An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

SfAA Oral History Project

Business Anthropology in Advertising and Brand Development: An interview with Timothy Malefyt for the SfAA Oral History Project

Timothy Malefyt ls Clinical Professor in the Gabelli School of Business of Fordham University. He worked at advertising firms including BBDO Worldwide and D’Arcy, Masius, Benton, and Bowles. In the interview, which was done by Robert J. Morais, Malefyt discusses cases where he was able to use his insights as an anthropologist to contribute to marketing efforts for various brands including Cadillac Cars, Home Box Office, Crayola Crayons and AT&T. He received his graduate training in anthropology at Brown University and earlier had a career as a dancer at the acclaimed Joffrey Ballet. The text was edited by John van Willigen.

Timothy Malefyt ls Clinical Professor in the Gabelli School of Business of Fordham University. He worked at advertising firms including BBDO Worldwide and D’Arcy, Masius, Benton, and Bowles. In the interview, which was done by Robert J. Morais, Malefyt discusses cases where he was able to use his insights as an anthropologist to contribute to marketing efforts for various brands including Cadillac Cars, Home Box Office, Crayola Crayons and AT&T. He received his graduate training in anthropology at Brown University and earlier had a career as a dancer at the acclaimed Joffrey Ballet. The text was edited by John van Willigen.

Morais: I'm here with Timothy de Waal Malefyt in New York City, and it's August 21, 2017. And we're going to talk about your life and professional history with regard to business anthropology. Where and under what family circumstances you raised?

Malefyt: All right. Well, this is, of course, relating to how I got into anthropology and business anthropology. So, I grew up in Michigan, Ann Arbor, a real college town, a great place to grow up. My parents, both academically inclined, my father is a Dutch Reformed minister, and got his PhD at Harvard in the Department of Religion and was at the University Reformed Church in Ann Arbor. My mother was a psychotherapist, she went to the University of Michigan, and got her degree. She was a brilliant woman, had a lot of clients, mostly professional clients, the people she worked with at the University in Ann Arbor. That was my setting growing up. I was always interested in psychology. As a kid, I would go along with her to many psychological meetings. I attended as a kid, I was aware of adults releasing feelings and being very emotional, and really analyzing what they were thinking and feeling about some of their issues in life. So, I started this problem approach, looking at life and how you could analyze it and you try to understand it from emotional points of view and metaphors that people had that they held on to while so this influenced me. I didn't go to college right away at 18, 19. I grew up in Ann Arbor and didn't want to go to the University of Michigan. But it was really gymnastics that kind of got me going. Very athletic in that sense. When I was 19, I went to Hope College in Holland, Michigan, and started to dance there. I was a gymnast and started to teach dance. And the choreographers, there were two. There was a show going on [at Hope College], Mack and Mabel and they said, “Well, you're a gymnast, you have a little dance background, would you join us?” So that started me in my interest in ballet, and at 20 years old, I left Michigan, and I went to New York to dance with the Joffrey Ballet. I was accepted into Ballet School, on a whim. I wasn't a great dancer, but I was really strong upper body, and I could partner with anyone, I could take the biggest women and lift them over my head. So, I could make them look good. That was dance. I danced there for a number of years. And I was at Lincoln Center performing when I saw Fordham University right next door. I thought I would visit there, and I just stopped there and found out that they had life experience credit. So, I thought well, fabulous. I can write about my dancing life career. I had a year or two of college before and I went to Fordham and that really got me into, I was in psychology, my background from my mom. Again, mother's a psychologist, father's a minister, anthropology is like the only thing I could come out of that. But I took psychology, I was a psychology major undergrad at Fordham University. And it was my last year at Fordham Undergrad that I took an anthro course. And I was reading Victor Turner and the Milk Tree [The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual, 1967. Cornell University Press] and cultures, the symbols, metaphor. It was really reading about the Ndembuo that I thought was so brilliant, how he took this idea of the milk tree [which] could have multiple symbols and mean certain things at certain times for some people and certain things at certain times for other people. But there was always this symbolic and a tangible element to rituals that he talked about and rituals that help people go through rites of passage and enter into society. I read that and I thought that was wonderful. And our professor at Fordham also I read about the peyote hunt. [Barbara G. Myerhoff, Peyote Hunt: The Sacred Journey of the Huichol Indians,1974, Cornell University Press].

Morais: Weston Lebarre wrote about the peyote cult.

