An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Oral History Interview with Donald D. Stull

A Career Path Leading to Application in Agriculture: A SfAA Oral History Interview with Donald D. Stull

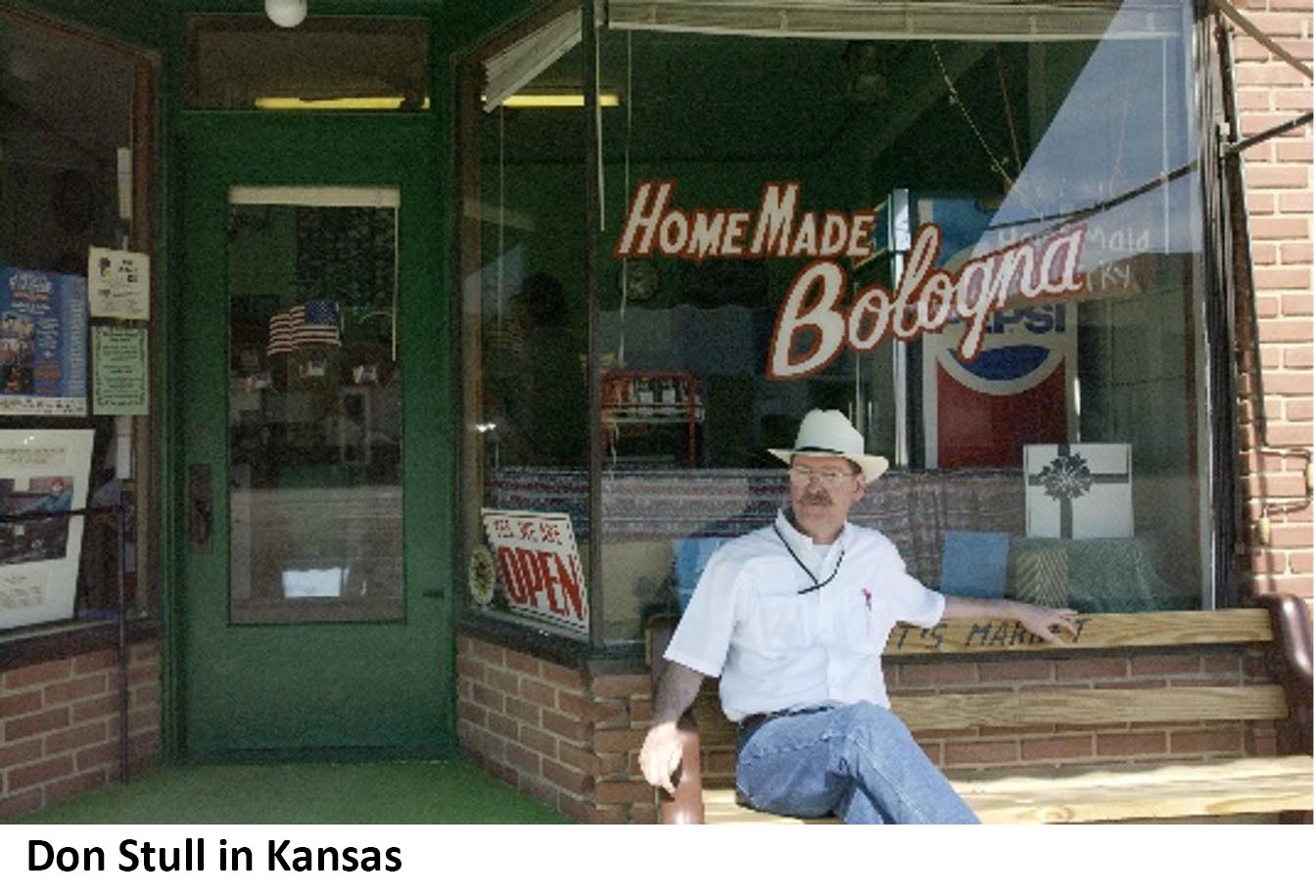

Donald D. Stull is Professor Emeritus at the University of Kansas. He served the Society in a number of ways including as president from 2007 to 2009 and as the editor of Human Organization from 1999 to 2004. The Society recognized his contributions with the Sol Tax Distinguished Service Award in 2009. His research has produced important studies of the meat and poultry industries in United States. Don has also studied the impact of changes in the federal program of market controls of burley tobacco production. Since retiring in 2015, Don splits his time between Lawrence, Kansas, and Sebree, Kentucky. John van Willigen was the interviewer and edited the transcript. The interview was done in Lexington, Kentucky.

Donald D. Stull is Professor Emeritus at the University of Kansas. He served the Society in a number of ways including as president from 2007 to 2009 and as the editor of Human Organization from 1999 to 2004. The Society recognized his contributions with the Sol Tax Distinguished Service Award in 2009. His research has produced important studies of the meat and poultry industries in United States. Don has also studied the impact of changes in the federal program of market controls of burley tobacco production. Since retiring in 2015, Don splits his time between Lawrence, Kansas, and Sebree, Kentucky. John van Willigen was the interviewer and edited the transcript. The interview was done in Lexington, Kentucky.

VAN WILLIGEN: It is November 4th, 2005. I'm John van Willigen. I'm talking to Don Stull for the Society for Applied Anthropology Oral History Project. Don, you're from western Kentucky. Were you actually born in western Kentucky?

STULL: I was born in western Kentucky in Sebree, which is about halfway between Henderson and Madisonville. But my parents moved to Texas when I was three. And I came back to Kentucky every summer on my grandparents' farms, and then came back to the University of Kentucky as an undergraduate. So, Kentucky has this mythical place in my life. And I've continued to come back to it over and over again.

VAN WILLIGEN: Did you major in anthropology right away?

STULL: I came [to the University of Kentucky] in 1964 as a freshman. Three people entered in anthropology when I was a freshman and eight people graduated four years later in 1968. To my knowledge I'm the only one that became a professional anthropologist. Doug Schwartz was my initial adviser. He left to go to the School for American Research [about a year later]. The people that were here [included] Frank Essene. I took my introduction to cultural anthropology from him, and Margaret Lantis was here. I took American Indians from Margaret. I took introduction to physical from Louise Robbins. I took South American Indians from Tom Weaver. I took applied anthropology from Art Gallaher.

VAN WILLIGEN: Could you tell me about--

STULL: And we used Homer Barnett's, Innovation and Culture Change. There were probably about twenty, twenty-five students in that class. It was a hard class. (laughs) I got a C. (laughs) And I worked (hard to) earn that C. I like to tell my students now when I give them a B, or a C and they are terribly upset that it's the only course I ever took in applied anthropology and I got a C. And I'm damn proud of it.

STULL: Henry Dobyns was the chair. And his classic work on the aboriginal population of the New World came out in Current Anthropology when I was a student here. Albert Bacdayan was also on the faculty here. He offered the senior tutorial; I don't know if you all still do it but there was a senior tutorial. It was a seminar. We all had to take it and it was a different topic. We all had to take it and it was on Appalachia. Of course, that was when Appalachia was the War on Poverty and it was getting a lot of attention and Albert, I don't think knew anything about Appalachia, but we explored it together. And Night Comes to the Cumberland had come out fairly recently and actually I thought seriously about specializing in Appalachia, but I got into anthropology because of an interest in (American) Indians and I continued that. When it came time for me to go to graduate school and was accepted to University of Kentucky. I was accepted to the University of Montana. It had a master's program to train people to work at the BIA. And Colorado. I'd also been accepted at Nebraska, and I was wanting to do Indian stuff and trying to get out west where I could do it. And I told Art where I'd applied. And he advised me not to go to Nebraska or to Montana. And, you know, he's always been immensely supportive of me. And I've always been terribly grateful because here was this, you know, undergraduate who took one class who got a C and he took an interest nevertheless and has continued to take an interest in my career long after I left Kentucky. I think I got into applied in part because of the people that were here at that time. People weren't wearing applied on their sleeves, but you had Tom Weaver, you had Art Gallaher. You had Hank Dobyns. Marion Pearsall was here. Human Organization was being edited here at that time. And one of my most vivid memories was I was working as a student hourly at the department on different things. And we got told we could go into the stacks where back issues of Human Organization were housed and take the top copies which were dusty, that they couldn't really send out. And I went in there and got all these issues. not every back issue, but a bunch of them going back even to when it was calledApplied Anthropology. It was just this magical thing.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, there wasn't a very strong applied focus at that point.

STULL: Yes and no, I sort of thought of anthropology like social work. I thought if you don't do something with it what good is it? When I was a senior Rich Stoffle came from Colorado. He was an undergraduate at CU. And he came and was a graduate student in my senior year. And he went on to be I believe, correct me if I'm wrong, the first doctoral student.

