An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Solar Commons: An Arts and Engineering-Integrated Project of Applied Anthropology for a Just Energy Transition

Dr. Kathryn Milun

Associate Professor of Anthropology and Fellow

University of Minnesota’s MN Design Center

In 2023, an anthropology & engineering solar project won first place in the US Department of Energy’s US Solar District Cup Collegiate Competition. The “Solar Commons Team” of anthropology undergraduates at University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD) and engineering seniors at University of Minnesota Twin Cities campuses won first place nationally with their design for UM campuses to share the financial benefits of their rooftop solar arrays with tribes on whose ancestral lands Minnesota’s five campuses are sited. (Figure 1) Students took examples of local, village-scale energy sharing from peat and forest commons and applied this customary law concept to solar infrastructure and state efforts towards a just energy transition. Minnesota mandates that by 2030 government buildings install rooftop solar to meet three percent of their electric load. Students designed a 3MW solar array with a 500kW “carve out” that would, at no cost to the university, create approximately $68,000 of solar savings a year for a community trust fund. Students proposed that such “Solar Commons Trusts” could be set up for each solarized campus. Campuses would have Solar Commons digital dashboards in their libraries showing the real time solar savings and long-term flow of the sun’s common wealth value to reparative justice work. Students’ plan included additional public art that made visible these flows of value. Innovating the legal strategies allowed by trusts, students of legal anthropology designed a process for an otherwise passive community trust beneficiary to become the active designer of the trust’s Indigenized purpose.

In 2023, an anthropology & engineering solar project won first place in the US Department of Energy’s US Solar District Cup Collegiate Competition. The “Solar Commons Team” of anthropology undergraduates at University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD) and engineering seniors at University of Minnesota Twin Cities campuses won first place nationally with their design for UM campuses to share the financial benefits of their rooftop solar arrays with tribes on whose ancestral lands Minnesota’s five campuses are sited. (Figure 1) Students took examples of local, village-scale energy sharing from peat and forest commons and applied this customary law concept to solar infrastructure and state efforts towards a just energy transition. Minnesota mandates that by 2030 government buildings install rooftop solar to meet three percent of their electric load. Students designed a 3MW solar array with a 500kW “carve out” that would, at no cost to the university, create approximately $68,000 of solar savings a year for a community trust fund. Students proposed that such “Solar Commons Trusts” could be set up for each solarized campus. Campuses would have Solar Commons digital dashboards in their libraries showing the real time solar savings and long-term flow of the sun’s common wealth value to reparative justice work. Students’ plan included additional public art that made visible these flows of value. Innovating the legal strategies allowed by trusts, students of legal anthropology designed a process for an otherwise passive community trust beneficiary to become the active designer of the trust’s Indigenized purpose.