Malefyt: No, it was peyote hunt. That was two influential readings, but the idea of, especially Turner, in the liminality, and that liminality could apply to college time. And that's why college campuses literally are built on these sequestered zones where you're betwixt in between and anything can happen and people develop their own sets of rules and everything. I thought that was a great idea of applying anthropological theory to modern day contemporary life. I love Victor Turner. So, in my senior year at Fordham undergrad, I applied to Brown. I went to Brown because I was interested in performance studies. I wanted to take my dance background and do something with it in scholarly application. So, this was when I applied to several schools, University of Chicago, and was accepted there. Brown, but it was meeting Bill Beeman [William O. Beeman]. Here's the influential name I'll throw out. Bill Beeman was still, he still is an opera singer. And I met with him, and I thought, this is great. He and I clicked right away. He loved performance studies and culture. He said yes, he's starting something with performance in culture at Brown. And that was it. He also worked with a big name in music, ethnomusicology with Jeff Todd Titon, you've heard of the name. We did a lot of folklore and music. I was all excited about going to Brown. At this time too, I met my wife who is from Spain. She had come from Spain to New York, and also heard about Fordham and was getting her master's in Communication. So, we met taking the GRE exam, in the basement of Fordham. And so, we started going out, and I accepted my entrance to Brown, and just did a little bit of commuting over the weekends. So interesting, at Brown, and this is how she was always, maybe because she's Catalan. She's a real pragmatist. They call them, the pragmatists of the Spaniards, Catalans. She said, “What are you going to do with a degree in anthropology.” We started going out, she was already kind of questioning that. Now, I started at Brown, I was taking, there was nobody at Brown, who was into business anthropology, this didn't exist. This is 1989, I enrolled at Brown. I started there. And there was a legendary guy who had taught at Brown, he had taught at Brown, Princeton, and MIT. And his name was Steve Barnett. So, I want to mention here, of some of the very influential people who [I contacted]. I think that's one thing I'll say later on, meet as many people as you can, you never know, with these contexts, what they'll do and how they'll turn out. And this was one, Steve Barnett. So, in 1989, this is before the Internet, and I did a phone search, whatever. And I found out that he was in New York City, Steve Barnett was alive and well. He was not teaching at the schools anymore, but he had a practice in New York. So, I called him on the phone, and this is the fall of 1989. student at Brown University, I said, “I've heard about you here.” And he was friends with Lina Fruzzetti, another anthropologist, who was the chair of the department at Brown, they were really good friends, they wrote a book together. For Steve Barnett, his daughter was going to Brown and was a good friend of Lina's daughter as well. So, they were close friends together. I played off these contexts. Get to know when you want to meet somebody, get to know their background, get to know who they are, what they've done, maybe contexts they have. So, I shared some of this information. And Steve Barnett said, “Oh, by all means, come to New York, visit me. I'd love to chat with you. I want to hear about what's going on at Brown and all that. Please come down.” And so '89 I came down to New York, I was going back and forth, traveling there anyhow. But I went down to New York City. Steve Barnett had started a practice in New York called Holen North America, H-O-L-E- N. And I remember this because that's a Swedish term for Hill, a little summit. And this was a practice that was supported by a Swedish organization. Holen North America. This was also where Rita Denny [worked], I met her early on, she was in Chicago, she lived there, and has always been there, but she had a connection. She was like their exterior office with Holen. And the first person I interviewed with was Maryann McCabe. And we've since had a long contact as well as writing articles together and so forth. But Maryann interviewed me, and I met Steve Burnett. He was in and out. Very impressive guy. He had a column in AdAge. And he introduced me to Maryann and all the other anthropologists. John Lowe, Maryann McCabe, Vic Russell. So I met with Maryann, Rita, and Steve, and they said, “What do you want here?” It was a cool loft setting in an old pre-industrial building in downtown Manhattan near Wall Street. And I said, “I'd love to do some kind of work for you.” Well, they had no idea what to do. And I suggested an internship. So, in a way, that's something else, it is trying to figure out how you can be helpful. I said, “you don't even have to pay me. I'd like to do this.” It just sounded interesting. I had read some of Steve Barnett's AdAge columns, and it was really cool how he took, he had like a culture scope. He'd look at people walking in the street or clothes that they wear or food that they eat, read and make cultural insights into that. So, I said, “I would like to do a summer internship for you. So, they said, “Well, okay, we will get back with you.” They came back. Steve Barnett had left and went to Nissan, was a corporate executive at Nissan, but Maryann and Rita then hired me for a summer internship. In 1990 I started one of my first projects was listening to people in a hotel. And they gave me these tape recorders with recorded interviews on them. And they said, make sense of what people are doing with the hotel. Are there any issues that they have? And I didn't know what to look for. I thought, “what am I listening for?’ We're listening to these people talk about their experience going into a hotel. And I remember a man talking about how when he walked into a room, the first thing he noticed was the scent, the smell, how he felt at home or not, according to how fresh the room was or not. So, I mentioned that, and I said, he threw off his clothes, took his clothes off and sat on the bed naked. And when the maid service came around and knocked on the door and just opened the door. The man was caught off guard. So this led to some insights about how the hotel becomes your space, it becomes a home space that some people define for themselves right away. And so the immediate feeling you have when you enter a room is to connect with the room or not, or then there's some dissonance. This was a helpful insight. So, this was my first project I worked on, I remember that. This was with again, Holen North America. And that was my first project there.