VAN WILLIGEN: That's the way I always thought of it.

STULL: And he came (to Kentucky) to be in applied anthropology. He and I had some interesting discussions because he said, "What do you want to go to Colorado for? You know, that's a physical program." And it was known for its physical anthropology then. But I went to Colorado in the fall of 1968 to study under Omer Stewart and John Greenway. Both of them were gone that year on sabbaticals. I ended up studying under other people. At the same time, you know, Kentucky was--well, at that time Human Organization was edited by Marion Pearsall here. Tom Weaver, past president of SfAA. Art Gallaher, also Hank Dobyns. It was clearly a place where applied anthropology was just part of anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And there wasn't that kind of tension or a battle back and forth about whether applied is real anthropology, whether it's legitimate or not.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right. Right.

STULL: And then I went to Colorado in 1968. Albert Bacdayan was friends with Del Jones. And when I was looking for somebody to connect with. Albert said, "Well, I've got this friend Del Jones [Delmos J. Jones] and why don't you look him up when you get there?" And he was at Colorado. He went later to City University. But I went, there was a reception for the incoming graduate students at the student union. Albert didn't tell me that Del was black. And then I was a Southern boy, and I was really pretty--I mean I came out of the South, and I walked up and there was this tall, handsome, impressive African American.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: I introduced myself, he was my adviser, and we had a wonderful relationship. But I can remember I mean just sort of, it was for me a shock and really, I came to anthropology being fascinated with American Indians, wanting to work with them, but also coming out of a background that was very was traditionally Southern and I had grown up in segregated areas. I don't want to say that I've become Mother Teresa, but it really transformed, was a transformative experience for me.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, what was it like working with Del Jones?

STULL: I got there in '68. I didn't have funding. I drove a school bus and sold Cutco knives for a semester. And the only people that bought my knives were my relatives. Del had a NIH program in doing health research in the slums of Denver. And in housing projects in Denver. I hired on with him and did some research in Denver. We would meet once a week and with his students and have seminars. Oscar Lewis's culture of poverty was a big deal then. And we were looking [at those] issues. Is there a culture of poverty and if so, what is it like in places like the Denver (housing projects)? And then Del went after a year to City University. And we continued to remain in contact until his death.

VAN WILLIGEN: That's about a decade ago now.

STULL: Yes, I guess it is.

VAN WILLIGEN: He too worked with the Papago (Tohono O’odham).

STULL: He did and there is that Papago connection.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And Bob Hackenberg had come [to Colorado] from [University of] Arizona, Bureau of Ethnic Research, it's Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology now.

VAN WILLIGEN: I was a research assistant at the Bureau of Ethnic Research.

STULL: And so, Bob had come there a year or two before me. And Del had been Bob's student at Arizona. He had gotten his master's with Bob. And so, when Del was leaving, and I was looking for somebody else. Bob had NIMH, predoctoral, fellowships. They were good for four years and I camped out on his doorstep until he gave me one, I mean basically. (laughs)

VAN WILLIGEN: What was the structure of that? I mean was it open-ended? Or did you have to work on a certain set of projects.

STULL: It was sort of open-ended but most of us worked on Papago material.

VAN WILLIGEN: It's in that time period where you chose the South Tucson Papago.

STULL: There was one of the requirements of that, it was a four-year fellowship. There were no requirements other than, we had to do a once-a-week seminar with Hackenberg. It met one evening a week in the basement of IBS, Institute for Behavioral Sciences, which was an old three-story building on Broadway Street. He got all of his students together one night and said, "We're going to do a symposium at some meetings in Tucson." It was Southwest Anthropological Association meeting I believe. "And you're all going to pick a topic. It's going to be on the Papago." He had the Papago Population Register, which was a precomputerized data bank. At that time, we were doing punch cards. And he had about, I don't know, a dozen or so topics.

VAN WILLIGEN: I actually was a coauthor of a paper that was a Papago Register paper.

STULL: Oh, really?

VAN WILLIGEN: With Harland Padfield. The labor survey.

STULL: Sure, of course. So, he had about, I don't know, a dozen topics. There were about six or seven other students. And we all picked one.

VAN WILLIGEN: Who were some of the students?

STULL: Kerry Feldman, who's now at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He went there right out of school and has really built anthropology at Anchorage. Mary Gallagher (at) Montgomery County Community College. David Glenn Smith, who was a graduate of UK. David is a population geneticist. And he was a year behind me at Kentucky. He followed me to Colorado. He's been out in California ever since. David Zimmerly, he was an ethnographer in Canada. Those are the ones that come quickly to mind.

VAN WILLIGEN: Did you at that point, thinking of that milieu, I have this idea of Hackenberg and his worldview within anthropology. Was application an important theme in your thinking about yourself at that point?

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: What was the thing that attracted you or pushed you with that idea about yourself?

STULL: Well, it was the late 1960s, and the whole country was in that sort of milieu in which we existed. For me a concern with contemporary Indians although what got me interested was nineteenth century Indians. But I wanted to be of use to American Indians. We were very much in--I started to say indoctrinated. I don't mean it quite that way but an underlying theme throughout all of our discussions was that anthropology should be useful, that it should be problem-focused, and that we should be, our research should be useful not only to the discipline but to the people that we were studying. We didn't talk much about practice, that wasn't a discussion at that time.

VAN WILLIGEN: Was there a big consciousness about here's applied anthropology and here's nonapplied anthropology?

STULL: No. Not at Colorado and not at Kentucky.

VAN WILLIGEN: I never even sensed it at Arizona actually, when I was there.

STULL: You know, we didn't, there wasn't that divide. I mean it was well, of course anthropology is going to be applied, why else would you do it. There was certainly a trend toward quantification. Toward making it more scientific. We didn't talk much about culture. When we did, we sort of looked down our noses at culture. We were spending a lot of time reading things that debunked functionalism and that kind of thing.

VAN WILLIGEN: What were some of the more clearly theoretical things that were part of your [reading]. You mentioned earlier playing off with this culture of poverty idea.

STULL: We were looking at that and Charles Valentine's critique was certainly something that we were reading very carefully. And we were reading Oscar Lewis, but we weren't reading that without also balancing that with Valentine. We were reading people like Samuel Stouffer.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

STULL: We had the register. We were doing things, and I chose accidental injury as my topic.

VAN WILLIGEN: That would have been important.

STULL: It was at that time the leading cause of death among American Indians.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. I recall this from the work I did with Harland. It was in certain age-gender cohorts, it was devastating. Males in their twenties is what I remember. It was just like that's the way they died basically.

STULL: That's the way they died. And, of course, there was this wonderful quantitative database and so we all picked our topics. We all used the population register to write our papers. Then the meetings were in Tucson. None of us had ever seen a Papago.

[Pause in recording.]

STULL: It was with Bob Hackenberg. Bob had told his students to select these topics.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, I see, so it's still dealing with the register.

STULL: Yeah. And we were told to write these papers from the population register. So, we did. We submitted our session to the Southwest Anthropological Association meetings in Tucson. And we all, my parents had bought me a 1968 Chevy Nova for graduation. And it was the newest car of all of our group. So, we all piled into this Chevy, and we drove down to Tucson and delivered our papers. There were more people on our panel than there were in the audience. And on the way and that's where we saw our first Papago. We had all written these papers about the Papago talking about all these things like we knew what we were talking about. None of us had ever seen one. So, we went out there and saw them. We came back.

VAN WILLIGEN: Did you go out to the reservation at Sells or San Xavier.

STULL: We went to San Xavier.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

STULL: Well, nobody had gone to hear our papers. So, the next year we submitted them to AAA. We changed the titles, and we gave the exact same papers. And why not? No one had heard them to begin with, although I wouldn't advise people to do that now. But we thought it was okay.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: We began looking for dissertation topics. And my paper had proposed the notion that there was a positive relationship between levels of accidental injury among the Papago and modernization. There was this disjuncture because people raised in traditional backgrounds and confronted with modernization--that accidental injury was an indicator of stress basically.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: It all sounded very good and there was this notion that there was community modernization because all of the villages on Papago had been rated on a modernization scale and individual modernization. I'm a Catholic, I'm a veteran, or all these things. And so, it appeared to be that if you were a modern individual in a traditional community, you were at higher risk. Or if you were a traditional individual in a modern community, you were at higher risk. And so, I went back to look at that for my dissertation. I was supposed to go to the reservation, but the tribal chairman Tommy Segundo was killed in a plane crash--

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh yes.

