An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Gender Based Violence TIG

Rethinking frontlines in a “post” Covid world

Rethinking frontlines in a “post” Covid world

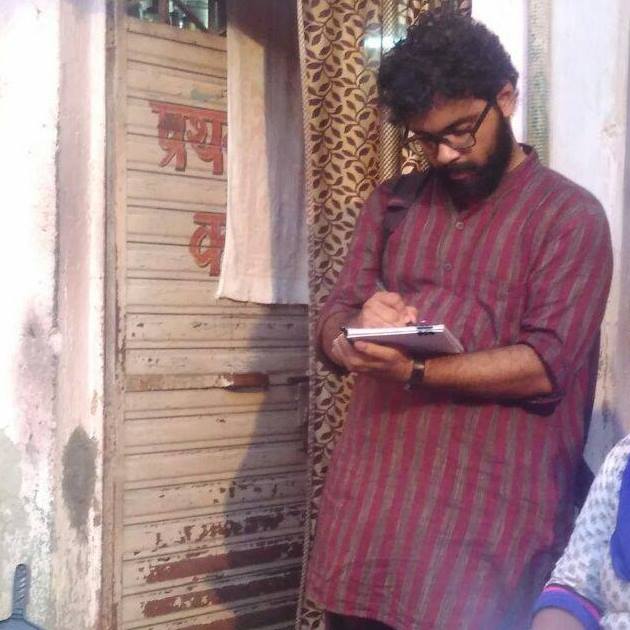

Proshant Chakraborty

School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg

proshant.chakraborty@gu.se

The Covid–19 pandemic has, by all means, upended our sense of space, time and sociality. Months of lockdowns and quarantines have deferred the present moment into a future of uncertainty, such that we are now imagining a post-pandemic world as one where we have to “live” with the virus as the “new normal.”

But were things really ever normal?

For billions worldwide, the pandemic has exposed deep, structural faultlines in our social systems and public infrastructures and institutions—which have been hollowed out by decades of neoliberal divestment. I am, of course, speaking from my location in India, where we currently have the second highest worldwide Covid–19 case count, despite (or rather, because of) having one of the “harshest lockdowns” in the world—which led hundreds of thousands of migrant laborers returning to their villages on foot, bicycles, or stowaways, and hundreds of deaths. I believe that my observations and inferences in this column hold true for readers in the U.S., as well as the rest of the world, infection surges have been worsened by the effects of neoliberalism, structural violence, exclusion, precarity, and fascism.

I am also speaking from a space of intellectual and emotional exhaustion. As much as I respect and admire the scholarship and commentary that have emerged following the pandemic—and indeed, we have much to learn—I cannot but help think of how deeply messed up it is for us to take recourse to academic or even public scholarship when the very means of engaging with the world have been so seriously compromised. This is particularly true for us anthropologists. Our mode of producing knowledge is so intricately tied to forming relationships with people, and now this very intimacy signifies the risk of infection and the threat of harm. Even then, many of the people and communities we work with continue to face these threats and risks.

This is certainly true for the people I have worked with over the last six years: women frontline workers. These women are engaged with an NGO’s violence prevention program in Mumbai’s urban poor neighborhoods. Frontline workers include both, community workers and volunteers, who intervene in instances of domestic and gender-based violence in their neighborhoods and communities. They provide care and support to survivors, raise awareness, and are vital to the NGO’s community mobilization efforts. Over the years, my work has largely focused on Dharavi, which is considered to be one of the largest slums in the world and, more recently, an exemplary “role model” of managing the pandemic.

Located in the centre of Mumbai, Dharavi is one of the largest urban poor neighborhoods in the city. Nearly a million inhabitants live in its socially, culturally and materially diverse neighborhoods (which also consist of thousands of migrant workers), and are engaged in its informal economy worth ₹1,500 crores (or $200 million) (SPARC & KRVIA 2010). Inhabitants of Dharavi also participate in the informal and service economy of the city at large—as clerks, civic employees, taxi drivers, domestic workers, sales staff, nurses, and so forth. Like other urban poor neighborhoods in the city, and the world over, Dharavi has largely been built through provisional and incremental improvements its inhabitants have made to their homes—building housing structures, as well as arranging for water, electricity, sewage, and roads. Much of Dharavi at present, then, consists of dense, materially sedimented neighborhoods and settlements (Weinstein 2014; Saglio-Yatzimirsky 2016).