Morais: So, what was in your reading when you were in graduate school, you weren't reading about business anthropology.

Malefyt: No. We’re reading traditional anthropology. Brown then didn't have the four-field approach. We were lacking physical anthropologists, but they were strong in sociolinguistics. That was really a strong influence with me, reading about how language not only is symbolically meaningful, but language can do things. We read how languages helped form communities, people can identify with metaphors, how different groups distinguish themselves by the language that they're using. And I also learned about the terms emic and etic, how Insider's use of language is different from an outsider's use of language. So, some of the theory that I had in socio-linguistics was very helpful in my advertising career, but we read more traditional works, you know, Malinowski, Coral Gardens and their Magic. We read some of the Victor Turner, Clifford Geertz, of course, it was a very, very traditionalist anthropological approach. I was questioning pursuing a degree in anthropology until I met Steve Barnett. And that kind of gave me a motivation to, I had a sense, this is what I want to do. So, through my years at Brown, I would go back to work weekends with Holen, of course, I was also going out with my wife in New York. But I also would work weekends at Holen North America.

Morais: So, this is interesting. One part of your brain was in business anthropology. And the other one was in a traditional anthropology program, and you went to Spain for your fieldwork and studied performance.

Malefyt: I worked at Holen North America all through my graduate school. On weekends, I'd come home. Now, I was still working at Brown with Bill Beeman, and he was a performance anthropologist, and I, taking my dance background, my dissertation was on flamenco as a tourist form of culture in Spain. I received a Fulbright fellowship to go there, and an NSF grant fund to go there as well. I'd already known my wife and we went to Spain on this grant, and I studied performance in culture. So, I was taking courses, I was doing work with Holen, I had liked that kind of approach. But I was a performance anthropologist, when I came back in ‘95 and then graduated ‘97 There was no work to be had in academia as a performance anthropologist, and Spain was my culture area, which was not a new or popular culture area; it had been done already by the likes of Pitt-Rivers and all the community studies about Spain. So, I went back to my Holen background, and in 97, I applied for a job at Wayne State. And I met Marietta Baba there.

Morais: In business anthropology?

Malefyt: Yes. So, I was going to try that route. And I didn't get the job there. But in 97, because of my Holen background, so no jobs in academic anthropology, or performance studies or anything. But in 97, here's serendipity. And this is something else I'll talk about at the end, always keep open to serendipity. If you put yourself out there, things happen! In a sense, the sense of confusion and ignorance can be something powerful and directive. So, I had sent out, it must have been, 50 different CV's for positions, and couldn't get a job in academia. But then I sent my resume to a headhunter in New York. The executive recruiter’s daughter had danced at the Joffrey school and also went to Brown. So, he picked up mine, and called me, saying, “This is a terrible resume, way you've written as it is, this is really terrible.” He said, “You've got to, first of all, you know, talk about what you've done. Talk about some problem or challenge you confronted in business and how you found a solution.” So, he helped me rephrase a lot of what I did at Holen into more business terms, again, taking an issue that was given and then discussing briefly how I resolved it or how our firm did and my part in that. I put that into my resume. And so, he sent it out, and said, they're looking for an account planner at AF&G. Account planning was something new that was developing an advertising in 1997. And he said, Avrett, Free, & Ginsberg is a small agency, Frank Ginsberg and Jack Avrett run this. It's in New York, they have some really great accounts. They have the Ralston Purina account, they have the Enterprise Car Rental account, and they have the Crayola crayon account. So, he sent my resume over. And Stuart Grau called me up and said, "Would you like to come out and interview." They flew me out.

Morais: Did you know what account planning was?

