An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Creating and Managing an Anthropologically-Oriented Consulting Firm

Creating and Managing an Anthropologically-Oriented Consulting Firm: A SfAA Oral History Project Interview with Niel Tashima and Cathleen Crain

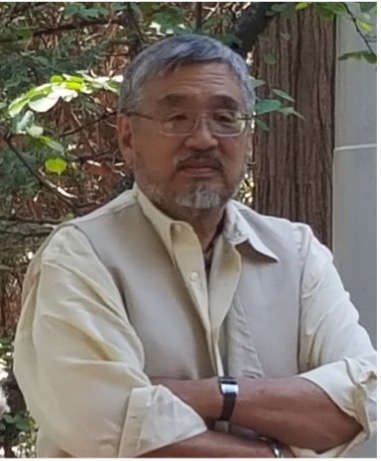

Niel Tashima and Cathleen Crain are the managing partners of LTG Associates, a consulting firm which they formed in 1982. LTG Associates is uniquely based on anthropological concepts and practices as well as owned and managed by anthropologists. Their work is done locally, nationally and globally for a number of firms and associations and is focused on planning and providing culturally appropriate health and human services. In 2015 they took LTG Associates in to the virtual world; and since then the company has operated in the virtual space. Both maintain effective participation in anthropological associations. Both have served as president of the National Association for the Practice of Anthropology and have provided other services to disciplinary organizations. Tashima received his undergraduate training at UC San Diego, and graduate training at San Diego State University and Northwestern University. Crain did her academic work at McMaster University in Canada. Niel and Cathleen are adjunct faculty in anthropology at the University of Maryland. The interview was done on April 1st, 2011. The interviewer was John van Willigen who also edited the transcript.

Niel Tashima and Cathleen Crain are the managing partners of LTG Associates, a consulting firm which they formed in 1982. LTG Associates is uniquely based on anthropological concepts and practices as well as owned and managed by anthropologists. Their work is done locally, nationally and globally for a number of firms and associations and is focused on planning and providing culturally appropriate health and human services. In 2015 they took LTG Associates in to the virtual world; and since then the company has operated in the virtual space. Both maintain effective participation in anthropological associations. Both have served as president of the National Association for the Practice of Anthropology and have provided other services to disciplinary organizations. Tashima received his undergraduate training at UC San Diego, and graduate training at San Diego State University and Northwestern University. Crain did her academic work at McMaster University in Canada. Niel and Cathleen are adjunct faculty in anthropology at the University of Maryland. The interview was done on April 1st, 2011. The interviewer was John van Willigen who also edited the transcript.

VAN WILLIGEN: This is an interview for the SFAA Oral History Project with Niel Tashima and then a little bit later on Cathleen Crain will join us. And it’s the first (laughter) of April.

TASHIMA: Seems appropriate.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yeah, I was a little bit worried about this, because this is not a mock interview. (laughs) We’re in Seattle at the SfAA meeting. So Niel when did you start being involved as an anthropologist? What led you to anthropology? Where were you and all that?

VAN WILLIGEN: Yeah, I was a little bit worried about this, because this is not a mock interview. (laughs) We’re in Seattle at the SfAA meeting. So Niel when did you start being involved as an anthropologist? What led you to anthropology? Where were you and all that?

TASHIMA: Good mentors as an undergraduate, Joyce [B.] Justus was the first professor I took a class from at UC, San Diego. She was asking interesting questions about why people did things the way they did. And I thought, ‘Well, this could be kind of interesting.’ And it was also a good option because I wrote good anthropology papers and wrote crummy organic chemistry tests. (laughs)

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And it worked well. And she got me engaged in several projects as an undergraduate that were just fascinating.

VAN WILLIGEN: You started out as a cultural anthropologist.

TASHIMA: Actually, I started out as a psychological anthropologist--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And the department I was in, UC San Diego, there was only psychological anthropology. And so I took classes, and I assumed that’s what anthropology was. It never occurred to me that there would be a four-fields approach. Because [at UC San Diego] those three fields didn’t exist. And so you became a psychological anthropologist, acknowledging you were part of this cultural structure. It wasn’t until I started working on my master’s at San Diego State that I ran into the four fields. And so I was sort of tooling along doing psych-anthro and having a perfectly good time. And so UCSD was a really interesting place to be at that time; it was a relatively new university, so there weren’t as many rules and regulations about how one went about getting a degree. And so I took classes in extension education and anthropology for my last two years, basically.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And education was a fascinating place to be at that time, in the early seventies. Because of the whole orientation towards cultural knowledge about educating high school students, and so the two fields fit together pretty well--at least in my mind. And then I think the last year I was at San Diego, the American anthropology meetings were there, and my major professor, Ted Schwartz, was a student of Margaret Mead’s--Margaret Mead came and lectured one of our classes. And in her lecture, she talked for about two minutes about her work in the Japanese camps during World War II. And this was the major project I was working on at that point. And so I thought, ‘What the heck? I’ll go ask this woman these questions.’

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: And so I cornered Margaret after class was over, and I asked her about this, and she said, “We should talk. Why don’t you come up to the room I got and we’ll have tea?” And so the university unbeknownst to us undergraduates--on top of one of the dorms had a wonderful suite that looked out over the Pacific Ocean and so for four hours, as the staff that serviced this--served us tea and cookies, Margaret had this four-hour chat with me about anthropology. And we watched the sunset. It was one of those wonderful things you do--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, yes--

TASHIMA: Wow, how cool.

VAN WILLIGEN: That’s really remarkable. And what do you remember about that encounter with--I mean, the things you might have talked about?

TASHIMA: It was a synopsis of her career which I found fascinating. I mean, we’d all read her things. And because Ted had worked with her, there was probably a closer connection to her work. But she started in her Pacific work and work through her career. It was just kind of a story of her life.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And some of the intellectual challenges she had run into about being an anthropologist, being, and she didn’t call it an applied anthropologist, but she called it “working outside the university.” I remember this very clearly and how that invigorated her academic work.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And I think that’s partly where my bias comes from, that the discipline needs both the professional and the academic side--that neither one of us will survive well without the other.

VAN WILLIGEN: That’s a really a good point for you to bring up because people would be interested in that, you know. At what point did you see the relationship, it dates from this period--

TASHIMA: Yeah. This is ’73, ’74, ’72. Somewhere in there. And it was just a basis for what I thought anthropology was supposed to be and it wasn’t until much later that I started realizing what kinds of divisions occurred within the discipline, and sort of the historical process that all created for us. And trying to knit that together has been a fun process. That’s partly why Cathleen [Crain] and I got engaged with Triple A and SfAA. When Yolanda Moses was president of Triple A she talked about the five fields and that practice was the fifth field. And I like that. I like that sense of integration, of partnership of how this all should work. I’ve had wonderful mentors in the c--anthropology field all along. Joyce Justus was one of the first. Barbara Pillsbury at San Diego State was another one who pushed me to think very clearly about what it was I was trying to say about Asian-American mental health at that point.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: And as a graduate student at Northwestern, Francis Hsu spent the year talking with me about how he saw anthropology and his mentors. It’s a very different orientation to learning.

VAN WILLIGEN: So your last degree in anthropology was from Northwestern.