So, when the first Covid–19 case was diagnosed in Dharavi in April 2020, things looked extremely worrying. However, even as infections increased over the next couple of months, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) mobilized resources, and with the collaboration of inhabitants, and managed to effectively test, trace, isolate and treat infections, which at present is over 3,150 identified cases (and under 200 active cases).

However, Dharavi’s success story in containing the coronavirus is only part of the picture.

Indeed, what made such measures possible was a suspension of the socialities and solidarities of everyday life—the provisional, open-ended transactions and interactions between residents—which make the urban space inhabitable in the first place (Bhan et al. 2020). While many in Dharavi and elsewhere talk about the loss of employment (rozgaar), one of the critical effects of the pandemic and the political economy of lockdowns was how it has constrained everyday acts of care, support and solidarity that residents provided to each other. Similarly, despite the efforts of local NGOs and philanthropic organizations to provide food relief to inhabitants, not only did hundreds of thousands of families have to deal with insecurity, vulnerability and stigma, but many also were unable to “make do” through forms of support that were normally available to them. This is also a gendered problem, considering how women and girls’ socially reproductive care labor is central to maintaining domestic and public spheres, which was exacerbated during the lockdowns and led to increasing instances of domestic and intimate violence. These cases of violence also constrain the ability and opportunity for frontline workers to intervene and support survivors and provide access to the justice system.

What is a unique about the pandemic, then, is how it has exacerbated existing and entrenched vulnerabilities, and constrained the existing modes of support that were available to urban inhabitants (Bhan et al. 2020). Even before the pandemic, my collaborators were able to work with communities, women and children in such political economic conditions, and engender change and transformation in their lives whilst navigating ever-present precarity and violence.

Even as it is difficult to think of the future of frontline work “post” COVID–19, I wish to take the remainder of this column to rethink our past, collective knowledges, and indeed the import of the term “frontline” itself.

In the early days of the pandemic—what, to me, now seems an eternity ago—there were many discussions on social media and in policy circles about the importance of “essential” and “frontline” workers, referring to nurses, paramedics, health workers, and even grocery workers. Many commentators, including nurses and medical practitioners themselves, critiqued such analogies, primarily because the term’s connotations of war and conflict suggest the suspension of civil liberties and institutional frameworks that are an essential part of public health responses. It was around this time (April 2020), for instance, that U.S. President Donald Trump was fashioning himself as a “war-time president.” In India, over-burdened and underpaid healthcare workers were celebrated as “Covid yodhas” (warriors), even as basic safety measures like PPE kits were in short supply, and were administered unproven prophylactic treatments like hydroxychloroquine or HCQ (also aggressively advocated by Trump).

Yet, over the years I have come to see both the utility and critical relevance of the term “frontline,” especially as it describes the embodied and affective labors of care, support, and solidarity. In doing so, I am indebted to the wisdom and knowledge I have inherited from feminist anthropologists and scholars like Jennifer Wies and Hillary Haldane, who have co-founded this TIG and edited the volume, Anthropology at the Front Lines of Gender-Based Violence(Wies & Haldane 2011b), a definitive text that has contributed to the scholarship on frontline workers in the field of violence prevention.

Wies, Haldane, and the contributors of the volume draw on rich, engaged, feminist and applied anthropological scholarship to generate new perspectives of studying gender-based violence (including that of Madeline Adelman and the late Sally Engle Merry, from whom they use the term “frontline”). More importantly, the contributors focus their attention on frontline workers, who Wies and Haldane describe as “barometers of violence” who can “map the scope and scale of violence in their communities,” and “understanding their stories is a necessary part of any effective effort to end the global pandemic of gender-based violence” (Wies & Haldane 2011a, 2, my emphasis).

In these trying times, I have found myself drawing upon the scholarship of the contributors of Wies and Haldane’s volume and my fieldwork. I have pored over old fieldnotes and code indexes, finding patterns and insights that I was intuitively aware of, but was only now able to articulate clearly. I realized how closely my frontline worker colleagues’ ideas and experiences were tied to the foundational understanding of frontline work/ers expressed in Anthropology at the Front Lines of Gender-Based Violence. Most crucially, I believe that such discussions serve to decenter the militaristic underpinnings of the word “frontline” (which was rightly been criticized).

Carolyn Nordstrom’s (2004) study of violence and conflict is instructive here. Tracking multiple conflicts over multiple countries and time periods, she argues that the “frontlines” of violence are not discrete spaces where the violence takes place. Instead, conflict and violence extend worldwide, through networks of politics and profiteering, and are the result of global power relations. Nordstrom further argues that in the larger narratives of violence and peace (or, “war stories”), daily realities of the frontlines are erased. She writes, “Serious and representative stories of front-line realities do not circulate in the media and literature worldwide. But in all too many, the central actors and central victims fall out of the telling” (2004, 31–32).