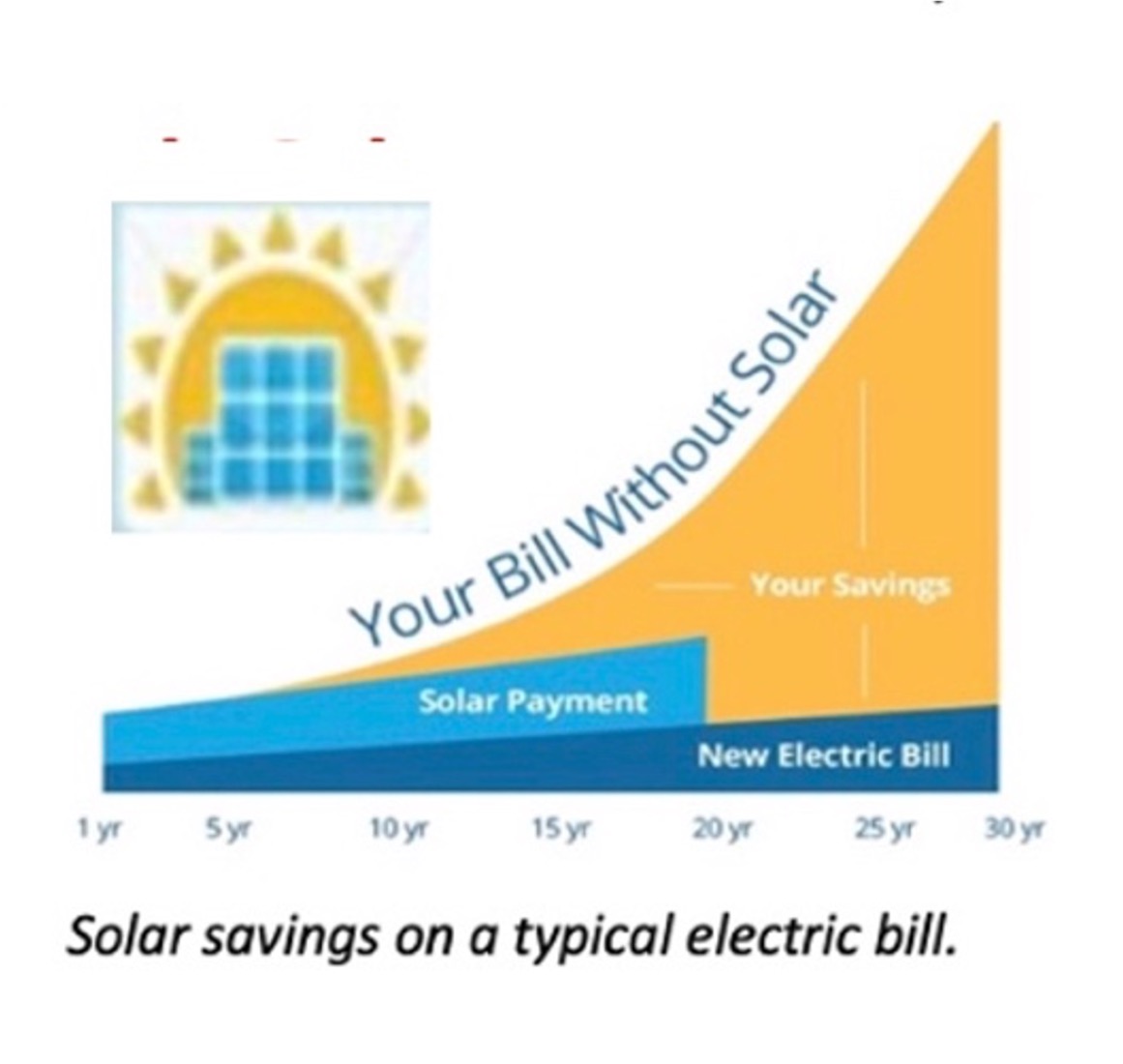

The founder and director of the University of Minnesota’s Solar Commons Research Project, Anthropology Professor Kathryn Milun, will be speaking about this project at the Society for Applied Anthropology meeting in March 2024. Dr. Milun works in collaboration with UM’s Endowed Chair in Renewable Energy, Mechanical Engineering Professor Uwe Kortshagen as well as Professor Ellen McMahon, Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the University of Arizona’s College of Fine Arts. Solar Commons is a work of applied legal anthropology and arts-integrated engineering. With the calculations of engineers, the imagination of artists, and the place-based knowledge of community members, anthropologists can turn the magical invisibility and hidden wealth of our energy infrastructure into locally managed and beloved community economies. Solar Commons is an alternative and a challenge to what is emerging as the common sense of green neoliberal solar energy. How much financial value is actually present in a solar photovoltaic array? (Figure 2) Through social rules and solar hardware and software design, Solar Commons can transform solar’s market value into community-owned common wealth.