TASHIMA: Yes, and I spent a year in a medical sociology PhD program before going to Northwestern. I was in the last qualifying exam, and this was a, I think, a national computer data set on a computer terminal, and they gave you three questions, and you were supposed to come up with your analysis. I looked at it and I thought, ‘I don’t want to do this.’ (laughs) ‘There’s no people involved in any of this. I can’t talk to anybody.’ So I picked up my blue book and turned it in and walked out. And figured I’d go home, work for a while, and try to do something with anthropology again. And I--Francis was president of Triple A that year--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: As long as I’m in Chicago, I should go talk with him about how he sees the of American Anthropological Association. And he kindly enough said, “Well, come on up, we can chat.” And so we talked for a couple of hours, and he invited me to join the department as a graduate student the next fall.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And so I spent a year studying with him as well as the rest of the faculty, but mainly talking with Francis about his view and experiences as an anthropologist.

VAN WILLIGEN: And are you from California?

TASHIMA: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. Southern California.

TASHIMA: Central California, actually, I’m a fourth-generation Californian, which puts me in a very unusual state for anybody.

VAN WILLIGEN: Sure.

TASHIMA: One of my great-grandfathers had a boarding house for Japanese people in San Francisco in the late 1880s. And my grandmother--his daughter--was born in San Francisco in 1888, I think.

VAN WILLIGEN: And so you must have had relatives that were relocated.

TASHIMA: All the family was.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: On both sides. And the community I grew up in was an exceptional place to grow up. This was my dissertation research, it was an intentional Japanese-Christian community.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And in 1907, a Japanese bank advertised for Japanese families from southern Japan on the West Coast of the US to come join this colony and create a Christian colony in the United States. And so my grandfather was one of the first wave of immigrants to come, and our family has had roots there ever since. And it’s been an interesting, very stable thing, and my mom’s side of the family, the family was living in one place in Japan. We can trace our history back to the 1300s. And, you know, it’s a very bounded place And that side of the family came to the US, and we didn’t move again, so my family’s--on my mom’s side--been in two places since the 1300s. My generation and the next generation are scattered all over creation. One of my cousins has been working in international development. Cathleen and I move around a lot.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: But it’s been a very different kind of experience for my generation. And so anthropology’s kind of fit that all well together.

VAN WILLIGEN: That’s really interesting. So, when you were a graduate student, you had this early view of anthropology as having two aspects and that you want to emphasize both aspects and the interaction between them, and--I mean, you (laughter) thought on those terms.

TASHIMA: Yeah, well, alongside the anthropology, I was also learning to be a community organizer.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And so that was a very practice-action-oriented activity. This was the mid-seventies, and I got involved with the whole Asian American movement around community mental health. And it was an interesting place to combine research with activism.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: There were no community-based organizations in--and at that point there was the National Institute of Mental Health statistics, I think they had--Asian Americans had no mental health problems, because we didn’t go to services. So the argument was, “Since you don’t use services, obviously you don’t have any problems.”

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: And within the community, we all understood that there were problems that communities couldn’t identify because you didn’t have bilingual, bicultural services. People wouldn’t go. And so it was all dealt with inside communities. As soon as you started opening up community-based programs that spoke appropriate languages, you saw rates go through the roof which made NIMH even more uncomfortable because they said, “There’s lots of crazy people out there. This probably isn’t good either.” And once you normalized access, it started to even out again. I got involved very early in this process, and so I helped create the first Asian American mental health program in San Diego. I was a real gofer at that point setting up tables, holding up the charts and things like that. But learning how one works in community to organize around an issue. And I was going to graduate school at San Diego State at that point.

VAN WILLIGEN: And you were studying not anthropology, but--

TASHIMA: No, I was doing anthropology. I was learning the community organizing from social workers who were doing it, and they wanted to know something about how you would research this.

VAN WILLIGEN: Just briefly: What are some of the people that influenced that work?

TASHIMA: Oh, there was a whole group of Asian American social workers. Anne Hsu, Beverly Yip. These are San Diego people. George Nishinaka in Los Angeles. There was a very influential community-based organization in LA called special services for groups, and they were an NIMH grantee among other things, they did direct services in LA. But they got an NIMH grant to form the first pan-Asian community-based organization, and it was called the Pacific-Asian Coalition. They got a second grant from NIMH to form the Pacific-Asian Mental Health Research Center and I became the first full-time staff to that program. And so I was learning community-based organizing in San Diego; I became staff to this national program where we’re talking about advocacy research that could be fed back to communities to demonstrate need and help create baselines and things like that and so I was learning from demographers and very few qualitative people. They brought me to do that, which I thought was sort of interesting. But again, I was using good anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And so I got to work with Filipino laborers up in the Central Valley of California, looking at how to assess their needs for healthcare and retirement programs at that point, working with a variety of human-service agencies in southern California to help form collaborations, and common agendas. And then in 1975, [as] staff, I helped create the Vietnamese mental health program at Camp Pendleton. And my boss at the time, who was the PI on the Asian American Mental Health Research Center, was a Chinese-American psychiatrist working at the VA in San Diego and at the medical school. And as things started to unravel in Vietnam towards the end of spring ’75 he said, “I want you to do some background work on Vietnamese culture, because we will receive some Vietnamese sooner or later. It would be kind of good if we knew how to do this from a mental health perspective.” And so, you know, in a very short period of time, it was clear that there wasn’t any, and that was easy to tell. He said, “Okay. Well...” He hooked up with psychiatrists of Naval Health Research Center of San Diego, and they were saying, “It looks like this is going to happen pretty quick.” And we started doing our background work beginning of March of ’75, and on May first, we opened up a counseling program for arriving Vietnamese at Camp Pendleton. And it was sort of an amazing, bizarre, kind of scary place to be for eight/nine months. But we worked with the arriving refugees and identified the first unaccompanied minors, which was an entirely new concept, because Vietnamese were coming as family units, and all of a sudden, individual kids started to pop up in the camp population that weren’t associated with people.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And what we found out was that families were being given children by their friends to get out of the country, and once they got to Camp Pendleton, they realized that if you had a larger stated family, it was harder to get sponsored out. So they would let these kids go. And nobody had anticipated anything like this happening, so we had no response, and the response we created was to create a program specifically for them. And these kids were probably the most traumatized out of everybody coming through.

VAN WILLIGEN: I can imagine.

TASHIMA: And so by, probably by August, we had three hundred kids in the program and they ranged from infants through teenagers.

VAN WILLIGEN: Wow.

TASHIMA: One of the interesting things was that San Diego City Human Services swooped in fall--I don’t know when--and said, “These kids need to go into our programs.” And they took the kids out of the camp and denied access to everybody outside their system, so we have no idea what happened to them.

VAN WILLIGEN: Huh.

TASHIMA: And we had Asian American child psychologists and social workers who would work with traumatized kids, saying, “We should be allowed to help.” And the system said, “No. Because of confidentiality issues, we can’t allow you access.” And so I think kids pop up every--well, they’re adults now--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: But they pop up in different systems, and every so often, you know, I see a success story and I wonder, ‘Wow. I wonder if that was one of the kids.’ Or you see somebody in real trouble--

VAN WILLIGEN: That’s what I’m wondering from the perspective of many years later how their lives turned out.

TASHIMA: Yeah. And through that there was a network of anthropologists across the country who were working resettlement that we ran into, met, and started to see at the association meetings, both SfAA and Triple A. And we keep saying we should do a retrospective at some point, because there were no systems in place, everybody was making things up as they went along, and a lot of it was informed by the anthropologist in whatever program that was operating. So you had a chance to really engineer things, to listen to the cultural aspects, to listen to language and try to figure out how to make it work better.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh. That’s really something. Is there anything else from this, before you started the firm (laughter) that you that you think is important for me to know?

