. We anticipate that this survey will present fewer obstacles than professional reportage; that responses may elucidate overlapping states of insecurity and point to needed resources and supports given the uneven capacity to respond to rolling crises. Project mappers are finalizing this layer of the map.

From the Mappers (Maya Daurio and Stephen Chignell)[1]

Our project complements statistical renderings of COVID-19, encouraging us to reflect on the lives beneath the numbers. In line with principles of counter-mapping, our research illustrates how harms caused by the pandemic intersect with other injustices and with specific geographies to exacerbate vulnerabilities of marginalized populations. We created a highly customized survey using Esri’s Survey123 comprising questions eliciting text responses, multiple choice selections, and a map of the world where respondents could plot their location. Survey123 creates a hosted feature layer of the survey responses in ArcGIS Online, and the location information is used to plot point locations of survey responses on a global map. When a new survey is submitted, the map is automatically updated. Because we are interested in how the pandemic changes in relation to time and space, we enabled time settings on the hosted feature layer in order to visualize these submissions over time via the Time widget.

Although our research project collects primarily qualitative data, we were able to configure several widgets that allow map users to interact with the survey responses in multiple ways. In addition to standard navigation widgets enabling the user to change the extent, zoom in and out, and go to the user’s location, we also added widgets with more functionality. For example, users are able to turn layers on and off, change the base map, add data layers to the map, download survey responses, print, and measure distances and areas.

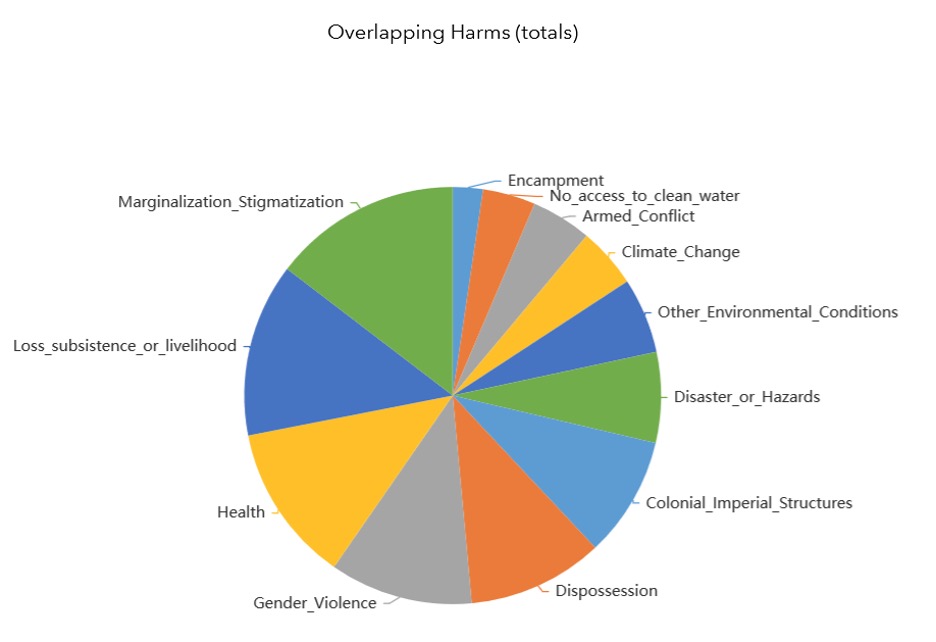

One of the most interesting widgets is the Filter widget, which we configured to enable users to filter data by twelve overlapping harms exacerbated by the pandemic, such as armed conflict, loss of subsistence, and gender violence, among others. Filtering by overlapping harms, illustrates the corresponding locations in the world where researchers and witnesses have identified the presence of harms intersecting with vulnerabilities associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. We know from the Filter widget, for example that armed conflict is presently reported on the map as an overlapping harm in five different locations spanning four continents, while gender violence is pervasive across all continents. Harms can also be summarized using the Chart widget, which generates pie and graph charts of overlapping conditions across all or a selection of the locations on the map. This widget reveals that across all entries, the greatest markers of intersecting harms due to the pandemic are stigmatization and loss of subsistence. The Information Summary widget offers a way for the user to view the submitted narratives, with the ability to click on the text to generate a pop-up for that entry at the corresponding location on the map. The widget enables us to present and highlight narrative information that is at the core of our research project.

With contributions from fourteen countries and six continents, this project has mobilized knowledge about vulnerabilities ranging from quality of the illegal drug supply and lack of access to adequate housing among residents of urban Vancouver, to overcrowding and lack of mobility among refugees in a camp in Chios, Greece. The narratives also highlight positive solidarities which have formed during the pandemic, such as the creation of local fishing cooperatives in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Esri’s suite of tools, from Survey123 to the customizable functions within web maps and Web AppBuilder, are typically used for collecting and analyzing highly structured, quantitative geographic data. We effectively adapted these tools to compile and visualize qualitative data about the complexities of intersecting inequities exposed and made worse by the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. ArcGIS Online provided a collaborative platform for multiple people within our network of field-based partners to work on different products at the same time, and we were able to take advantage of sophisticated tools like Arcade expressions and the various functionalities with Web AppBuilder to facilitate the sharing and analysis of important and timely narrative-based information.