STULL: --shortly before I was supposed to go. And of course, I had to get permission from the tribal council to go on the reservation and that wasn't high on their list. So, after a few months I said, "Well, I can do this in Tucson." Because South Tucson was one of the fifty some, Papago communities that was ranked in terms of modernization. And so, I went there and did my research there. By that time Bob and Julie Uhlmann, who was also one of Hackenberg's students, one of his group, was there at the same time. She was doing research in Tucson, also building on the paper that she had done. But I was the last of the Hackenberg students to do research on the Papago. And he by then was already doing his research in the Philippines in Davao City on Mindanao and was there when I did my research in Papago and when I wrote my dissertation. So, he was gone. Friedl Lang filled in for him.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, your dissertation director is Friedl Lang.

STULL: Yes, that's right. And it was on accidental injury and alcohol use among the Papago in Tucson.

VAN WILLIGEN: Who else was on your committee, Deward?

STULL: Deward Walker, Omer Stewart, Friedl, Gordon Hewes.

VAN WILLIGEN: I've heard of Gordon Hewes. Didn't know Omer very well. But I've met him.

STULL: He was a wonderful man. I never took a course from him, but he was great. He always wore a very distinguished full head of white hair. Wonderful mustache always wore a gray suit with a peyote button for a lapel pin and usually a bolo tie.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right, right.

STULL: Boy, the stories about him were something else. But he was a wonderful man.

VAN WILLIGEN: I met him, I think it was at an AAA meeting in Denver. And I went to a party, and he was there.

STULL: (laughs) Yes, he was notorious for that. But, you know, I went to Colorado to study under Greenway, who was a folklorist. And Omer, I wanted to specialize in Native American Church.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And they were both gone when I got there and then I met Del and got funding and essentially, I gravitated into the Papago because that's where the money was. I did a census of the Tucson Papago asking--sort of had a standard questionnaire. And then from that I selected a sample of individuals to interview about alcohol use and other things. And what I found was that the Papago were heavy drinkers.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And at that time the prevailing theory was that Indians drink because of acculturation stress. Their traditional way of life has been taken away from them.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: They haven't been admitted into the mainstream American culture. So, they drink because they're under acculturation stress. And that was the prevailing theory. Dick Jessor was a leading alcohol researcher at Colorado then. Sociologist. And that was what people thought. There had been very few studies of alcohol use per se. People, anthropologists usually wrote about alcohol as an aside.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: They had gone to study reservation Indians.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: And then, you know, Indians drink. And so, when they were up for tenure or had nothing better to do, they wrote an article about Indian drinking. And it usually said Indians drink because they're stressed. And that was the theory that I tested and, of course if you're looking for that, you find it. By the time I got back and really was immersing myself in the literature I realized that there were these other competing theories. For example, MacAndrew and Edgerton. Drunken Comportment, that said basically that, or Jerrold Levy and his studies of Navajo drinking that American Indians learn to drink from Anglos and they learn to drink from explosive drinkers, missionaries. Missionaries saying either, you know, you don't drink, so there's this prohibitionist notion.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

STULL: And then you have soldiers and trappers and cowboys and anthropologists who drink explosively. So, it's either you don't drink, or if you do drink, you drink explosively. And the MacAndrew and Edgerton piece convinced me that this notion of acculturational stress was, was just a bunch of malarkey. My data showed that the Papago drank tremendously. They also were of course one of the few groups that had alcohol before Europeans came. And I decided, I’m not very confident in it. And I had a few pieces that I could publish, one of which you kindly reviewed for Urban Anthropology. And I said, "I'm just not going to--I just don't want to write about that." And so, I didn't write about it and--because I didn't think the data were worth--I got three articles out of my dissertation. I thought that was plenty. And I was confident in those articles. The drinking stuff I never published. I didn't think it had validity by the time I began to really come to grips with it. And I still don't. I abandoned the drinking part of it. And I published on accidental injury. And on the modernization aspects. Then I got my degree in '73. When I entered Colorado in 1968 the people that were graduating, the graduate students that were getting their PhDs, were getting four and five job offers. When I came out in '73 I got four interviews, and no job offers.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. I started my first job in '70. And my degree was in the middle of the first year of work, and so it was '71.

STULL: Yeah. I was desperate, by then I was married and had a child. I went down to the Boulder County Employment Office and applied for unemployment and looked at the jobs. And there was a job advertised by the American Humane Association. The dog and cat people.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: And they were looking for someone to be the associate director of the National Clearinghouse on Child Neglect and Abuse. The very first child abuse case in America was tried under animal protection laws in the 1870s.

VAN WILLIGEN: Wow. So, you took this job.

STULL: And it was called the Mary Ellen case. And there were laws passed in the 1870s to protect draft animals from abuse, you know horses pulling carts and stuff. And some girl had been chained to her bed in the attic by her evil stepparents and had been found and so they tried these people under animal protection laws and prosecuted them. So there had been SPCA, Societies for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and then there--

[Pause in recording.]

STULL: So, child abuse was just--this was in 1974. And child abuse was just appearing on the national consciousness. The American Humane Association in Denver was a leading mover and shaker in child abuse and at that time there were laws in the various states. But there wasn't a standard definition of child abuse or neglect. There wasn't a standard data collection system.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: And so, I was hired as the associate director of the National Clearinghouse on Child Neglect and Abuse. It was in Denver. And to set up a standardized reporting form.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. And your quantitative skills--

STULL: I really was hired not as an anthropologist but as someone who was able to develop a -quantitative data collection system. We did all this stuff for months trying to figure out how to do this reporting system. Called together the social welfare offices from all fifty states, had conferences. And I developed the standardized reporting form, which was then put in practice and--but I wanted to be at a university.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: I wasn't really happy where I was. I worked for a lawyer who really was a big name in child abuse. And of course, the dog and cat people were there. The child abuse people were sort of second-string. I was in this office, had this beautiful picture window of the Rockies. Every day I would watch the Rockies disappear in the smog. The director of the Humane Association was an alcoholic. He would wander in. The refrigerator was in my office. And he would get his vodka and drink it. And I had to wear a coat and tie every day. I had to keep my door open. I couldn't put my feet up on my desk. If I had nothing to do, I couldn't go home. I had to stay there from 8:00 to 5:00. I had to take scheduled coffee breaks. Here's this, you know, bearded long-haired anthropologist saying, "What the hell am I doing in this place? And really I'm interested in Indian drinking." So, I, uh, and at that time practicing anthropology was not on the radar screen.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: I went to the AAA meetings that year. I don't remember where they were. But I ran into Bill Adams. And we sat and had a nice chat and I told him what I was doing. And I described it as applied anthropology and he said, "No, it's not applied anthropology. It's not anthropology." Now I'm not criticizing Bill for that but that's what we thought in anthropology, that doing that kind of thing, which today we would consider practicing anthropology, and we would all think is a wonderful thing, then it wasn't considered anthropology. It was something else, but it wasn't anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And I sort of believed that too.

VAN WILLIGEN: You felt outside the discipline.

STULL: I was. I was disconnected. I mean I was still maintaining personal ties. I'm just not doing anthropology. So, I looked around and I found a postdoc at the social research group in the School of Public Health at Berkeley at the University of California Berkeley. They'd just established a postdoctoral program. They were the group that was doing most of the alcohol and drug studies in the United States. They were almost all sociologists, some social psychologists. I applied for the postdoc. They gave it to me. I was their very first anthropologist that they had. Their first postdoc. And so, I did a year, uh, in Berkeley.

VAN WILLIGEN: And that's when you got your MPH.

STULL: That's when I got my MPH because I got there. They didn't know what to do with me. They didn't know what to do with an anthropologist. And so, they said, "Well, you can take an MPH and not have to pay anything." I said, "Well, great." And so, I wrote a couple articles, you know, while I was there. But did the MPH. And then I applied for academic positions. I applied for the Kansas position. And then I was asleep, and I got a call from Kansas--woke me up, you know, it was like 6:30 or something my time, it was two hours later in Kansas--offering me the job in Kansas. I couldn't--at first, I didn't, you know, I haven't interviewed, I mean you call me up out of the blue and offer me this job. And so, I took it.

VAN WILLIGEN: You didn't--you weren't really interviewed?

STULL: No, Kansas. I jumped. I applied for the one-year visiting appointment. Why would they bother to bring somebody from California? They were just going to be for a year, so what the hell?

VAN WILLIGEN: So, at this point when you go to Kansas you didn't necessarily have an identity as an applied anthropologist.