TASHIMA: I think one of the important things is that anthropology can be taught. But to become an anthropologist, I think you need mentors.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: And that’s one of the things I’ve had access to all along, are people--are anthropologists who were very concerned about me developing well as [an] anthropologist. And pushing me intellectually to be rigorous, to do the kinds of disciplinary work one needs to do to become a well-rounded anthropologist. And so at San Diego State, I had to start over again, basically. I discovered that archaeology and linguistics and biological anthro all have things to offer me in the work I do now, which is very weird but is kind of neat to see all that come together. And when I was at Northwestern, I did the same thing. Each time I went through a program, it reinforced the idea that anthropology as a holistic discipline is critical to the way you think.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: You may never go on a dig once you finish graduate school but having the discipline that is engendered by doing that kind of work forces you to think about other things when you’re marching through creating a questionnaire or looking at something. It forces you to think differently. Because of the year I did in medical sociology, I know how you formulate questions and how you design work there. And the process is different. I can design a whiz-bang survey that meets all their criteria, rigorousness and, um, methodological appropriateness, but it doesn’t really consider how people fit into this. It doesn’t leave room for their interpretation of their experience to filter into the research process. And so when we design surveys that meets all the criteria a survey researcher would want but it also has room for people to provide interpretation. And, you know, in our professional world right now, that’s one of the critical elements. But having that lineage of anthropology and talking to people like Francis Hsu who go back now two generations--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: --gives you a fascinating historical perspective but it also says that the way we are trained to think is anthropology.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: And, that’s been the underpinning for what I do and how I think about this.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, Francis Hsu is a later but important influence on the way you think about things.

TASHIMA: Each of the people I’ve worked with have helped me focus and crystallize how to think like an anthropologist. And they’re all saying basically the same things, which I find, again, fascinating, that from Joyce Justus through Barbara and Francis, you get the same kind of perspective. You understand how you frame questions. How you see the world. And when I was in medical sociology, that didn’t happen. And maybe it was the program I was in, but it wasn’t a framing conversation. There are technical skills you developed and you had your overarching research question. And as I go to meetings--as I talk to other people--again, that’s what I hear coming from them. That’s the anthropology in all of this. And so we can sit and have these certain, far-ranging conversations, but it comes down to how you see the population you’re working with and the community you’re in.

VAN WILLIGEN: I think it might be a good point to pause.

TASHIMA: Okay.

VAN WILLIGEN: So that we can get Cathleen’s perspective on her experiences. And then we can talk together.

CRAIN: (laughs) So the first sound we heard was laughter. (laughter)

VAN WILLIGEN: And so, what led you to anthropology and where did that happen and what were some of the influences that had happened to you?

CRAIN: Well, I was going to be a physician from the time I was eight years old.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: Eight years old. I wasn’t going to be a nurse. Nothing else. I was going to be a physician. And I went through school planning for that; I was part of future doctors; you know I grew up with and all that geeky stuff. Went into pre-med. I worked whenever I was in school, I worked as well. I worked in healthcare settings. And what it did was it created a disenchantment for me with healthcare.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And I actually quit university in my senior year--I was not in anthropology; I was in pre-med--I quit university in my senior year and left. I didn’t know where I was going or why I was going there anymore, and I thought, ‘I’m not going to get a degree that doesn’t mean anything.’ And three years later, I was back on track and focused, ready to go into pre-med again, and by that time, I was living in Canada. I had been living in Vancouver and moved to Ontario because McMaster University was starting a groundbreaking medical school that really focused on the whole person. And I thought, ‘Okay, this sounds like what I’m really interested in.’ And I got there; this is a convoluted story. And I first got a job, place to live, then a job. And then I applied for university. And in Canada, if you’re going to get an honors degree--which is really the prerequisite to going to university--you take thirteen preparatory grades instead of twelve as in the United States. So they looked at my transcripts, and then they took a year for my grade thirteen, and then they took another year because you could only transfer in at the second year, and they said, “Well, if you want to start in pre-med, you’re going to have to go back to your first year.” And I’d done a lot of their prerequisites, but they weren’t accepting the transfer. And I said, “Well, okay. What’s kind of a parallel where I can just get through and do what I need to do?” And I discovered physical anthropology--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: --and I said, “I can do this and I can take the courses I want to alongside of anthropology.” I had no particular engagement in anthropology; it just looked like it had a good parallel to where I was going. And I could continue to take appropriate courses. And so I enrolled in anthropology, as a second-year student in an honors program. And it was physical anthropology at the time, and I went through the program very rapidly, got deeply engaged in anthropology but had not given up my dream of medical school.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And McMaster had this fabulous medical school. I worked full time at the medical center; I was a lab tech. And so, you know, it all made kind of good sense. By the time I finished my undergraduate degree, I was in that program for three years. I was beginning to think that anthropology was making a lot of sense for what I wanted to do, which really was to affect how systems worked and make them work better for people. And it seemed as though anthropology was offering the promise of the ability to do that. By the time I finished my undergraduate, I applied for graduate school in anthropology, even as I was applying for medical school. Some deep ambivalence here, I’d say.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: Got into graduate school and along with my major advisor, helped to develop the first medical anthropology curriculum for my university.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And he made sure that the medical school, the medical center and its associated schools welcomed me to do courses alongside the medical students to enhance a medical anthropology curriculum--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: --a training for me, which was custom built.

VAN WILLIGEN: And where was that?

CRAIN: In Hamilton, Ontario. McMaster University. And this was quite remarkable. They basically--between these two departments--custom built a curriculum--my graduate curriculum for me, so that I could do both a physical anthropology MA but also be taking courses which advanced my medical anthropology training.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: Because it didn’t exist then. And so we put this coursework together for me.

VAN WILLIGEN: So, are you a Canadian or an American?

CRAIN: I’m an American, and I lived in Canada for about eight-and-a-half years. I ended up doing university in Canada. My undergrad--graduate and my graduate university--I abandoned my degree in the United States; I was so done with it. I was over it and started back again in Canada and graduated summa cum laude. I was a university scholar. It was a totally different experience going to school there and when I did; I was obviously ready for it and had a better vision of it. This was a traditional four-fields school.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: We took all four fields, and we were required to be proficient. And even having said that--and it was a very academic school--I was very clear that I had no interest in academic anthropology as a career. I didn’t recognize--at that point--that there was some sort of odd division between the academics and practitioners. They shielded me from that. I came in planning to practice; they nurtured me through my undergraduate and my graduate degree, and then when I said--and I was offered--I was offered a PhD program. I was offered to go to other universities. I was offered a PhD in biochemistry from the lab I worked in, and I said, “No. I’ve done what I need to do. I don’t need a PhD; I’m not going to teach. I’m ready to go.”

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And left. And never, ever did anyone suggest that either my interest in practice or my decision to go out and be a professional anthropologist with an MA was less than a good and proper decision to make. I went back for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the department a few years ago--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And I said, “Thank you. I never knew I was less than. I never knew that this was a bad decision to the world.”

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: “You made me believe, and it gave me great confidence to know, that I was ready.” “And that I could go and change the world if I wanted to.”

VAN WILLIGEN: So it was a four-field, traditional--

CRAIN: Traditional.

VAN WILLIGEN: --quite academic.

CRAIN: Quite academic university.

VAN WILLIGEN: And with no particular advocacy or--

CRAIN: Nothing.

VAN WILLIGEN: Of a negative attitude towards application.

CRAIN: Nothing.

VAN WILLIGEN: It was neutral.