A Call

We seek on-going collaborative dialogues and welcome colleagues from other continents to join the project team, to discuss results and new directions or possibilities for engagement. If you are interested in contributing to Ecologies of Harm, please email us and we will send you a Project Invitation with live links to the survey. If you wish to collaborate with us on the Extreme Weather Event survey, we will also be happy to hear from you.

Contact Email: Anth.CovidVulnerabilityMap@ubc.ca

Project Website: https://blogs.ubc.ca/ecologiesofharmproject/

Project Team:

Dr. Leslie Robertson, Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Maya Daurio, Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Stephen Chignell, Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Dr. Anita Lacey, Political Science, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Dr. Sally Babidge, Anthropology, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

[1] Project mappers Maya Daurio and Stephen Chignell were awarded the Esri Canada GIS Scholarship (2021) for their work with Ecologies of Harm.

Cited:

-

Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam. 2019. Editor’s Introduction: Urgent Anthropology: Gender, Ethnic Conflict, Migration, and Anti-Americanism. Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia 58(3): 117-122.

-

Bermant, Laia and Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov. 2020. Introduction: Urgent Anthropological COVID-19 Forum. Special Issue, Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 28(2):218-220.

-

Butler, Judith. 2016. Rethinking vulnerability and resistance. Vulnerability in Resistance, 12-27. Durham: Duke University.

-

Das, Veena. 2007. Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. Berkeley: University of California.

-

Ferrarese, Estelle. 2016. Vulnerability: a concept with which to undo the world as it is? Critical Horizons 17(2):149–59.

-

Farmer, Paul; Bruce Nizeye,Sara Stulac, Salmaan Keshavjee. 2006. Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine. PLoS Medicine 3(10): 1686-1691.

-

Fassin, Didier. 2013. Why Ethnography Matters: On Anthropology and its Publics. Cultural Anthropology 28(4):621-646.

-

Goff, Susan. 2001. Transforming Suppression-Process in Our Participatory Action Research Practice [64 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 21, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0101211.

-

Han, Clara. 2018. Precarity, precariousness, and vulnerability. Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 331-343.

-

Hepburn, Sharon. 2020. Pandemic vulnerabilities, mortality and empathy in fieldwork. COVID-19 Forum Special Issue Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 28(2): 280- 281.

-

Human Rights Watch. 2021. Canada: Disastrous Impact of Extreme Heat. October 5, 2021. Accessed October 9: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/10/05/canada-disastrous-impact-extreme-heat

-

Hundle, Anneeth Kaur. 2012. After Wisconsin: Registers of Sikh precarity in the alien-nation. Sikh Formations 8(3): 287-291.

-

Khalili, Laleh. 2011. The Ethics of Social Science Research, in Roger Heacock and Édouard Conte eds., Critical Research in the Social Sciences: A Transdisciplinary East-West Handbook, 65-82. Birzeit, Palestine: Ibrahim Abu-Lughod Institute of International Studies Birzeit University and the Institute for Social Anthropology, Austrian Academy of Sciences.

-

Kar, B., R. Sieber, M. Haklay, and R. Ghose. 2016. Public Participation GIS and Participatory GIS in the Era of GeoWeb. The Cartographic Journal 53: 296–299.

-

Marcus, George. 2005. The Anthropologist as Witness in Contemporary Regimes of Intervention. Cultural Politics 1 (1): 31-50.

-

Laura Nader. 2019. What’s urgent in anthropology, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9 (3): 680-686. (Original 1972).

-

Reed-Danahay, Deborah. 2016. Participating, Observing, Witnessing in, The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Anthropology. Routledge. Accessed on: 20 Aug 2019, https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315743950.ch3

-

Robertson, Leslie A., Maya Daurio, Stephen Chignell, Anita Lacey, Sally Babidge (2020) Ecologies of Harm: Mapping Contexts of Vulnerability in the Time of COVID-19. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. Project Website: https://blogs.ubc.ca/ecologiesofharmproject/

-

Sanford, Victoria and Asale Angel-Anjani Eds. 2006. Engaged Observer: Anthropology, Advocacy, and Activism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University.

-

Smita, Yadav. 2018. Introduction: Urgent Anthropology. In: Precarious Labour and Informal Economy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

-

Varma, Saiba. 2020. A pandemic is not a war: COVID‐19 urgent anthropological reflections. COVID-19 Forum Special Issue Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 28(2): 376- 378.

Cart

Search