STULL: No. I was hired as a medical anthropologist. When I began looking for jobs when I was writing my dissertation. And at that time, you still got interviewed in motel rooms at AAA.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: You know, they didn't have the booths and the very the cattle call kind of thing.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: You would get invited up to a motel room. There'd be drinks and you would have a conversation. And the questions would be, you know, do you see yourself as a researcher or teacher, and that kind of thing.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: But they would also try to pigeonhole you. And people began telling me I was a medical anthropologist because I was doing research on accidental injury and alcohol use and stuff. I said, "Well, I guess I must be." So, I began marketing myself as that. And the job at Kansas was for a medical anthropologist. So, one of the attractions of Berkeley was that I could get an MPH and I could then legitimize myself. I have a degree in public health.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

STULL: And that made me a medical anthropologist. And that's what I was hired to do at Kansas. But I mean I've always been sort of an opportunist. I go where the money is and applied anthropology was a dirty word at Kansas when I came. And that was the first place that I had encountered--I mean at Berkeley I was in the public health. I went to lectures at anthropology and visited with people, had lunch with George Foster. But I wasn't really part of the anthropology world. I was in the public health school.

VAN WILLIGEN: --and at Kansas?

STULL: At Kansas there was this very rigid division between anthropology and applied anthropology. It went back to Vietnam. It was a very marked division. Even though Akira Yamamoto who was there when I came--he's an applied linguist, a leading figure in revival and maintenance of Native American languages, and he was doing applied linguistics. That's really when I began to label myself as an applied anthropologist. Although I'd always thought of myself in that way, I guess but it wasn't quite so important to wear that badge before. You know, Saigon fell in April of 1975. I mean it was just the end. And there was all of the--end of the war. And there was--applied anthropology was identified with the war effort, at least at KU.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: For better or worse and I got there, and I started doing work with American Indians. There are four tribes--federally recognized tribes in Kansas. And I started working with them to do censuses and things like that that were of use to the tribes. I always thought that my research should be of use. And I began to seriously read Sol Tax's work on action anthropology and Steve and Jay Schensul were publishing on what they were calling action anthropology in Chicago at that time in Human Organization. They had brief articles; communications I think they were called. And they were talking about applied anthropology--or action anthropology in Chicago. And I began to read that and then began to read Sol Tax and began to say, "You know anthropology should be useful to the people that we're studying."

VAN WILLIGEN: So. there was always this view.

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: Starting at the very, very beginning--

STULL: --yes, it was part of anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: Somehow it should be useful.

STULL: And so, I always felt that anthropology should be useful. Otherwise, why bother? At Kentucky and at Colorado we didn't even talk about that stuff.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right, right.

STULL: It was just accepted.

VAN WILLIGEN: But somehow at KU.

STULL: At KU we weren't shooting each other but it was that demarcation for sure. John Janzen was there. The leading figure in medical. Allan Hanson, he's well known for the reinvention of tradition, a specialist in Māori, and Dorothy Willner was there. Felix Moos identified as an applied anthropologist, the only one who had validly said, "I am an applied anthropologist." And he had been vocal in his support of the Vietnam War. I mean I don't think. I know it did. And it's unfortunate that it did. There's not a single cultural anthropologist at Kansas that has not done applied research. At this point. And some of them won't. John Janzen, Allan Hanson would never call themselves applied anthropologists. But they do wonderful work. I mean John's work with Rwandan refugees.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: Allan Hanson is doing all this stuff with testing in contemporary America and so their view now is much different. But we would still never be able to, I think, pull off a formal applied program.

VAN WILLIGEN: That's really quite interesting because these issues that you're talking about pervasively influence attitudes across the discipline.

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: I mean, you know, it's kind of pocketed out, so some places there, there isn't this opposition. In other places there, there is. But in the discipline as a whole, it's my view that this was going on. Had something to do with the Vietnam experience and as these people age and retire and it's become less intensely held. And self-limiting but was really hard on people who were in that age cohort and were applied because they were they were looked down on chronically you might say.

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: They follow their own strategies. Well, this doesn't sound nuts.

STULL: And we would never dream of hiring a cultural anthropologist now who didn't have an applied interest. They might not call themselves an applied anthropologist, but they've got to have that.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, your applied interest started to get focused around action anthropology.

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: And then did you ever think of the idea of action research? Was that part of it?

STULL: Well, not what we call action research today.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. Okay.

STULL: I should also say that people at Kansas were always supportive of my work. I mean they never--I did a lot of pretty chancy things as an untenured professor.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: And, looking back it was probably pretty foolish. For example, I contracted with the Kickapoo Tribe and wrote a book, a tribal studies text, that was published by the tribe.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: It was part of this action anthropology approach. And I was always given full credit for it. I mean they never said, "Well, that's not real anthropology." So, part of it was just issues of personality too. If people liked you then they were less inclined to say, "Well applied anthropology is not a good thing."

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. So, some of the influences were Sol Tax s--

STULL: --Sol Tax, the Schensuls, Vicos were probably the big influences on me. I mean my teachers like Gallaher and Dobyns and all those people. But the other people I was reading.

VAN WILLIGEN: I think I said to you that this collaborative anthropology book deserves to be reprinted.

STULL: Well, you're very kind. I wish it would be.

VAN WILLIGEN: Because it’s really useful. There isn't that much material on this and then that Westview.

STULL: Westview, they sold the stuff to libraries and then they dropped it. [That] was my interpretation of what they did. I think there are some very good pieces in there and I'm very sorry it's not still in print.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, it's hard to get ahold of it.

STULL: You know, there were various people in that period in the early 1980s that were reinventing action anthropology. Karl Schlesier at Wichita State.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh yeah.

STULL: He wrote that "Action Anthropology among the Southern Cheyenne," a wonderful piece.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, it's very interesting.

STULL: I don't know if Karl is still alive or not. He retired a number of years ago. He was an archeologist. And Wichita State is not a real center of anthropology. But, yes, Karl was another influence. There were these people that were reinventing action anthropology, influenced by Tax and Vicos. But--and also the Schensuls but mainly just it was popping up. I mean independent invention if we want to go back to that. And the Schensuls had begun to organize some symposia at anthropology meetings. I forget what they were called. I went to one. There was this discussion afterwards. And I got up and said whatever I had to say, and we began to find each other. Gwen Stern, who of course knew them. And there was a series of symposia at AAA and SfAA that led ultimately to two volumes. One was the Collaborative Research Westview book. The other was a special edition of American Behavioral Scientist that was edited by Jay and Gwen Stern. And that was the theoretical articles. And they were really supposed to be companion volumes. And the one was theoretical pieces and the other was case studies. But we were calling it all sorts of different things. And by that time, I had written--I and a former KU student had written a piece on action anthropology among the Kickapoo.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: And we sent it in to Human Organization. It got reviewed by one of the Sol Tax, you know the folks who had been action anthropologists under Sol Tax, and just got destroyed. It's not real action anthropology. Now, it should have been rejected but I don't think for that reason.

You know, the reason it was rejected was not because it was too long and it was too diffuse, which it was. It was because it's not lockstep the way Sol did it. You know that we were trying to take that idea and the things that people were talking about as action anthropology as folks have subsequently--Larry Stucki for example and others have subsequently said, you know, there was a lot of rhetoric in what people were saying about action anthropology. And the reality and the rhetoric were not the same. And we were trying to say, "Well, you know, we're taking it. We are developing it. We're building on it and we're trying to come to grips with it in ways that work for us in the 1980s.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And so finally I said, "Well, you know, if I can't call it action anthropology, it's something but if Sol Tax and the Fox own that phrase then we've got to find another label because what we're experiencing is different from them. We still have the same philosophy. We want to work from the bottom up. We want to do what the people want. But, you know, we are involved in making decisions. We are working alongside of these people as opposed to being their functionaries." And other people were trying to come up with terms. And there were a series of terms, sort of many of them mentioned in that Westview Press book. Collaborative research was the one that we thought was the best term. It turned out it wasn't the best term.

VAN WILLIGEN: What was the best term?

STULL: The one that won out is participatory anthropology. That's the one that really has ultimately become the one of the terms. I think they're all more or less talking about the same thing.

VAN WILLIGEN: Actually, in my textbook. What did I call it? Oh yeah. He called it action research. I called it in the course of writing that chapter community, community advocacy or something like that.

STULL: Yes, I think that's a good label for it.

VAN WILLIGEN: And that term that I used is different than what he called it. We had some interactions about it. I could tell that it didn't bother him one bit.

STULL: No.

VAN WILLIGEN: It probably would have made sense to him. Then for the third edition I called it collaborative anthropology.

STULL: You know, collaboration is a term that has certain negative connotations. But it's also become a term that has become increasingly popular. But not for what we were calling it. We chose the wrong term.