CRAIN: They basically said, “What you decide you want to do is what we’ll support.” And they supported me completely.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. Who are some of the people there that you--

CRAIN: Oh, Ed Glanville was my--and he’s a medical anthropologist--physical anthropologist, was my major, major advisor. Bill Rodman, Pacific specialist. Matt Cooper, who taught me discipline. He taught me discipline in my thinking.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And I say thank you to Matt each and every day. Richard Slobodin was a major professor there. Sid Mead, who is the first chair of Maori studies in New Zealand, He is Maori, was there then. Ruth Landman was at McMaster. Emoke Szathmary.

VAN WILLIGEN: Emoke Szathmary?

CRAIN: Szathmary--

VAN WILLIGEN: Szathmary.

CRAIN: --who ended her career finished her career a couple of years ago as the chancellor of University of Saskatchewan, I believe. And she was an internationally recognized physical anthropologist.

CRAIN: I was at the Triple A, five, ten years ago, and I walked into a session, and there were these young women standing at the back, talking, and I don’t remember exactly what one of them said, but I said--I spun and I said, “So you were one of Emoke’s graduate assistants as well, were you?” Something she said, “And she terrified me, and I admired her so much, but she terrified”--and that’s exactly how I felt. I was one of Emoke’s graduate assistants, and she was a take no prisoners kind of academic and she was brilliant and you damn well better get the job done.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And it was very funny, because she said, “Absolutely.” And I’ve met a couple of other of her graduate assistants over the years--

VAN WILLIGEN: So one of the things that you learn in that context that is really valuable for what you do now is discipline.

CRAIN: Absolutely. Absolutely. Mental discipline, physical discipline as well. I mean, going into the field, whether it’s sitting in an interview or it’s sitting on a mat on the grass, or it’s standing on a street corner for hours--takes a remarkable amount of discipline.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And I’m not sure it’s something we very often talk about but doing it and continuing to be focused having the discipline to gather the information without necessarily [having] regard for your own comfort, safety, yes; comfort, no.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

CRAIN: But also logical discipline. Does it follow? We as qualitative people are constantly bombarded with the idea that what we do isn’t real science--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: It is if we are disciplined about our methods.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. In the primary source form, in your learning discipline about your methods was her?

CRAIN: Matt Cooper was the first one; he taught me undergraduate methods, and Matt had a way of trapping you in logic if you weren’t disciplined about what you were hearing.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: If you bought his first assumption you were dead meat. And he taught me never to buy a first assumption that I wasn’t willing to take home. He taught me to always challenge the logic of what I was seeing and what I was thinking and what I was writing. And to be very certain that my logic was clean. And I talk about a bright line, and I talk about this at the office and I talk about it with students, it has to be a bright line in your logic. It can’t zig-zag.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: --linear logic is important. Cultures may not follow a linear line, but you need to be able to create the logic that strings them all together. And that’s a critical part of our discipline. Emoke just reinforced that.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. When you graduated you just immediately thought in terms of a practitioner career.

CRAIN: Absolutely. I was going to be a practitioner. I was the first, um what was the title? Anthropologist-therapist in a clinical setting in southern Ontario.

VAN WILLIGEN: That was the title. That’s very rare.

CRAIN: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: There are other cases that I’ve heard of but it’s very rare.

CRAIN: And that was in 197--oh, ’75? Seventy-six? I had a background doing counseling and therapy and someone brought me an ad from The Globe and Mail one day and said, “They’re looking for you.” And it was at a regional substance abuse treatment center for Southern Ontario.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And they were looking for an anthropologist with counseling background.

VAN WILLIGEN: And the job was in Toronto?

CRAIN: It was actually at the Chedoke Medical Center, in Hamilton. Which was the regional--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: It wasn’t--you’re thinking of NDRI, which was in Toronto. But that was a research setting. This was a regional-treatment setting. And so as the first anthropologist-therapist, I helped to create the treatment program along with a sociologist and a psychologist and a nurse and it was a remarkable--

VAN WILLIGEN: Right. And that was the actual title?

CRAIN: Anthropologist-therapist.

VAN WILLIGEN: Wow.

CRAIN: Yeah.

VAN WILLIGEN: That’s really unusual. I mean, because there are like almost zero. I mean, it’s not zero, but almost zero that were--

CRAIN: It was one of my prodigal moments.

VAN WILLIGEN: Very few--very few--that’s really interesting. What kinds of things did you do on a day-to-day basis?

CRAIN: Oh. This was absolutely amazing. I mean, the team helped to create the entire therapeutic setting. Once that was done, I was the person who did all cultural assessments.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh. I see.

CRAIN: And what I would do is if someone came in--we dealt with First Canadians; we dealt with Eastern Europeans, all kinds of people who would be in need of specific cultural support. And who might not respond as well as others to the general approach. And so my job was to do all cultural assessments, and the sociologist and I did all intakes. All intake histories. Because part of our job was to screen for special needs such as a cultural special need. And so he and I did all the intake assessments, and they ran two, two-and-a-half hours. They were serious histories.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. I bet they’d be really interesting reading.

CRAIN: It was fascinating. And then if there was a cultural component that we assessed to a client’s treatment, that I would do a cultural assessment, and then I would basically prescribe to the treatment team how this person should be managed through treatment. And I would check in periodically on--they wouldn’t necessarily be assigned to me or to my treatment team--

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

CRAIN: --but I would have, you know, a relationship to the treatment team just to see how it was going. And it was a remarkable position to have because I had dropped out of university the first time being out a little while and then went back, I was a little older than most MA graduates would have been. I was in my late twenties when I did this. And had a strong counseling history.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And then I took extended training through the through the treatment center, so I took greater training while I was at the center.

VAN WILLIGEN: So it was very much a team approach.

CRAIN: Absolutely.

VAN WILLIGEN: And then there were different disciplines represented.

CRAIN: Yes. And my treatment team included a nurse and a social worker, and you know, all treatment teams had three people.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And that way there was always someone to whom a patient could relate or to whom a patient could relate in at any one time. So no one was ever left without someone that they could reach out to, that they knew. This was a thirty-day, inpatient treatment, and then people would go home, but they would be in aftercare for, I think two years. So it was a significant commitment.

VAN WILLIGEN: This was a provincial agency?

CRAIN: Yes. It was a regional treatment center and people came from all over southern Ontario to this treatment center, so it was--

VAN WILLIGEN: But it was supported by the province rather than the--

CRAIN: I’m thinking yes. I left there, but while I was there, I finished my thesis which was on communication patterns in an alcoholic treatment program based on the communications theory. So I was a participant-observer which was very challenging, and finished up my thesis while I was working there. And graduated in ’78. Left Canada, went back to San Francisco where I was first a consultant when I got back? I worked in the San Francisco city and county jails as director of research and evaluation for a prisoners’ health project.

VAN WILLIGEN: So you’re from San Francisco?

CRAIN: I’m from the Bay Area originally, yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And so I worked in the jails for a couple of years and did research and advocacy around prisoner health, and then that project ended, and I did some consulting, and then I became Director of the Indochinese Health Intervention Project, which was a very large translator/interpreter service for incoming refugees into San Francisco, which numbered up to 500 a month at one point. And one year we did 27,000 incidents of service, and I moved up through that system eventually becoming director of refugee services and then associate executive director of Catholic social service in San Francisco. It was a Catholic agency, but it was funded with federal dollars.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. That would be a massive program, it seems to me.