The founder and director of the University of Minnesota’s Solar Commons Research Project, Anthropology Professor Kathryn Milun, will be speaking about this project at the Society for Applied Anthropology meeting in March 2024. Dr. Milun works in collaboration with UM’s Endowed Chair in Renewable Energy, Mechanical Engineering Professor Uwe Kortshagen as well as Professor Ellen McMahon, Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the University of Arizona’s College of Fine Arts. Solar Commons is a work of applied legal anthropology and arts-integrated engineering. With the calculations of engineers, the imagination of artists, and the place-based knowledge of community members, anthropologists can turn the magical invisibility and hidden wealth of our energy infrastructure into locally managed and beloved community economies. Solar Commons is an alternative and a challenge to what is emerging as the common sense of green neoliberal solar energy. How much financial value is actually present in a solar photovoltaic array? (Figure 2) Through social rules and solar hardware and software design, Solar Commons can transform solar’s market value into community-owned common wealth.

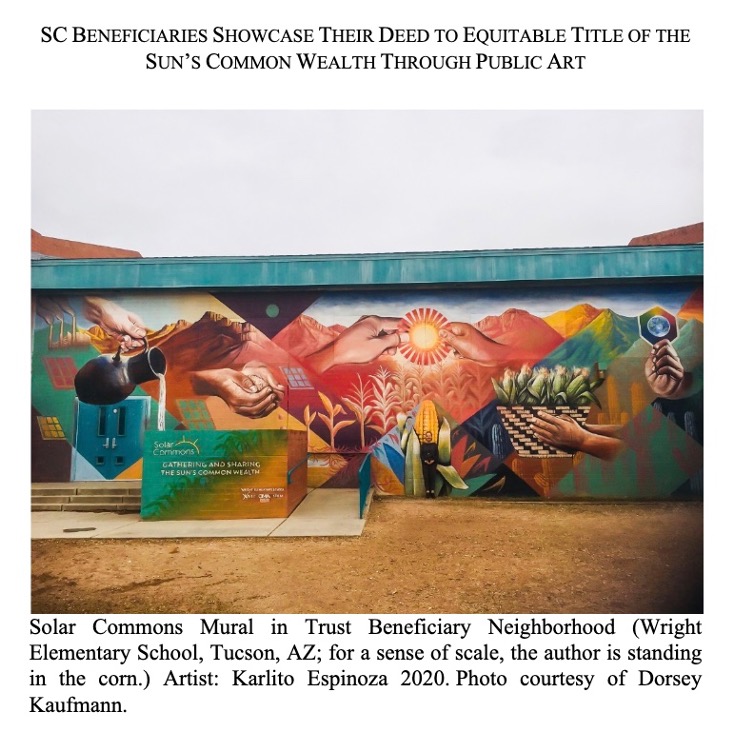

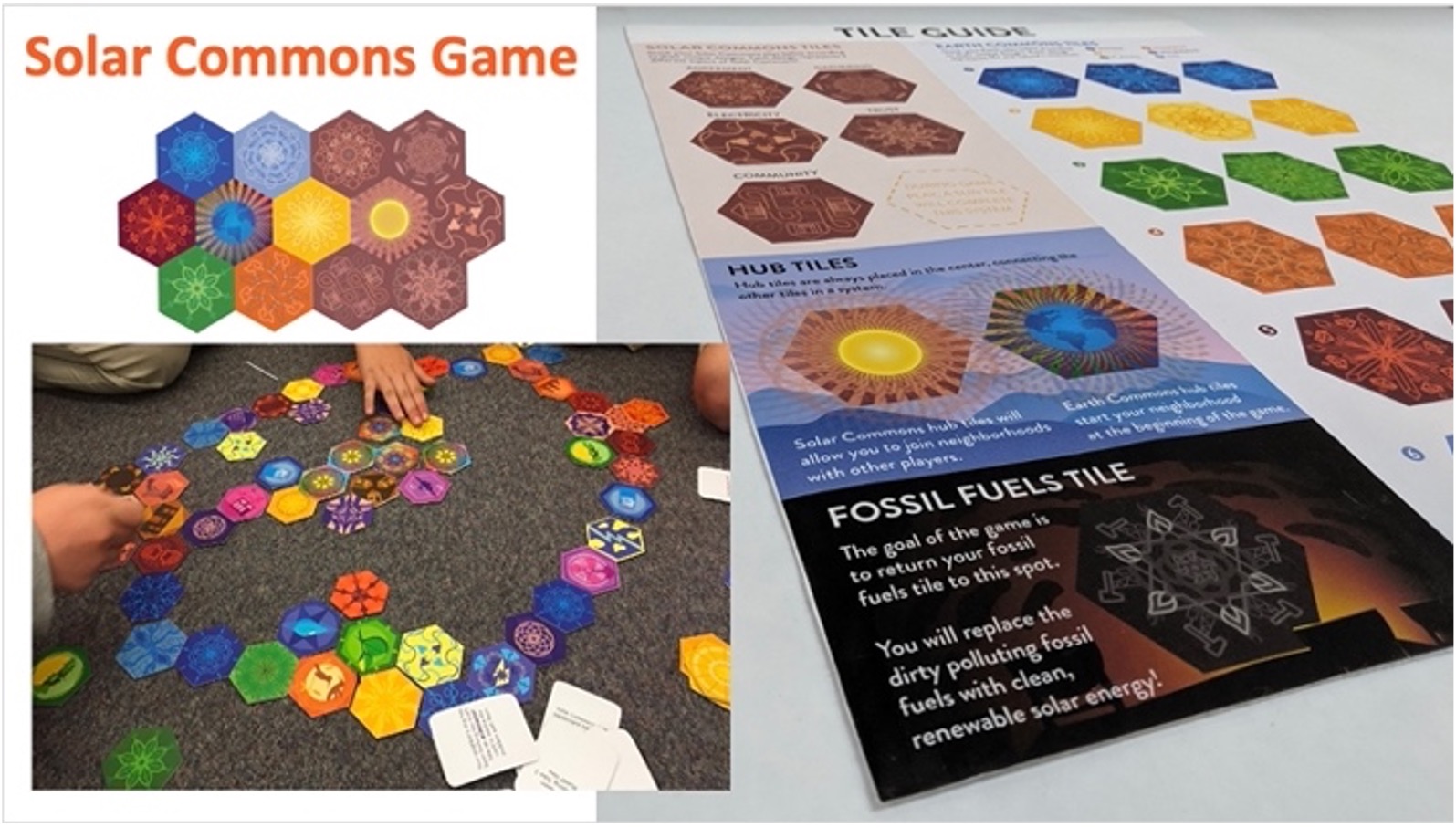