VAN WILLIGEN: You always thought of it as applied anthropology.

STULL: Absolutely, absolutely. For me action anthropology is applied anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: One kind of applied anthropology, as opposed to the Tax view which is it's something different. I think that's ridiculous.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. That whole book is based on the premise that in fact they're all different kinds of applied anthropology.

STULL: Sure. It's just different ways to skin the same cat.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: I've actually had for our doctoral program; we have students do what we call field statements. They're essentially position papers that they write, three of them, one under each of their major professors. And I've had several students look at the development, the evolution of participatory research, starting with action anthropology with Tax and going through collaborative research and on into what it's called today.

VAN WILLIGEN: --I see.

STULL: I've learned a whole lot from these students who have looked at it with fresh eyes and not with the emotional attachment that I had to it.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, I know what you mean.

STULL: And so, it's--but I think there is this is a natural I think progression. Natural is not the right word. But a progression of all trying to do the same thing. It's we've got to serve the needs of the people. We've got to do it from bottom up. We've got to work with them and how do we do that well? And, you know, action anthropology has gotten great press. I mean if you go back and look at it didn't really do very much. It was just a lot of rhetoric. Vicos, I mean I wasn't at either place but to me it seems like Vicos did a whole lot more. It has a very different reputation in anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, I mean that's more or less my view. It seems action anthropology in that original case seems kind of puny basically.

STULL: Yes, it is puny. And what's his name, I can't think, the guy from Tama, the anthropologist who's written the--

VAN WILLIGEN: --Fred Gearing?

STULL: Not Gearing. So embarrassed. I can't think of these names. He did a really nice piece in Current Anthropologya few years ago looking at Fox. Basically saying, "Well, you know, it really didn't do very much."

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. One of the Chicago group?

STULL: No, he wasn't, he was a high school student at Tama.

VAN WILLIGEN: And then so the influences at this period were the Schensuls,

STULL: --Schlesier, Vicos and Fox.

VAN WILLIGEN: And was there any influence from the kind of classic action research people?

STULL: No. There should have been but there wasn't, no, for me there wasn't.

VAN WILLIGEN: All the people you mention are anthropologists.

STULL: All of my--I mean this probably just shows my parochialness but all of my influences in what I was inventing in Kansas were coming from anthropologists. And it was really working in isolation for me.

VAN WILLIGEN: Sure.

STULL: And I think there were a lot of people that were working in isolation. And we were finding each other thankfully through the Schensuls and these seminars and the pieces that they were writing. The piece Steve Schensul wrote in Practicing Anthropology, "Commando Anthropology."

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: You know, it's a wonderful title. It's nobody's fault but my own. I was not reading that kind of other stuff beyond anthropology then. I since--I subsequently have but I wasn't then.

VAN WILLIGEN: Focusing on my view of the next episode of your professional life. That has to do with the Kansas meatpacking stuff. I'm not sure if there is a transition.

STULL: It was, I got into anthropology because of this abiding fascination and love of American Indians. And Kansas offered me this wonderful opportunity to study groups that had essentially been largely ignored. Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Iowa, Sac, and Fox.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: These are what are called emigrant tribes in Northeast Kansas, and they had been studied but not in Kansas.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right. Fox of Kansas is the same Fox of the--

STULL: --yes, as the Meskwaki.

VAN WILLIGEN: Meskwaki. I see.

STULL: And actually they--Meskwakis came back from Kansas, went back to Iowa, bought that land.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, yeah, I see.

STULL: But they had originally gone to Kansas, and said, "Forget this. (laughs) We're going back someplace that's civilized." There had been some early twentieth century stuff, there had been some research done on the Kansas tribes in the sixties. But they were essentially not virgin territory but, they were good to great. But they were hard to work with and periodically I took a sabbatical. And, I had a joint appointment about '79 I think or something. I was offered a joint appointment in the Center for Public Affairs, which was a research unit made up of community development psychologists and political scientists and a variety of social scientists doing policy research. And I jumped at that opportunity. It was taken over by business. And sort of a, we thought, hostile takeover. And they came to me and others and said, "You know, Indians are not in our future as a unit, and you need to do something else." And I was getting to the--

VAN WILLIGEN: --oh, I see.

STULL: --and I was getting to the point where--

VAN WILLIGEN: --this is the punch line.

STULL: --where--

VAN WILLIGEN: --this is the answer to my question.

STULL: (laughs)

VAN WILLIGEN: (laughs) That's interesting.

STULL: And so, you better do something else if you want to stay here. And an RFP landed on my desk. I almost--looked like junk mail. Almost threw it away. And I opened it up and it was a call for proposals from the Ford Foundation to do a study of the so-called new immigration. This was in 1987, '86, '87. And there was going to be a national study because they knew the '90 census was going to show this new wave of immigration and the growing ethnic diversity. And communities had to have multiple ethnic groups. There had to be teams of ethnographers that reflected the groups that the communities have. And I had read some newspaper stories about Garden City, Kansas, which is out in the southwest corner of the state, about Vietnamese that were coming to Southwest Kansas to work in meatpacking. Vietnamese in, you know, the plains of Kansas, that's really bizarre. And I had actually hitched a ride on the university plane, was doing a recruiting expedition, gone out there, met with Ken Erickson. He was Julie Uhlmann's student at Wyoming. He's since gone on and gotten a PhD in anthropology, is a practicing anthropologist. Yes. And so, he was refugee services coordinator out there. And somehow, we had connected. I don't remember how. I flew out. Ken showed me around. And this RFP came along. And so, I contacted Ken. There were some other people. Janet Benson, an anthropologist at Kansas State, was getting interested in Garden City. Michael Broadway, my longtime research partner, was at Wichita State, and he's a cultural geographer, and he had gone out and done some research. So. it just was kind of this convergence. And we had some meetings. We decided, Well, they wanted all the various ethnic groups that were coming to the United States. They also wanted geographic distribution. And they also wanted urban rural. And we thought, what the hell? I mean Kansas, Vietnamese in Kansas. And so, we wrote a preliminary proposal, you know, a couple pages. And they said, "Yeah, sounds interesting." And so, we got together.

VAN WILLIGEN: It's a pretty big team.

STULL: It was six people. Five anthropologists and the geographer. [This is in]

the late eighties, '86. We never got together in the same place at the same time until we had the grant. So, we did it all by--this was sort of pre-email. Well, it was BITNET. This was the age of BITNET. But we did a lot by phone. We would and we got that. And I directed that project for two years, '88 through '90. And none of us knew anything about Vietnamese. What attracted us was that Vietnamese were coming to Kansas. That's big, big news.

VAN WILLIGEN: It sounds so interesting.

STULL: But we had to have at least two new immigrant groups. When we started going to Garden City we learned, well, there are all these Mexicans coming too. And we needed someone who could do research on Hispanics.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: I called up Art Campa, who had been a classmate of mine at Colorado. He was still working at Colorado. And, I said, "You know, are you interested?" And Boulder was as close to Garden City as I was. It was sort of midway between us.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, okay.

STULL: So, we said, "What the hell? We'll do that." And, by golly we got it.

VAN WILLIGEN: Wow.

STULL: And so, I lived out there for sixteen months. And not all at the same time. But on and off for sixteen months. And I got interested in the industry because that's what was drawing people to Garden City. And so almost twenty years later I'm sort of the bestial anthropologist. That's my specialty, bestiality, I guess.

VAN WILLIGEN: It's quite interesting. But it's sort of an accident.

STULL: It was very serendipitous.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. And then the fact that it was Vietnamese.

STULL: And, and Ken was--

VAN WILLIGEN: Just seems interesting.

STULL: Well, I had started to get interested and I thought, you know, I'm not going to learn Vietnamese.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: I mean what can I do that will get me out there looking at it without having to--I mean I'm just not going to learn Vietnamese in time to do this. And I thought, well, you know, anthropologists, well, we always look from the other side. Why not look at us and how we're receiving these others? And I thought, well, heck, I can do that. And so, I had gone out and talked to Ken a little bit. And we had talked about some ideas. Then along came this. He's a fluent Spanish speaker. He now is a fluent Vietnamese speaker. He was pretty good then. He's now picked up other things like Thai and so forth. He's an accomplished musician. He's so skilled. So, we put together a team that had the language skills. And none of us had them individually but well, Ken did, I guess. But--and so the team was able to do that. And we played to our strengths. My specialty was the workplace and Anglos and different people and different things.

[Pause in recording.]

VAN WILLIGEN: And, it had a social policy aspect built into it, which I can hear in your discussion of Kentucky tobacco farmers even.