CRAIN: It was huge. It was huge. It was very, very large, and I ran under me were, a health program, an employment program, resettlement programs, English--English access programs, something else. This is a long time ago. And so I was over all of those programs and left San Francisco in ’83, to become director of refugee services for the American Council for Nationality Services in New York.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: They’re voluntary agencies that do all resettlement under a state-department contract basing us with the second largest after the US Catholic Conference. And it is now called something else, and I can’t remember what it’s called. But I was their national director of refugee services. Stayed there a year. By this time Niel and I had already met; we met in San Francisco and decided we really enjoyed working together. I had done some consulting with his agency on the development, and he may have told you about this of a mental health program in Orange County.

VAN WILLIGEN: So you first got to know each other in the context of working on doing one of the projects from his agency.

CRAIN: Actually, Niel came to interview me, because I was providing services to Asian Americans and they were doing a national research project on Asian American health and mental health services.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And so we met when his project he and two of his colleagues came to interview me about what we were doing. We basically knitted together an entire healthcare system for refugees in San Francisco by bringing the best services we could find in San Francisco together. We created the glue. We did all of the appointment making. We did all of the transportation and we did all of the interpreter and translator work and made sure that people got to their appointments, so we supported specialty clinics for maternal and child health pediatrics. Whatever needed to happen we would create with a health organization, a hospital, a clinic. And then my people would basically staff it for them and be the conduit for people into their clinic.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, and this would be in an era where there was little history of doing this and a very rapid increase in the need.

CRAIN: Huge.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, and so there was this splicing things together that made sense and making judgments on the run, basically.

CRAIN: Yes, and we’ve I figured out pretty rapidly that enlightened self-interest rules the world, and there were clinics with capacity and not enough people, and that I had clients with health insurance, and so it was kismet. And it simply took a little entrepreneurial spirit to figure out how to bring that together.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And it worked very well until the federal government decided that they were only going to fund one place for all healthcare for refugees, and that was San Francisco General Hospital. This happened after I had already left, and it was tragic, because--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: --what we were doing was weaving these people into these mainstream services creating an interest in having them in the services instead of leaving them in the one major public health hospital, which really couldn’t support them as well as they needed to be supported, so it was--it was unfortunate.

VAN WILLIGEN: So in relationship to this, it’s always been my perception that the two of you created the firm.

CRAIN: In 1982.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. And so that was done together--

CRAIN: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: --and you met in this encounter, in working on a project together. And is there something prior to the firm that I need to know about? Or any projects, or things of that nature that--

CRAIN: That we did together?

VAN WILLIGEN: I’m not thinking that I’ve gotten up to the point where--

CRAIN: Right.

VAN WILLIGEN: --this joint project started.

CRAIN: Right. Well, what happened was that Niel came to interview me for his study, he interviewed many, many people. And we hit it off, and when his group was asked to come to consult in Orange County on mental health issues for refugees, he asked he had been impressed with what I had been able to weave together in San Francisco for the refugees so he asked me if I would be willing--and my boss said I could moonlight on the weekends. And so for six months, we drove from San Francisco to Orange County--we would spend the weekends there working on the needs assessment, essentially, and then on Mondays we would both go back to our jobs. And at the end of it, we reported out to the refugee groups who had brought us in, and we said, “You certainly could run a wonderful,” you know, “mental health program, except no one’s going to pay for it.”

VAN WILLIGEN: Um-hm.

CRAIN: “They’re defunding mental health services.”

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

CRAIN: So what we helped them to do over the next two years was to create the community resource opportunity project--better known as CROP, which is a community development organization and that was really our first project together under Niel’s organization was that we helped to create this community development organization.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: Community development corporation.

VAN WILLIGEN: And the firm didn’t exist at that point, right?

CRAIN: Didn’t exist.

VAN WILLIGEN: It was probably some sort of prototype for projects, basically.

CRAIN: Yeah. And it was--it was great fun, and at the end of it, we both said, “Well, that was interesting. That was fun.”

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: You know. We were both, I think, getting ready to move on from our current jobs and we said, “Well, why don’t we create a circus? Why don’t we make a consulting firm?”

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. And this might be may be a good time for the three of us to get together.

CRAIN: Yes--

VAN WILLIGEN: And talk.

CRAIN: --that would be good, and the only thing that was separate was that I went onto New York to work for ACNS for a year before I moved to Washington to open our DC office.

VAN WILLIGEN: ACNS.

CRAIN: American Council for Nationality Services--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. Yes.

CRAIN: --which was the big VOLAG. Voluntary agency, I’m sorry. (laughter) No, that’s what they called them. There’s all--there’s all kinds of inside refugee settlement language and the voluntary agencies were called volags, which--when I first started there, I thought it was a Russian social club, you know?

VAN WILLIGEN: Right. And, you might I would be interested in both of your perspectives on where the idea of creating the firm came from. You might even argue. (laughter)

CRAIN: Sometimes we do--

VAN WILLIGEN: Sure.

CRAIN: --so I guess I remember it well.

TASHIMA: Driving up and down California. (laughs) We were helping to design a mental health program for Southeast Asians in Orange County, California.

CRAIN: See, high degree of congruence in our--

VAN WILLIGEN: That’s what I think.

CRAIN: (laughter) It’s good. No prompting.

VAN WILLIGEN: All this, I already knew it. (laughter)

TASHIMA: Yeah, it sort of worked well, and if you can spend what little free time you have in life--driving up and down California--

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh yes, yes, yes, yes. And so you figure it grew out of those conversations.

CRAIN: Oh yeah.

TASHIMA: Um-hm.

CRAIN: We were concerned about the course of development for a number of the refugee communities and the organizations that would serve them and how they were developing and thought perhaps this was an area in which we could be helpful, and so that was really how we founded it. It was a California company. We intended to be in California and to work in California.

VAN WILLIGEN: My perception was always that it was a Washington company (laughter). I went onto with this confusion. I mean, I would get confused about the, what is it, Turlock? And you know, you’d say “They must have taken a project later”--(laughter)--“that put them there,” you know?

CRAIN: There’s a story. And Niel was living in LA. I was living in San Francisco.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And I took the job in New York--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: --because it promised to give us even greater reach and to give me greater training as a professional. While Niel continued on doing our company work, I went to New York to work at ACNS. When I had, I’m being recorded, so I will think about how to say this. (laughter) When it was time to move on--when I determined I was no longer going to do that--we talked, and--and LTG continued to exist, and we determined that the source of so much policy and funding for our clients was Washington, that it would really that it would really be helpful if we had a Washington presence where we could learn more about the process, how policy was made, how funding decisions were made, because our clients were at the distal end of that, and it was clear to us, having both worked on national projects, that being that far away put them at a distinct disadvantage. And so we all agreed that I would go to Washington, DC, and found our Washington office. Within a couple of years, Niel decided--who--he’s originally from the Central Valley. We determined that LA was not a viable place for human beings, and that it was important for people to have a good quality--(laughter)--of life as well as do good work.

VAN WILLIGEN: So Turlock is in the Central Valley?

CRAIN: It’s in the Central Valley.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: Yeah.

TASHIMA: You sort of have a--(laughs) a different quality of life, there. (laughter)

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: The food isn’t as good as San Francisco, but, you know.

TASHIMA: That’s true.

CRAIN: What are you going to do?

TASHIMA: But you can now afford a house if you got any money left--

VAN WILLIGEN: Sure.

TASHIMA: --and, if you come with a job, you’re in really good shape. But the county--we’re in Stanislaus County--has the second- or third-highest foreclosure rate in the country, and, I think unemployment’s running around eighteen percent.

VAN WILLIGEN: Wow.

TASHIMA: Yeah, at one point it was up to twenty-five percent.