The first Solar Commons was connected to the electric grid in 2018 in Tucson, Arizona. This first SC prototype is a 14.5kW system that generates around $2,500 a year for its trust beneficiary. In 2020, a community-collaborative public art mural (Figure 3) was painted by University of Arizona art students on the schoolyard wall of the elementary school in the Tucson trust beneficiary neighborhood. There are twenty-six languages spoken in this low-income neighborhood, a center for political refugees. The mural is the neighborhood’s claim to their share of the sun’s common wealth. Art students who worked on the mural also designed a beautiful tile board “Solar Commons Game” that the schoolkids play to learn about reciprocity, the heart of “commoning.” Through fun scenario-cards and mosaic tile placement, kids learn how to share through “solar commoning.” They learn how the ecological world shares through “nature commoning.” (Figure 4). After playing the Solar Commons game, kids engage in a participatory budgeting process. (Figure 5) They keep the game’s guiding principles of reciprocity in mind as they deliberate about what might be done or built in their neighborhood that year with the annual disbursement of the sun’s common wealth. The school will vote on an appropriate project and use their Solar Commons funds to pay for it. Once the project is completed, the kids will take pictures and upload them on their community-facing digital dashboard. This peer governance dashboard will provide transparency, accountability, and historical record of how the Solar Commons funds are spent in their neighborhood.