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: You know, so it's still there. So, there's a certain amount of policy heat associated with it. Yet has a kind of intractability that calls out for somebody to study it and make sense out of it.

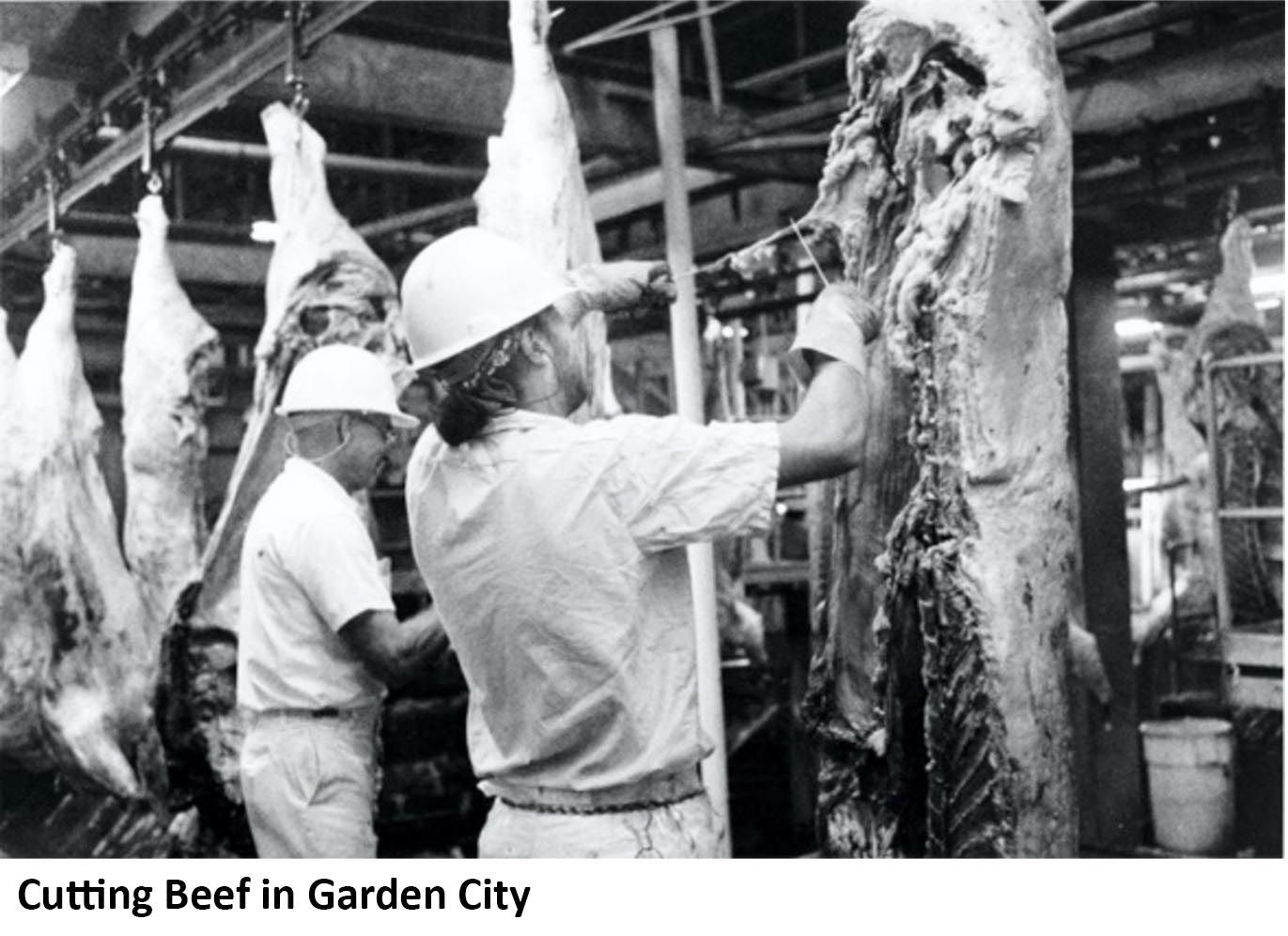

STULL: And, you know, interestingly I guess I was one of the first people to get into the meat business as a social scientist. But it's attracted anthropologists. If you look at the people who are studying the meat and poultry industry, they're almost all anthropologists.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, I see, that's really interesting.

STULL: David Griffith for example, Mark Grey, he was part of the Garden City team. Steve Striffler now who's at Arkansas who's got a new book out called Chicken. There are some other folks. Deborah Fink in Iowa. They're virtually all anthropologists. They tend to get attracted because of the immigrant issue. But they're often pulled into the issue of workplace, of worker rights and safety and those kinds of things.

VAN WILLIGEN: It is really interesting as new fields emerge, a lot of them you find there's a huge influence of anthropologists, whereas if you kind of backtrack you find more mature fields, the anthropologists are a tiny minority, and they're still kind of nibbling around the edges. The other area that I know there's huge influence from anthropology in fisheries research.

STULL: Oh yes, yeah.

VAN WILLIGEN: And one could probably make a list of topics.

STULL: The fisheries Mafia is what I was told when I became the editor of Human Organization.

VAN WILLIGEN: They were there at the beginning, and they dominate it.

STULL: Yes. (laughs)

VAN WILLIGEN: It is quite interesting really. So, a question I have on my list here, there was no particular interest in meatpacking.

STULL: No.

VAN WILLIGEN: There was something--it was something about this RFP.

STULL: It was all about immigration.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: And really none of us were--I mean I was an American Indian specialist.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And the other people that were brought in were specialists in--well, Janet Benson was a specialist. Her specialty had been India. She had gotten interested, but she didn't know a damn thing about Vietnamese. And none of us did. But we all were able to sort of fake it, I guess.

VAN WILLIGEN: Sure.

STULL: And write a proposal that was fundable. And we then were drawn in by the immigrants and that experience and then for me, the industry became this incredibly interesting phenomenon. That has led to more of a focus on the industry and what it does to communities and workers and immigrants are still a very important part of it but probably they've drifted. I don't want to say to the background. But I guess sort of to the background.

VAN WILLIGEN: How did you happen to pick Garden City. Was that because it was in the media?

STULL: There were. The first story I read was about Garden City. But there are three communities in Southwest Kansas. Garden City, Dodge City, and Liberal. They're called the golden triangle of meatpacking. They all have beef plants. Our original proposal was to study all three. Because Dodge City sort of looks to its historical cowboy, you know, Gunsmoketradition. We had heard that Dodge was conservative and wasn't handling its immigrant population well, that Liberal, which is down on the Oklahoma border, was liberal, was doing a good job. They all have Hispanics and Vietnamese and Anglos but Liberal has a black population too of some substance. And Garden City was sort of in the middle. And we originally proposed to do all three. But the Ford Foundation said, "We, we don't have enough money to give you to do all three. And you're not going to be able to do a good job. So, if you want to be competitive." We submitted this preliminary proposal with all three. And they said, "You've got to choose one of them." And so, we made the decision, and I think it was the right decision, to go to Garden.

STULL: There were. The first story I read was about Garden City. But there are three communities in Southwest Kansas. Garden City, Dodge City, and Liberal. They're called the golden triangle of meatpacking. They all have beef plants. Our original proposal was to study all three. Because Dodge City sort of looks to its historical cowboy, you know, Gunsmoketradition. We had heard that Dodge was conservative and wasn't handling its immigrant population well, that Liberal, which is down on the Oklahoma border, was liberal, was doing a good job. They all have Hispanics and Vietnamese and Anglos but Liberal has a black population too of some substance. And Garden City was sort of in the middle. And we originally proposed to do all three. But the Ford Foundation said, "We, we don't have enough money to give you to do all three. And you're not going to be able to do a good job. So, if you want to be competitive." We submitted this preliminary proposal with all three. And they said, "You've got to choose one of them." And so, we made the decision, and I think it was the right decision, to go to Garden.

VAN WILLIGEN: Garden City was sort of in the middle.

STULL: It was in the middle, geographically, but more importantly we had heard it was progressive, that it was doing a good job, it seemed to be if you had to choose one of them, it seemed to be the place to study. I've subsequently done research in Dodge City, not in Liberal, I still think that Garden has been the more progressive of the three communities. It's been the right choice I think for us to do the research. I've had a student, one student, that's done research in Dodge City. And I continue to encourage people to work out there. I have yet to get anybody to do Liberal. But we've had some research in other communities out there.

VAN WILLIGEN: What was your impression of when you first went to Garden City. What did you think of the place? Well, of course you had been in Lawrence.