CRAIN: But Niel moved--Niel moved the LA office out into the Central Valley, and I established the Washington, DC, office. And again, we weren’t--we were in Washington in order to learn not to become a federal contractor.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: Niel continued to lead our refugee work in California driving tens of thousands of miles a year up and down the state of California to work with our refugee clients many of whom were we worked with model organizations. We worked with southeast Asian general organizations. We worked with county organizations working with refugees, so it was a remarkable amount of focus on some small organizations.

VAN WILLIGEN: Did you develop early in the process a business plan, consciously? And, (laughter)--

TASHIMA: Well, we--

CRAIN: Yes, we did. (laughter) We did.

TASHIMA: And we continue to develop business plans. It’s part of our--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yeah, I actually--(laughter)--I know that ideas just emerge and then you--often people later on the developer will rationalize the model for it.

CRAIN: Well, there was some of that, too. Yeah. (laughter) But in Washington one of the things that happened was that we began to serve refugee organizations and refugee serving organizations in the metropolitan DC area and so we were really then in two areas, doing roughly parallel work with refugee organizations. We expanded to working with Ethiopians. We did a national listening tour with Ethiopian leadership across the United States to find out what Ethiopian refugees needed across the country. That was a six-country--six-country--just seemed like countries, you know? Six--

TASHIMA: Well, at that point they could have been different countries. (laughs)

CRAIN: --state listening tour with--with Ethiopian leadership helping them to set this up and facilitate it. We began to work in other states with refugee projects. We ended up doing a lot of work in Texas at one point on refugee issues, many, many Texas cities.

VAN WILLIGEN: And did you have any models for your firm that were important in your planning at all?

CRAIN: Anthropologically based--other anthropologically based firms? No.

VAN WILLIGEN: I don’t think there, they’re rare, I mean.

TASHIMA: (laughter) One of our colleagues in San Francisco started doing this, you know, “We’re not anthropologists.” So we’re committing professional suicide. (laughter)

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: Yet we had good jobs--

CRAIN: Yes.

TASHIMA: --doing the kinds of work we were doing, and networks that reinforced this and you knew how to get funding to bring things together and make things happen. And we sort of walked away from that and said, “There are needs we can’t address by being in these kinds of contexts.” So if we created our own firm, we can go and do things that are actually compelling. Because it’s a challenge every day to do this. They provide services and resources in places that don’t have them and anthropology as a resource is a very rare commodity at the moment, and particularly in Central California where we started, it was nonexistent money. There are universities around--and we did thoughtful reaching out to them and trying to engage them and discovered this wasn’t what they saw themselves as doing, which is what many universities do, and that’s fine.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

TASHIMA: We just didn’t want to walk into someplace somebody was already doing things and say, “Hey, we’ve set up shop. We’re better than you are.” But we did a very thoughtful process--we went through a very thoughtful process, and we continue to do this with local universities.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

TASHIMA: And so it’s been interesting finding this niche that we see as our business but nobody else is really being interested in doing much about it in the Central Valley. The Central Valley LPO has started to do that, and that’s really nice to see. But again, the kinds of things we do where you do anthropology every day is not something people see as a business.

CRAIN: Yeah. And it was interesting, because over the period of time we’re talking about was--I went to DC in ’84. And from ’84 to ’87 is basically the period we’re taking about, where almost all our work was refugee focused. And there’s a Y in the road that happened in ’87.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And we received--we were responding to (laughter) an ad to do some team teaching, and--

TASHIMA: Well, we wanted to turn it into a team-teaching seminar. (laughs)

CRAIN: They were looking for somebody to teach refugee resettlement at Cal State University, Long Beach, and because Niel was--you know, in LA, we thought he could teach it most of the time and then when I flew in, we could team teach. And so we responded to this ad and we got an interview. And I do not remember who it was--this was long before Bob Harmon was…

TASHIMA: Chair.

CRAIN: --chair in 1987, and we were talking with the chair. Nice woman. And in the middle of our conversation--she was talking about what we had done, what kind of experience we both had--and in the middle of it, she sprang out of her chair and said, “Wait here.” And ran from the room. And we sort of looked at each other and we thought, ‘What did we do wrong?’ (laughs) And she was gone for like, fifteen or twenty minutes. And she came back with this man in tow --and she said, “You all need to know each other.” And we said, “Okay.” Well, it turned out that Cal State had a cooperative agreement with the CDC to do HIV/AIDS prevention work in Southern California.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And that they had to do an ethnography they had to reach out to sex workers and they’d had a difficult time doing that. And they said, “Could you do that?” And we said, “Sure. We can do that.” But--you know, we’re anthropologists. (laughter) We can find anybody. And they said, “Well, can you send us within the next week how you would do this?” And we said, “Sure, we can do that.” And we went away, and we were driving up the state of California starting the next day, and we looked at each other and we said, “Sure we can do that?” (laughter) And what we did as we went up the state was we had a laptop, and we took turns, and we created a method that would allow an organization to systematically move out into a community to understand who they are, what their needs were, what their beliefs were. Over the next six months, we interviewed--this is—“we” writ large, because we had a team that we trained--335 out of treatment IV, drug users and others. And basically showed--turned out a picture to Cal State and through them to the CDC, of what the population of drug users looked like in Long Beach, California. And it was a nuanced, complex, interesting picture that started with the people who serve IV drugs users. It was IV and other drug users. And we--we simply moved out from there through systems and networks to create this network and to bring people in to interview them. And CDC saw this and asked if we would tailor our method for their cooperative agreements, and so we were brought into CDC and the method is called the community identification method, or CID which has been used since 1987 as part of CDC’s formative methods, and is part of what’s called an EBI-DEBI, an evidence-based intervention. There’s a rigorous process by which something becomes an evidence-based intervention, and CID is part of an evidence-based intervention.

VAN WILLIGEN: I heard you say “EBI-DEBI”?

CRAIN: Right. EBI is evidence-based intervention. DEBI is diffusion of evidence-based interventions. So CDC sets about diffusing these methods so that their grantees and others are using evidence-based methods.

VAN WILLIGEN: And this was the first project of the firm? Or the project of the firm that--

CRAIN: It was the one--

VAN WILLIGEN: --project that led to the development--

CRAIN: No, it was.

TASHIMA: (laughs) It--after that--

CRAIN: --1987, and we’d been working together since ’82.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: Actually since ’80/’81. But it was the Y in the road. We had only been doing refugee work up to that point--

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, I see.

CRAIN: --and it was the project that took us out of refugee work--it took us to a national audience, to a national arena, it launched us to working with the federal government, it was really a seminal project for us, and we need to acknowledge that the person who brought us into the CDC was an anthropologist.

TASHIMA: I think the only anthropologist on staff in Atlanta at the time.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

TASHIMA: And the refugee work we did, there were very few people doing it at the level we were working at that point in terms of anthropology. There were maybe ten, twelve people--

CRAIN: Yeah.

TASHIMA: And we all knew each other.

CRAIN: We all knew each other. Peter Van Arsdale was one.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh yes.

CRAIN: And [Dwight Reining?] was another.

TASHIMA: [Reining] was another.

CRAIN: There were a dozen of us maybe.

TASHIMA: And we knew all seeing each other, at meetings and compare notes--

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

TASHIMA: --but that was sort of the first thing we did as a firm. And it was a major policy and service issue. How do you work with people that are sort of dropped into the context of the US with no experience? What do you have to do and how do you have to work with them?

CRAIN: Yeah.