Malefyt: No, I had no idea. The guy who hired me, Stuart, was director of account planning. And he was looking for innovative ways to help do client research. So, he saw that I was an anthropologist, I had some corporate work. And so, he eventually hired me, he flew me out. And, you know, they started me at 55,000 a year, which was just phenomenal for me in 1997. I was so happy to make that kind of money. It was way more than I had expected. They helped pay for some moving expenses, not all of it, but so my wife and I, we married before then went out to New York and I started in 1997 at Avrett, Free, & Ginsburg. So, my first account was Crayola. And you know, in advertising you learn about the client's business, you learn what they're into. And Binney and Smith is the corporation for Crayola. And we went out and talked with them. And they had focused on moms, moms were the gatekeepers, they thought for kids. I have to say I didn't know much about account planning and I kind of got my feet wet. I look back in retrospect and I would have come up with more. I think I should have used anthropology more to help guide some of my insights into the whole childhood thing. But some of my background in psychology was helpful in developmental stages and what kids are into at different stages. I was at Avrett, Free & Ginsburg from 97 to 2000. And then I went to Detroit and worked at D’Arcy. D’Arcy, Masius, Benton, and Bowles, was helping Cadillac develop a new campaign and they wanted fresh insights. My wife was being picked up by Ford Motor Company, which wanted her back in Detroit so the timing worked for both of us. And I was looking for a change. So, I interviewed for D’Arcy, Masius, Benton and Bowles in Troy, Michigan.

Morais: In account planning?

Malefyt: In account planning, yes.

Morais: Can you describe that for our audience?

Malefyt: I am not an anthropologist yet in a business context. I had to be an account planner, first

Morais: But what explains what account planning is?