STULL: Well, there's no comparison. I mean Lawrence looks a lot like Lexington. Not as many trees. Not as green. But it's rolling and Garden City is flat. It's the plains. Trees are in short supply. I love it. You know, for me it was partly the attraction. I come from a farming family. Both of my parents were born to families in Webster County [Kentucky] that had owned farms in that county since the early 1800s. They were early settlers. Agriculture is the only legitimate occupation in my family. There is no other. Yes, people work at other things but it's not real work. It's not. And I don't believe that but it's very hard, it's hard to abandon that. You know, it's a visceral kind of thing. So going to Garden City was for me in many ways a wonderful chance to get back into a world that I valued. It just made me feel good, I guess.

Interestingly, some of our team--we had a Puerto Rican. We had two Latinos to begin with. Art Campa and then a Puerto Rican who was an educational psychologist who was going to do the schools. And he bailed out after about three months. He was from Chicago, was Puerto Rican.

For me it was this wonderful return to, to agricultural communities and I just loved it. It's this desolate beauty that I just find wonderful. That's not really an answer to your question but it's a visual and an olfactory experience. You drive into there. You smell the feed yards. They call it the smell of money. It's windy, it's dusty, it's flat. It's great. (laughs)

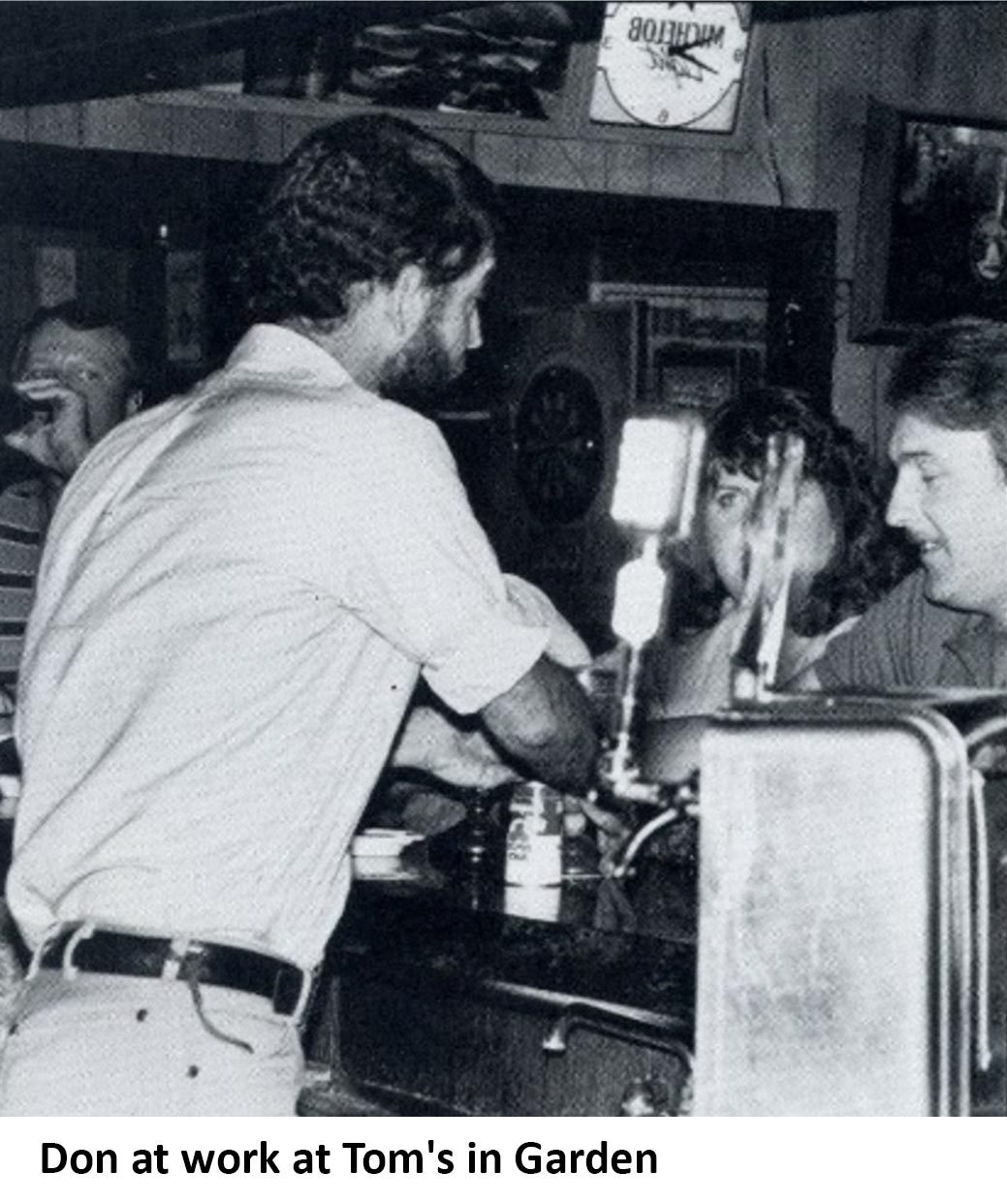

VAN WILLIGEN: What did you do for your spare time when you were there?

STULL: Well, I was a bartender for a long time in Garden City. We discovered this place called Tom's Tavern. I had a former student who was from Garden City in Lawrence. And we became good friends, and I said, "Well, I'm going to go out there and do research," and he was from there. His family is very prominent there. And so, he said, "You got to go to Tom's." So, Michael Broadway, my geographer buddy, and I went in there one day. It doesn't say Tom's on the outside--it's just this nondescript building, this long white building. There’s a Budweiser sign in the window.

VAN WILLIGEN: It's not a concrete block, is it?

STULL: No. But it might as well be. And we went in there one day. We bellied up to the bar and sat down. It was the day when the press release about our project had come out. And this,

woman she would have been in her late forties, early fifties, big beehive hairdo very rotund, came up, and we were sitting down there, and she said--you know, talked to us, who are you, what are--what are you doing here? And we told her. And she didn't know what to think of us. Well, Michael is a Brit, and he has a very British accent. And we spent about thirty minutes with her trying to place where it was from. Well, it's from the East. How far east? And it kept going, finally got to Britain. And so, then we came back in later. And it became our headquarters. She would ask us who wrote our dissertations and that kind of stuff. She's wonderful--her name is Joyce. A wonderful lady. It was like Cheers. I mean it was--it really was a community bar. And, any newcomer that came in, she would immediately--they called her Chopper because if you didn't do it in your living room, you didn't do it there. And a lot of things you did in your living room you didn't do there. Whistling was not allowed. Putting your feet on the tables, not allowed. You could cuss but--and she sat at the front table and people walked in and she screened them. And people played Trivial Pursuit and those things. And I became a regular there, because, you know, you can't talk to people. They're working during the day and stuff. But they came in there at night. The meatpackers came in there at night.

VAN WILLIGEN: These are people that are actually cutting.

STULL: These are the people that are actually cutting it. In the afternoons it might be the managers, or it might be the feed yard owners, or it might be the lawyers. There are three shifts in a meatpacking plant. The first one is from 7:00 in the morning till 3:00 in the afternoon, then 3:00 till midnight, and midnight till 6:00. And I spent much of my time there because it was a place where people would talk, would come and, you know, people talk about their work. And so, then she needed some extra help and she said, "Would you like to tend bar?" And I said, "Sure." Because it gave me an opportunity to be there and not drink.

VAN WILLIGEN: Um-hm.

STULL: And I thought, This'll be great, you know, I'll be like Sam at Cheers, I'll sit there, and they'll tell me all their stories and I'll--of course she had me working at the times that were the busiest times. I worked from midnight to 2:00 on Thursday nights. Thursday was pay day.

VAN WILLIGEN: Midnight to 2:00?

STULL: Midnight to 2:00. And then I worked from 10:00 to 2:00 on Sunday nights. Sunday was called zoo day. It was the only day off. And it was the day when people just, you know, just let loose. And so of course most of the time I was slinging beers and doing stuff. But every once in a while, I got to talk to people. But it gave me a legitimate occupation. And, so I spent--I tended bar and spent much of my time there, and that's where I spent most of my time. And, uh, it still is something that people find--they like it there when I go back. They still talk about that and they still like the fact that I did that. I miss Tom's. It was a great place.

VAN WILLIGEN: What are the landmarks of your work in that context in the meatpacking?

VAN WILLIGEN: What are the landmarks of your work in that context in the meatpacking?