TASHIMA: HIV became the second thing we did as a major policy impact. Because in 1987/’88, CDC discovered that they didn’t know enough about people at risk for HIV and were trying to figure out how you do this, so they funded eight cooperative agreements around the country to start looking at this, and all eight projects ran into the same problem. They could design what they thought were great public campaigns and put stuff out there in their clinics, but people didn’t use them. And they didn’t know how to make that step out of the clinic. And the method that we had created for this IV drug study in Long Beach came to their vision because this was part of that cooperative agreement, and Kevin O’Reilly, the chief of the section saw this and said, “This could work.” So he had us come and train his eight cooperative agreement grantees in this method--

CRAIN: And that was a cohort of cooperative agreements that was focused on gay men. Largely on gay men at that point.

TASHIMA: And as we trained them in this method, it did some fascinating things. One, it compelled them to use a consistent method and grantees don’t do things consistently. They have their own best idea, but CDC said, “Because you’re a cooperative agreement, you will do this.” And we brought them all together for a four-day training and said, “Here’s how we’ll do it.” CDC then funded us to go on site and provide TA but also to provide quality control of the application of method. So all eight of these sites now spoke the same research language, which was heavily influenced by anthropology and had oversight from the two of us about how they did these, from how you go out and interview somebody to how you bring your data and put together what you do with it. And we read--

CRAIN: Hundreds.

TASHIMA: --hundreds of interviews, because we were giving them constant feedback about how their interviewers were doing in the field. This is debriefing them. And then when they start analysis, we would go to each site, work with them for two or three days, looking at their data, and doing analysis on this. So you had a great deal of consistency from one site to another.

CRAIN: And then there were, I think, three more cohorts that CDC brought us back and asked us to train and do the same kind of support to, including data analysis and so you had this cadre of organizations then, who were using a standardized method to do their formative research about their populations of concern. And it really, I don’t know if you know Claire Sterk Elifson?

VAN WILLIGEN: No.

CRAIN: Claire was brought into CDC, after we had started. Niel and I and Claire and Kevin O’Reilly ended up writing the research method up and publishing it, and it’s in the literature--this entire method. CDC then took it and continued to disseminate it through their channels and through their trainings, and their training centers now train on the CID method.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And STDs picked it up, and STD programs use it as their formative method. It is as Niel said, a heavily-anthropologically informed method which is intended to respectfully reach into communities and ask them to share what’s important about those communities and their risk with researchers. It really demands that the researchers understand the context in which people live and the assumptions and culture under which they operate. It was very insidious.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes, there’s always been a problem with ethnographic field methods about the comparability from site to site.

CRAIN: Yes. Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: And so, the important innovation that occurred in the realm of research and practice was some mechanism by which comparable data could be prepared using methods that tended to generate data that weren’t comparable.

CRAIN: Yep.

TASHIMA: One of the really fun and fascinating things that came out of the first round that we did, we were doing analysis and we had piles of interviews, doing our old-fashioned pile sorts. At one point, one of us looked at the other and said, “Are you seeing a pattern of how people are related?”

CRAIN: Oh, this was pre-IRB days and we asked people to give us their first name. You know, we didn’t ask for their full name, but we wanted to be able to say, “Jane’s interview.”

TASHIMA: Street names.

CRAIN: Well, and we asked for street names, too.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yeah.

CRAIN: But we wanted to be able to say, “This is in--Jane interview.” Or “This was Ralph interview.” Whatever.

TASHIMA: But part of the protocol was a chronology of what people do--

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: So we’d ask you, “What time did you get up in the morning?” And work all the way through their day to the time they went to bed. And then, “What did you do three days ago?” And then, “What did you do last weekend?” And so you have this interesting slice of life from people. Now these are all active IV drug users and the PI said, “Drug users won’t remember anything, and there’s no way you’re going to know if this is accurate.” We said, “Well, trust us. This’ll work.” And these--some of these people were shooting a lot of heroin at that point.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: But we went through this, and one of the things that became remarkable was what they watched on television. And this was in the LA Basin, and the Olympics were going on. And people were giving us scores, times of trials, and who was winning and what was going on. “Oh, I saw this yesterday.” They were--they were also a lot of them watching PBS, and they would tell us what program was on at that night. So you had real markers of things--(laughter)--in the real world that you could objectively go back to, you know, playlists or TV Guide and see.

CRAIN: One of the things we asked people was, “Who do you trust for information?” And we would get names. And we would ask them, “Who do you hang out with?” Again, we didn’t want last names. We wanted to know who they hung out with, because this was triangulating networks and trust and how information moved through networks, and we would debrief with our field researchers and we would take their interviews, and we would--we would run analysis on them. And as Niel was saying, one day we were crawling around on the floor in these piles of information, and we both began seeing patterns of people crossing over. Street names are generally pretty particular. So, you know, Stinky Feet and saw Ralph the Mooch every third day. And they would cross-reference one another. And we began doing this giant network analysis and what we discovered was that there were clear paths for information transfer among trusted resources. And we also found that the people being sent to be interviewed, or the people who we were interviewing, were being referenced across networks, and it created this--this enormous network, and one of our reportings to the project and to CDC was that you have nodes or trusted people into whom you can put good information and that information will go out through the network, and it will be trusted information. And using this is going to speed your plow a great deal.

TASHIMA: Yes, and the information will maintain its integrity as it’s spread.

CRAIN: Yep. Yep.

TASHIMA: We hoped. (laughter)

CRAIN: So that was the project, and then we did, I guess four cohorts for CDC of training, support, and analysis, and CDC adopted our method which really carried us into the HIV/AIDS realm. We did some research beyond that. We did site visiting beyond that for CDC. We did tuberculosis research, behavioral research for CDC. We did hepatitis research for the CDC. We did a lot of work for the CDC. This really launched us into federal work in healthcare. Since that time, we’ve worked with Health Resources and Services Administration looking at--

TASHIMA: All kinds of stuff.

CRAIN: (laughs) All kinds of stuff. Geriatric program services. We’ve looked at homeless issues. We’ve worked on food security, we’ve worked on rural health issues. We’ve worked on HIV/AIDS in HRSA. Uh, we worked on genetics education. The list is pretty extensive.

VAN WILLIGEN: All in the context of the firm.

CRAIN: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: And one thing I’ve never been totally clear on, and that’s how the firm was- what kind of an organization it was legally, it could be a corporation; it could be a--

CRAIN: We incorporated in 1984. We were a partnership for two years, and then we incorporated in the state of California where we’re a closely held corporation--

VAN WILLIGEN: I see.

CRAIN: And we are to this day a closely held corporation. Niel and I are majority shareholders. Closely held simply means that there are only a few shareholders.

VAN WILLIGEN: And then the title that I’ve seen, the “managing partner” relates to the legal status of--

CRAIN: No, we made that up.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, okay. (laughs)

CRAIN: No, we were trying to figure out what would convey information about what we do. And we’re partners, first and foremost. And so, being called “the partners” seemed a little pretentious, and “partner and partner” seemed strange. But then we also managed the company. And so it just sort of evolved into “managing partners”and fairly early on, as I remember.

TASHIMA: You sort of make things up and it sounds real. You print a lot of business cards, and then it is real.

VAN WILLIGEN: (laughs) Yep, that’s right.

CRAIN: But it works, because people now understand that we are the partners, but we’re the managing partners. And I suppose that allows for the opportunity that there could be other partners someday.