The first Solar Commons was connected to the electric grid in 2018 in Tucson, Arizona. This first SC prototype is a 14.5kW system that generates around $2,500 a year for its trust beneficiary. In 2020, a community-collaborative public art mural (Figure 3) was painted by University of Arizona art students on the schoolyard wall of the elementary school in the Tucson trust beneficiary neighborhood. There are twenty-six languages spoken in this low-income neighborhood, a center for political refugees. The mural is the neighborhood’s claim to their share of the sun’s common wealth. Art students who worked on the mural also designed a beautiful tile board “Solar Commons Game” that the schoolkids play to learn about reciprocity, the heart of “commoning.” Through fun scenario-cards and mosaic tile placement, kids learn how to share through “solar commoning.” They learn how the ecological world shares through “nature commoning.” (Figure 4). After playing the Solar Commons game, kids engage in a participatory budgeting process. (Figure 5) They keep the game’s guiding principles of reciprocity in mind as they deliberate about what might be done or built in their neighborhood that year with the annual disbursement of the sun’s common wealth. The school will vote on an appropriate project and use their Solar Commons funds to pay for it. Once the project is completed, the kids will take pictures and upload them on their community-facing digital dashboard. This peer governance dashboard will provide transparency, accountability, and historical record of how the Solar Commons funds are spent in their neighborhood.

The Solar Commons Research Project (SCRP) is located at the University of Minnesota’s MN Design Center. Arts direction for the project comes from the University of Arizona School of Art. The aim of this community-university collaboration is to produce a set of free, open source tools—legal agreements (with graphic art versions); digital solar dashboard platforms that create transparency, accountability, and common wealth visibility for all solar commoning parties; and finally, community curriculum that engage local artists to work with solar commoning communities using the game and participatory budgeting to distribute the sun’s common wealth. This arts-integrated form of community trust solar ownership includes process steps for each solar commoning community to co-design their publicly facing mural that stands as their “deed of equitable title” to the sun’s long-term promise of common wealth.

The Solar Commons Research Project (SCRP) is located at the University of Minnesota’s MN Design Center. Arts direction for the project comes from the University of Arizona School of Art. The aim of this community-university collaboration is to produce a set of free, open source tools—legal agreements (with graphic art versions); digital solar dashboard platforms that create transparency, accountability, and common wealth visibility for all solar commoning parties; and finally, community curriculum that engage local artists to work with solar commoning communities using the game and participatory budgeting to distribute the sun’s common wealth. This arts-integrated form of community trust solar ownership includes process steps for each solar commoning community to co-design their publicly facing mural that stands as their “deed of equitable title” to the sun’s long-term promise of common wealth.

The arts-based Solar Commons toolkit would be useable in many locations. Solar Commons researchers envision their community trust-owned model of community solar iterating around the US. Indeed, when the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) analyzed the financial model and scalability of the small Arizona SC project, it saw a potential US iteration of Solar Commons to at least ten gigawatts over the coming decade. This represents enormous benefits of solar, billions of dollars, staying local and flowing to underserved communities. But RMI also recommended that a single Solar Commons not exceed the 500kW size (Brehm & Lillis). Up to the 500kW scale, a Solar Commons project, they found, has a positive net present value. Meaning, at that size, the costs of the solar hardware remains significantly less than the amount of money that will flow out to a community beneficiary over the decades. Solar Commons up to 500kW are a great investment. A donor wanting to mitigate climate change and support community wealth building in low-income neighborhoods would feel confident in funding a Solar Commons array. A good corporate neighbor with a flat, big box store or factory roof could install a solar system and use the Solar Commons toolkit to pass their electric bill savings on to underserved rural or urban neighbors. City, county, state and federal entities who want to decarbonize their buildings can invest in up to 500kWs of solar, pay off the costs of the system from a few years of solar savings, and then pass on the savings from remaining years to a community trust. Public entities can thus support a more vibrant, grassroots democracy by sharing these common wealth trust funds with community groups and schools who will use the tools of solar commoning to thoughtfully deliberate, budget, vote and follow up on the use of their neighborhood dollars. Schools and neighborhood groups would learn basic guiding principles of commons—reciprocity, social equity, mutual aid and benefit—and celebrate yearly events in which common wealth trust funds were dispersed to local community projects.