STULL: I think our landmarks are both in Garden City and elsewhere. We began describing Garden City because we believed it was a cosmopolitan community, one that was not perfect but was trying really hard.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: And was doing not too bad a job of dealing with this influx of people from Vietnam and Thailand and Guatemala and El Salvador and Mexico. And really trying hard and we began saying, "You know, these people are doing okay. This is a cosmopolitan place." It is in my opinion the most exciting town in Kansas. It's now a majority minority community. When we first went there, it was about 16 percent Hispanic. Most of those were Mexican Americans who had come or whose parents had come after the revolution. And now it's over 50 percent Hispanic. The vast majority are from Mexico or Guatemala or El Salvador. New immigrants. And they have really looked to the future and said, "We're going to be the face of America in the future." Dodge City looks to the past. They look to Matt Dillon and Gunsmokeand they have the same dynamic, but they don't deal with it the same way.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

STULL: [Garden City] they have really--part of it is a self-fulfilling prophecy. We said, "This is a cosmopolitan community." They said, "By God, we're cosmopolitan." And they have dealt with it that way. And we did reports for the school system and, and the city and Michael was just out there last week giving a talk about our research to businessmen.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, the research is still going on.

STULL: It is. We continue. Michael and I continue to go back on a regular basis. More importantly, Garden City has become an exemplar for other communities. And so, when we finished our research in Garden City, a new beef plant was opening in Lexington, Nebraska, about two hundred miles north of there. And we said, "Well, you know, we've learned a lot. But is what we've learned here, is that true of other meatpacking towns or is it just Garden City?" So, we're going to find out. And so, we went up there. But we also met with the people there and said, "We've learned this about Garden City. We think there are some lessons that you--could help you in terms of your adjusting to this new dynamic." And so, we've worked with towns in Oklahoma, Nebraska, two provinces in Canada, Manitoba and Alberta.

VAN WILLIGEN: Wow.

STULL: Minnesota. And I think that we've helped mitigate some of those dynamics. Now we--and we've actually--we've met with communities that were thinking about meatpacking plants. Some of them have resisted them and decided not to have them.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, you go to the meetings of the leadership of these communities?

STULL: People learn about us, and they invite us there and we say, "It's not for us to decide whether you want a meatpacking plant. That's your decision. But you're getting all this pie in the sky stuff from," we don't call it that, but from "the meat plants.” “Here's what's going to happen from the social side. Here's what's going to happen in terms of schools and all these other things. And you have to decide, Is this what you want or not?"

VAN WILLIGEN: It's like you develop this cumulative understanding of the social impacts of meat plants. And you without telling people what to do exactly.

STULL: We're the wet blanket. We say, "Well, you know, this."

VAN WILLIGEN: You know, you have to think about this.

STULL: You have to think about this.

VAN WILLIGEN: This, this is not part of--

STULL: --essentially--

VAN WILLIGEN: --the information that you get from--

STULL: --essentially what do these jobs cost you?

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

STULL: They're going to bring in a certain number of jobs. They're going to bring in a certain amount of payroll. Those jobs are going to be taken primarily by people that don't live here today. And they're going to do this to your schools, they're going to do this to your health care system. Do you want this? And if you do, fine. But if you do, you better do X, Y, and Z.

VAN WILLIGEN: It's kind of a social impact assessment.

STULL: It is a social impact assessment.

VAN WILLIGEN: A lot of social impact assessment had kind of a black box quality. And what I hear you saying or the implication of what you're saying to me is that well, in fact you knew what the impacts were in Garden City. And so, you can communicate to people in these new places what these impacts are before--

STULL: What I like to say is that we have developed from ethnographic research in Garden City and other places we have developed an ethnology of meatpacking. So, we can say with a great deal of confidence, "We can't tell you exactly when it will happen, but these are the things that will happen."

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. Have you written anywhere; I imagine that these elements all appear somewhere in the things you've written.

STULL: Yes, I'll give you a copy of Slaughterhouse Blues. It's got that in there. I mean I'll be happy to.

STULL: Yes, I'll give you a copy of Slaughterhouse Blues. It's got that in there. I mean I'll be happy to.

VAN WILLIGEN: I wanted to ask you a little bit about you being the editor of Human Organization.

VAN WILLIGEN: I mean it seemed like it was something that's ended recently and--

STULL: --it was--it, it ended recently.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, I mean it seemed like it went really well.

STULL: It was, as I told you earlier when I was at UK Marion Pearsall was the editor. And I got introduced to it, was allowed to take the dusty copies. And it became this special thing to me. I went to Colorado. And then Human Organization, the editorship went to Deward Walker. My first publication was in HO. So, it's always been this magical thing for me. And so when I became editor, it was seven years ago, my last sabbatical. I was working on that in Sebree. It became a, I mean it just is a special publication for me. I got to see; I think the best that applied social scientists are doing. And I got to have an opportunity to influence that in some way and guide it in some way. I'm very grateful for the opportunity. I learned a lot. I mean I had coedited Culture and Agriculture before. And I learned a lot about the editing process that I didn't really know.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: I did the copyediting myself. And Neil Hann at, at Oklahoma City was the production editor. My wife Laura did the graphic design, the maps and stuff.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: One of the things that I appreciated about it was I had the opportunity to hire a bunch of students who were able to work on it as my assistants and gain editorial experience. You know, I loved doing it. I did a lot of looking at the ethnicity and gender and, and where people are published, you know, who--where articles are coming from and countries and I mean it wasn't particularly surprising but one of the things that I was surprised by, there's this debate about Human Organization about who's publishing in it.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

STULL: Are they practitioners, is it academics, and so forth, I think Human Organization gets criticized often unfairly for being too academic and so forth. And I looked at that. And interestingly, about half of the articles that we published were from nonanthropologists. And, uh, a significant number were from practitioners. And so, I felt very good about that. I think that it does represent the field of broad social science well.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, I always felt that it had a lot of academic, I mean I would have said something like that myself.

STULL: Yes. Well, I think most of us would have but it's not really that way necessarily.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right, I share much the same view. I mean I didn't have quite these hands-on mystical experiences with it, but I always thought it was the place where one--where I would want to send stuff.

STULL: Well, I'm probably more defensive of it than, than many people would be. But I think it's also a more readable journal than American Anthropologist. I have a hard time finding an article I want to read in American Anthropologist. And that's not usually true in Human Organization.

VAN WILLIGEN: I have always liked the journal. One story I'll relate to you is that when I, it must have been my first--wasn't my first publication but it was certainly [an]early publication, maybe the first publication in Human Organizationand important to me. There is a typographical error--

STULL: (laughs)

VAN WILLIGEN: --in the title.

STULL: Oh ho, oh.

VAN WILLIGEN: And the editor was Deward, and he caught it and pasted in a correction, a label. And it was like the most--I mean to me an absolutely generous responsible act, because the word was misspelled. I mean I didn't misspell it. And he fixed it, I mean I visualized someone, maybe him, I don't know, sticking (slaps) a correction on each one. (laughs)

STULL: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: You know, and I, I said, "My God, that's intense responsibility." You know, I thought that was great that someone would b--I mean if he had said, "Well, you know, it's really too bad but"--

STULL: --"it's too late now."

VAN WILLIGEN: --"you know, it's too late now," I would have said, "Okay, well, fine." I mean that would have been a reasonable response. But he fixed it, you know.

STULL: Good for Deward, it's been a journal whose caretakers have been, I think very careful with it and--

VAN WILLIGEN: --right.

STULL: --and I feel very honored to have been one of those people. I think it's a treasure of our discipline.

Further Reading

1978 D. D. Stull. Native American Adaptation to an Urban Environment: The Papago of Tucson, Arizona. Urban Anthropology 7:117-135.

1986 D.D. Stull, J. A. Schultz, and K. Cadue, Sr. Rights Without Resources: The Rise and Fall of the Kansas Kickapoo. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 10(2):41-59.

1987 D.D. Stull and J.J. Schensul, eds. Collaborative Research and Social Change: Applied Anthropology in Action. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

1995 D.D. Stull, M.J. Broadway, and D. Griffith, eds. Any Way You Cut It: Meat Processing and Small-Town America. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. 2

1998 K.E. Erickson and D. D. Stull. Doing Team Ethnography: Warnings and Advice. Qualitative Research Methods Series, No. 42. Thousand Oaks, Calif.

2000 D.D. Stull. Tobacco Barns and Chicken Houses: Agricultural Transformation in Western Kentucky. Human Organization 59:151-161.

2004, 2013 D.D. Stull and M.J. Broadway. Slaughterhouse Blues: The Meat and Poultry Industry in North America. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth.

2017 D.D. Stull. Cows, Pigs, Corporations, and Anthropologists. Journal of Business Anthropology 6(1):23-40.

Cart

Search