TASHIMA: Yeah, they could give us money to become partners. (laughter) One of the interesting things, and this is a question you asked a while back about business and how we structured this. Somewhere in the early ’90s, as we were getting into federal contracting, we figured out that if you became an 8(a) small business. You got preferential contracting opportunities with the federal government. And so the 8(a) program a set-aside program for minority-owned businesses. But you had to structure yourself in a certain way. And so we set about doing this and it focused us on the business side of this enterprise. Right, if you didn’t think about this [inaudible], you get money and you write checks and you sort of just keep this all moving. In becoming an 8(a) firm, you go through a certification process, and your business practices are part of what they review and so we had to sharpen the business side of what we did. And we had to do projections--cash flow projections. We had to have the necessary resources skill sets around us in order to run a business. So we had to go find attorneys. We had to find bankers. We had to find CPAs. You know, all of these people--these high-power, legitimate degrees that we knew nothing about.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. (laughter)

TASHIMA: In working with Small Business Administration, they really helped us understand this. They did a really nice job, we worked with the Fresno office those folks were great.

VAN WILLIGEN: You said it’s an 8(a) .

CRAIN: It’s part of the Small Business Administration.

VAN WILLIGEN: Oh, that must be a section of a law.

CRAIN: It’s a section of a law, the small business act, and 8(a)s are this class of minority-owned firms, and there is a waiver of some of the competitive requirements because the belief is and it’s an entirely legitimate belief that small businesses and particularly minority-owned small businesses run at a disadvantage to large, majority-owned businesses in competition for federal contracts. And so it gave us a preferential, competitive place. And we were certified in 1991as an 8(a) firm.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

CRAIN: And I know this because there’s--(laughter)--there is a time limit on how long you can be an 8(a), and we graduated from the program in 2000. And we competed for and won two very large international contracts as we were graduating from the program. And anything you have before you leave the program, you take with you. So we graduated with some and one of the challenges is to continue out into the competitive arena; it’s very difficult, and a lot of small firms fail. I don’t know about your anthropology program, but ours didn’t teach much about business or business competition. All of those things.

TASHIMA: The general sense within the business community is that a small business or a startup firm--if it makes it past its fifth year, it has a good chance. But something like sixty or seventy percent fail before they’re five years old.

CRAIN: Yeah.

VAN WILLIGEN: Right.

TASHIMA: And so there’s that hurdle. And the SBA world of 8(a) programs, you could set out doing anything, but the idea was that sooner or later, you would become a telecommunications company. And this was the goal everybody was supposed to have and like, “Oh no,” and this the 8(a)--the SBA people we worked with--it took them three or four years to understand what in the world we actually did. (laughter) It wasn’t that they understood that it was, “Okay, you’re not going to become a telecommunications firm. You’re going to continue to do what you’re doing.” And so they kept talking with us about how this would be a viable business plan or, “I don’t know,” you know. You do these projections, and you hope for the best. But it meant that we had to project three to five years out--income, expenses, all kinds of stuff. And show them why these were sort of realistic guesses. And one thing I walked away from all this was that budgets are estimates.

[Pause in recording]

VAN WILLIGEN: It’s now on.

TASHIMA: And we learned a great deal from SBA, and this is not stuff I wanted to know. I still don’t want to know this, but in order to be effective with them, we needed to learn their language and the culture of being a businessperson. And so we set about doing this. And over the years--we’ve gotten pretty good at doing all the things a business is supposed to do, but I think the important lesson was trust your advisors, so your accountants or people that say, “Don’t do that. Don’t spend your money that way. Put it over here, because you’ve got to do this for that.” And you’ve got to listen to them. Our attorneys advise us on all kinds of stuff, and we don’t need them nearly--we don’t use them nearly as much now as we used to when we were getting going, but at the beginning, we were in regular communication with three different sets of attorneys with different things. And you have to pay them for their time. (laughs)

CRAIN: Yes.

VAN WILLIGEN: It’s pretty expensive, too.

CRAIN: It’s very expensive. But as Niel said, one of the things we are really clear about is that if we’re going to run a business, it’s going to be a good business and we are going to be able to sleep at night without worrying and we’re going to be able to leave for weeks at a time when we travel internationally without worrying that a system is going to implode.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: So we’ve really invested in our management systems; we’ve invested in having human resources for our company, having a top-notch accounting and invoicing system . You know, it was an investment, but it has made it so much simpler for us to be anthropologists at the end of the day. Rather than rushing around trying to figure out what was going to fall apart next, which I think is too often the result of a casual approach to business. And it’s something that we’ve grown into. In 1983, if you’d talked to us about this, we would have sounded quite different. But we’re twenty-nine years old as of two months ago.

VAN WILLIGEN: I see. That’s quite impressive.

CRAIN: We are twenty-nine years old.

VAN WILLIGEN: And what did you say? Six years? Or--

TASHIMA: Yeah. Five years--

VAN WILLIGEN: Five years.

TASHIMA: --and sixty, seventy percent go belly up. And over the years, we’ve watched colleagues and competitors--not anthropologically based firms, but other firms do that. They start with a great idea and they pull in a major contract or several good-sized contracts, and that next jump is really hard.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

TASHIMA: You get comfortable. You don’t think about, “Oh, okay, I’ve got to be developing something new, or somebody has to be paying attention to that.” Or at the end of these contracts, you’re--there’s nothing coming in again. And nobody’s going to help you do that.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. So it’s the same thing, the cash flow, I guess.

CRAIN: Yes.

TASHIMA: Yeah, having that next contract, and it’s one of the real challenges of this and one of the real drawbacks of this is you’re always trying to figure out what’s next. How do we keep this infrastructure going because somebody’s got to pay the bills, somebody has to pay everybody and that means somebody’s got to be looking two-to-five years ahead of us. And guesstimating where the federal government’s going to go, where the foundations are going--

CRAIN: Yes. Yes.

TASHIMA: --what social issues are going to move to the front of the line, how we use anthropology to address those kinds of things--

CRAIN: And it’s interesting, because we’re working on this praxis reflection for tomorrow. And it’s really been an interesting reflection, I think, for me. We’ve been generalists. We site ourselves in health and human services, but we’ve been willing to go where there have been opportunities to make change. One of the challenges is that systems become set and when they are, it’s much more difficult to find a point of leverage and they’re much less interested in innovation.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: And one of the brilliant things that happened with at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic was that; and this was reflective of what had gone on in the refugee services world, was that because this was an emergency, systems were open to innovation, and it was a brilliant moment to be able to bring the goodness of anthropology--and it wasn’t just us, I mean, there were--as I say--there were other anthropologists who were busily at this. Merrill Singer has been around for years doing HIV/AIDS work, Kevin O’Reilly, who’s now with the World Health Organization. Claire Sterk Elifson. There were others who were there at that moment when there was an opportunity to help systems to be creative and accessible, and innovate, and then they slowly settle. We’ve been at that point for a number of issues, and it’s not entrepreneurial what we do so much as it’s trying to see where we can have a point of leverage to use our skills in a way that’s going to have meaning, and so talking about being generalists is kind of a misnomer. We go where we see potential, and sometimes that’s serendipity and sometimes it’s the result of good planning. (laughs) There’s probably equal parts.Over the years we’ve gotten people to know us, and so we get people coming to find us, which is really wonderful.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes.

CRAIN: We also continue to have to market what we do to people who have no idea what an anthropologist is. We talk about ourselves on our website as an anthropologically based consulting firm. It narrows the people who are going to respond, “Oh yes, I know what that means,” affirmatively. But it is our definition of ourselves.

VAN WILLIGEN: Yes. I noticed that when I reviewed the website. And it led me to the conclusion that it wasn’t just another consulting firm and had a special orientation and I was wondering if you could comment on the way I expressed it in my notes, it was something about the ideology of the firm and I mean there would be different ways of saying that, but there was a certain viewpoint, a certain kind of mission statement. You might want to comment on the important themes in the firm’s view.