The arts-based Solar Commons toolkit would be useable in many locations. Solar Commons researchers envision their community trust-owned model of community solar iterating around the US. Indeed, when the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) analyzed the financial model and scalability of the small Arizona SC project, it saw a potential US iteration of Solar Commons to at least ten gigawatts over the coming decade. This represents enormous benefits of solar, billions of dollars, staying local and flowing to underserved communities. But RMI also recommended that a single Solar Commons not exceed the 500kW size (Brehm & Lillis). Up to the 500kW scale, a Solar Commons project, they found, has a positive net present value. Meaning, at that size, the costs of the solar hardware remains significantly less than the amount of money that will flow out to a community beneficiary over the decades. Solar Commons up to 500kW are a great investment. A donor wanting to mitigate climate change and support community wealth building in low-income neighborhoods would feel confident in funding a Solar Commons array. A good corporate neighbor with a flat, big box store or factory roof could install a solar system and use the Solar Commons toolkit to pass their electric bill savings on to underserved rural or urban neighbors. City, county, state and federal entities who want to decarbonize their buildings can invest in up to 500kWs of solar, pay off the costs of the system from a few years of solar savings, and then pass on the savings from remaining years to a community trust. Public entities can thus support a more vibrant, grassroots democracy by sharing these common wealth trust funds with community groups and schools who will use the tools of solar commoning to thoughtfully deliberate, budget, vote and follow up on the use of their neighborhood dollars. Schools and neighborhood groups would learn basic guiding principles of commons—reciprocity, social equity, mutual aid and benefit—and celebrate yearly events in which common wealth trust funds were dispersed to local community projects.

Solar Commons applied research has produced both practical and theoretical results. The discovery that Solar Commons will not work beyond the 500kW scale provides another kind of insight about solar infrastructure in a just energy transition. When the Rocky Mountain Institute analyses noted that after 500kW, a Solar Commons array would begin accumulating administrative costs that would take away from the community trust, it was calling attention to a culturally nonintuitive relation of size and value. A general principle of industrial production would associate larger scale with reduced cost of a product. But with solar energy, this is apparently not so. Why then, do we see hundreds of megawatts of solar farms in the Midwest suddenly covering fields where corn and soy once grew? These gigantic solar energy factories act much like the coal plants that preceded them, massive power generators extracting wealth from rural water, land, and communities to benefit distant urban centers and even more distant investor-owners. They are the result of solar equity firms and other green neoliberal players who financialize solar energy for market gain.

How much financial value is there in solar photovoltaics? It’s not easy to show. In California, an industrial scale solar farm located far off in the desert outside of LA can generate solar electricity at $.02/kWh. Rooftop solar located close to point-of-use generates electricity at $.10/kWh. Solar farms appear to produce cheaper electricity than rooftop solar. But if you calculate the transmission and substation equipment costs from wheeling that electricity from deserts to cities, the cost is around $.40/kWh (Cinnamon). Who gets financial benefits from distant solar farms? Monopoly, investor-owned utilities like Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) in California get a twelve percent guaranteed return on investment from the transmission lines they build and own. After passing costs on to their customers, they have one of the most secure investments possible. In California, PG&E has helped eliminate the net-metering rules that had made rooftop solar a net-positive value to residential homeowners and businesses for the past decade. In places where rooftop solar is subject to more consumer-friendly regulation, the cost of solar is strikingly different. In Germany, rooftop solar is generated at about half the cost as in the US. Why this difference? Because Germany created rules that benefit local solar installations and local solar businesses and thus keep the cost of solar more predictable and stable. In the US, on the other hand, solar equity firms dominate solar pv markets. They bundle and sell customers’ rooftop solar leases on security markets. Solar analysts are beginning to see similarities between today’s distorted solar markets and the distorted housing markets that lead to the Great Recession of 2008. Wall Street appears to be putting the emergent US solar industry on the verge of collapse (Semuels). But not before solar equity firms capture the vast credits and incentives that the recent federal infrastructure bill (the Inflation Reduction Act) has made available to solar owners, a tsunami of public funding flowing upward to wealthy corporate owners and away from households and local businesses.