We thus see that even in contexts of global violence, frontlines actually represent how spaces and actors involved in the thick of violence are obscured and invisiblized, not unlike how intimate experiences of violence (and the burden of care) are invisiblized in popular narratives on spaces like Dharavi. In a recent article, I built on the scholarship on frontlines and GBV to show how logics and ethics of care are central to frontline workers everyday negotiations, how this blurs public–private boundaries, and how socially reproductive care undergirds the material and affective economies of urban life (Chakraborty 2020). However, as much as the pandemic has upended and undermined such negotiations, we must remember that frontline workers were, and always are, part of a deeply unequal world. There are material, social and political limits to care. It is problematic to valorize such labor, whether or not we in a global pandemic, precisely because doing so obscures the violence and inequities that frontline workers’ face and respond to. As we look to their efforts, we have the responsibility to ask questions regarding the erosion of political accountability and breakdown of infrastructures and institutions.

If we understand frontlines as a metaphor or heuristic for sites and relations of struggles, as I believe we should, then this is precisely from where we must ask critical questions and foreground our ethical and political commitments. In an important way, frontlines help us open up questions of investigation and arenas for social and political mobilization. It is from the frontlines that we can speak truth to a particular, global exercise of power and contribute to contemporary social movements for health, justice, and equity. In so doing, we can upend the potentially inequitable and exclusionary logics of belonging which privilege abstract, universal values in interventions, policy, and healthcare. Instead, we can direct our efforts and collaborations with local actors, emphasising plural narratives and solutions to the problems of violence and inequity. That is the promise of frontlines.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Emma Backe for this opportunity to contribute to the SfAA newsletter, as well as for her encouragement and comments. I am thankful to Hillary Haldane for the numerous conversations we’ve had on frontlines and frontline workers over the years. Finally, I am indebted to my frontline worker colleagues and collaborators in Dharavi and elsewhere, for their patience, kindness, wisdom and inspiration. The views expressed and errors are my own.

Works cited

Bhan, Gautam, Teresa Caldeira, Kelly Gillespie, and AbdouMaliq Simone. 2020. “The Pandemic, Southern Urbanisms, and Collective Life.” Society and Space Magazine (August 3). https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/the-pandemic-southern-urbanisms-and-collective-life.

Chakraborty, Proshant. 2020. “Gendered Violence, Frontline Workers, and Intersections of Space, Care and Agency in Dharavi, India.” Gender, Place and Culture (March 31). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1739004.

Nordstrom, Carolyn. 2004. Shadows of War: Violence, Power, and International Profiteering in the Twenty-First Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Saglio-Yatzimirsky, Marie-Caroline. 2016. Dharavi: From Mega Slum to Urban Paradigm. New Delhi: Routledge.

Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centers, and Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture. 2010. Reinterpreting, Reimagining, Redeveloping Dharavi.

Weinstein, Liza. 2014. The Durable Slum: Dharavi and the Right to Stay Put in Globalizing Mumbai. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Wies, Jennifer R., and Hillary J. Haldane. 2011a. “Chapter 1: Ethnographic Notes from the Front-Lines of Gender-Based Violence.” In Anthropology at the Front-Lines of Gender-Based Violence, edited by Jennifer R. Wies and Hillary J. Haldane, 1–20. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Wies, Jennifer R., and Hillary J. Haldane. Eds. 2011b. Anthropology at the Front-Lines of Gender-Based Violence. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Proshant Chakraborty is an applied anthropologist and independent consultant based in Mumbai, India. He obtained his B.A. in Sociology and Anthropology from St Xavier’s College, Mumbai, in 2013, and his MSc. in Social and Cultural Anthropology from KU Leuven, Belgium, in 2016. Proshant has had field research experience in public health, AIDS advocacy and interventions, urban ecology and environment, migration and labor, prevention of violence against women and girls, and community-based participatory research. Since 2014, he has worked extensively with frontline workers in Dharavi, and his individual and collaborative research has been published in Violence Against Women, Men and Masculinities, and Gender, Place and Culture. He has been part of the SfAA Topical Interest Group on GBV since 2016. He is currently a doctoral candidate in Social Anthropology at the School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg.

For more information on the Gender Based Violence Topical Interest Group or to join our listserv, please drop us an e-mail at gbvanth@gmail.com.

Cart

Search