Anthropologists of modernity have much to say about the logics and outcomes of scaling production and growing administrative systems. Anna Tsing observed that “if the world is still diverse and dynamic, it is because scalability never fulfills its own promises.” Within its limit of 500kW, a Solar Commons can be sited in diverse urban and rural places. It can generate a multitude of diverse community economy projects through grassroots participatory budgeting. The late economic anthropologist David Graeber noted that within the vast expansion of modern administrative management, those who experience bullshit in the system are generally left without cultural scripts to articulate their experience. The same can be said for those who seek real community benefits from today’s solar energy systems. Solar PV appears to be a twenty-first century technology trapped in a twentieth century property system. Centralized, investor-owned, monopoly utilities and solar equity firms are killing the distributed, community-owned potential of solar technology. And this is why the alliance among anthropologists, engineers, artists, and communities in prototyping Solar Commons projects is so essential. While solar market distortions keep the flow of solar value inscrutable, invisible, and directed towards Wall Street, Solar Commons digital dashboard tools will make those value flows visible, measurable, and transparently peer governable. Solar Commons community trust legal agreements will direct those flows to local common wealth trusts. And public art—through games, murals, and related commoning activities—will create cultural scripts so that kids and adults can talk about the values of solar and use them to serve the needs of their community. Solar Commons prototypes will be learning-sites for solar commoning which will always look like the community it is serving.

References

Brehm, K., Lillis, G. Solar Commons Financial Analysis Results: Solar Commons Project Analysis Phase 1 of 2 Rocky Mountain Institute, 2018. Accessed at https://solarcommonsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RMI_SolarComFinancialReportPhase1_.pdf

Brehm, K., Lillis, G. Solar Commons Scalability and Constraints Analysis: Solar Commons Project Analysis Phase 2 of 2 Rocky Mountain Institute, 2018. Accessed at https://solarcommonsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RMI_SolarComScalabilityReportPhase2_.pdf

Cinnamon, Barry. “Blame California Politicians for Electric Rate Increases.” The Energy Show. January 10, 2024.Accessed at https://cinnamon.energy/blame-california-politicians-for-electric-rate-increases/

Milun, K., McMahon, E., Kaufmann, D., & Espinosa, K. (2021). “The Role of Public Art in Solar Commons Institution-Building: Community Voices from an Essential Partnership among Artists, Community Solar Researchers, and Activists.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 8(2), 7-7. Accessed at https://pubs.lib.umn.edu/index.php/ijps/article/view/4492/2999

Milun, K., Walsh, T., & Pitner, M. (2022). “Bringing New Light to One of the Oldest Forms of Property Ownership: An Innovative Solution for Benefitting Underserved Communities Using the Solar Commons Community Trust Model.” Vt. L. Rev., 47, 384. Accessed at https://lawreview.vermontlaw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Vol.-47-No.-3-05_Milun_Final.pdf

Semuels, Alana. “The Rooftop Solar Industry Could Be on the Verge of Collapse.” Time. January 25, 2024. Accessed at https://www.yahoo.com/news/rooftop-solar-industry-could-verge-145455396.html

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. “On nonscalability: The living world is not amenable to precision-nested scales.” Common knowledge 18, no. 3 (2012): 505-524.

Cart

Search