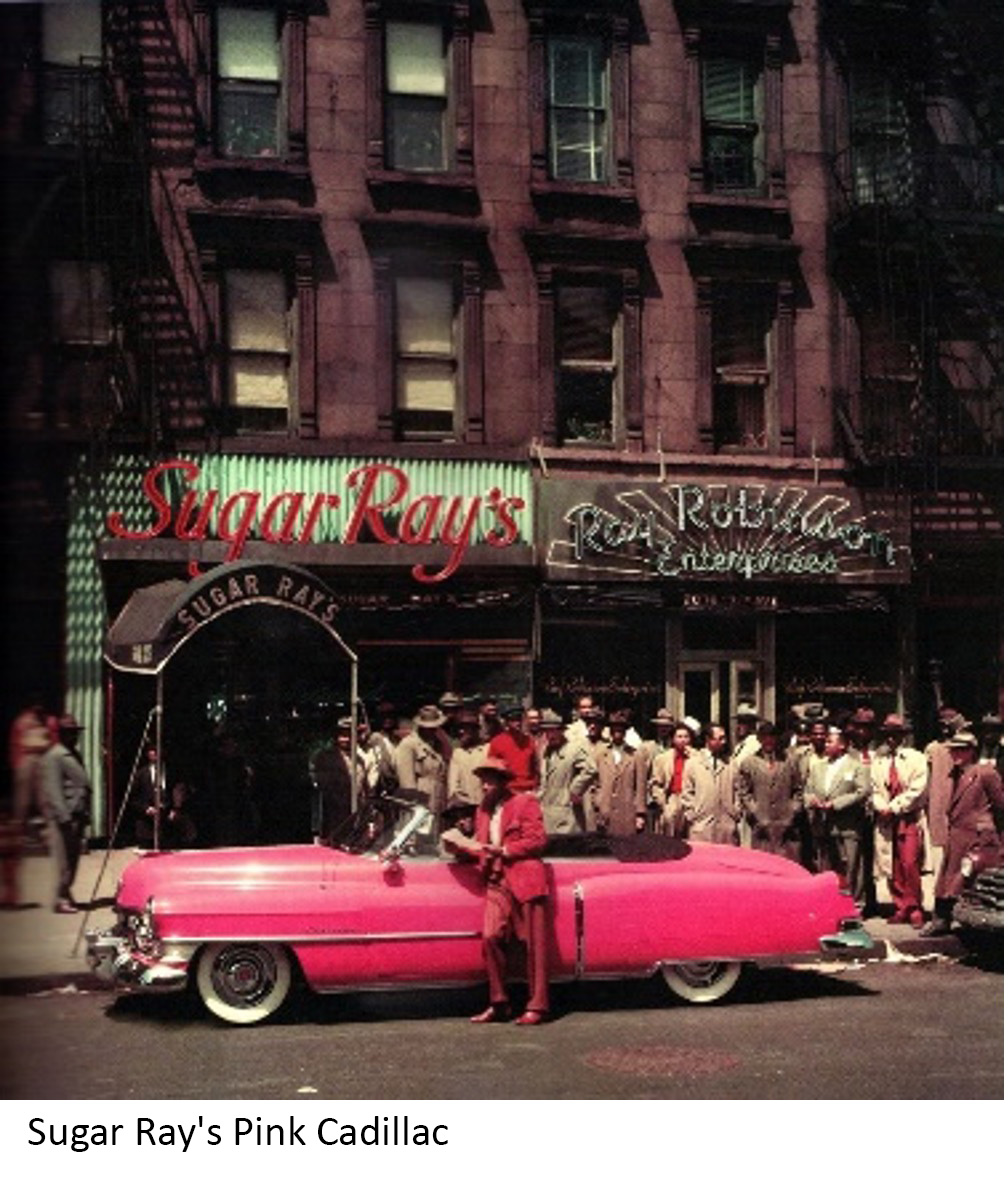

Malefyt: Account planning is a new, fairly new discipline in advertising. It actually started in England. But actually, it was a novel approach. Before, you had a research department that farmed out a lot of its research on consumers, and would bring ideas in that were general – etic – which were presented as consumer trends. And they would be adapted into advertising strategies. Account planning changed all this. The whole point is that the advertising cycle is a bigger cycle and has many different types of media and ways to connect with consumers, and you really need the voice of the consumer inside the agency at all these different media points. You need an advocate for the consumer for the person inside the agency. All the different media points an ad campaign uses are really different social contexts, and anthropologists are specialists in interpreting meaning in context. So, you can see anthropologists are really good for account planning because they know social contexts and how messages can be interpreted by consumers or fail to. And that's really a very good outlet for a lot of anthropologists. How do you understand the consumer of a brand or service and develop all the touch  points of where he or she makes contact with the brand, how they use it, the experience they have with the brand. This is a discipline that was developing in advertising. So, I was brought in in ‘97, as an account planner, and then at D’Arcy in Detroit. Account planning was really big. They had me work on the Cadillac account. So, I was excited about that. My wife was at Ford, I was going to be at work on Cadillac. This was a time when Cadillac was a dead brand. It was a brand that was known for grandmothers, and this was a time Cadillac cars were big and clunky. So I went out on some research. We did this research on Cadillac. And what we found is, you know, to ask a different set of questions, cultural questions (See Patricia L. Sunderland and Rita M. Denny, Doing Anthropology in Consumer Research, Routledge 2007). If you ask the obvious business questions, such as, what do people want in a luxury car? They will tell you certainly not a Cadillac. They'll tell you they want high quality and Lexus or Mercedes has that, or they want high performance car and BMW has that. But Cadillac was a big lumbering car and was really not what people would ask for or what they wanted in a luxury car. But when asking people what success in life meant to them, we started hearing people talk about the American dream and making it! This is where anthropological research and interviewing is really critical. We started hearing people talk about the American dream, and how they maybe came from an underprivileged background, or that their family didn't have a lot of money and were new arrivals to America. But when they started to earn money themselves, when they started making these notches in their career, they were succeeding towards the American Dream. The whole idea of success was critical to them, and American success represented something very special for them. And then we said, “well, what happens when you succeed in life? What do you do when you succeed?” Well, from their humble beginnings, they said, “Well, when you succeed, you want to show off big, you want to celebrate. You want to show people that you've made it, that you've earned it.” They have arrived! So, we started rephrasing our questions about Cadillac in terms of the American dream, and Cadillac was a car about reaching dreams. It was all about a car that people arrived in, especially famous people, like Presidents, Movie Stars,. So, Sugar Ray Robinson, the famous boxer, drove up to his restaurant in a pink Cadillac and arrived to all the crowds gathered around.

points of where he or she makes contact with the brand, how they use it, the experience they have with the brand. This is a discipline that was developing in advertising. So, I was brought in in ‘97, as an account planner, and then at D’Arcy in Detroit. Account planning was really big. They had me work on the Cadillac account. So, I was excited about that. My wife was at Ford, I was going to be at work on Cadillac. This was a time when Cadillac was a dead brand. It was a brand that was known for grandmothers, and this was a time Cadillac cars were big and clunky. So I went out on some research. We did this research on Cadillac. And what we found is, you know, to ask a different set of questions, cultural questions (See Patricia L. Sunderland and Rita M. Denny, Doing Anthropology in Consumer Research, Routledge 2007). If you ask the obvious business questions, such as, what do people want in a luxury car? They will tell you certainly not a Cadillac. They'll tell you they want high quality and Lexus or Mercedes has that, or they want high performance car and BMW has that. But Cadillac was a big lumbering car and was really not what people would ask for or what they wanted in a luxury car. But when asking people what success in life meant to them, we started hearing people talk about the American dream and making it! This is where anthropological research and interviewing is really critical. We started hearing people talk about the American dream, and how they maybe came from an underprivileged background, or that their family didn't have a lot of money and were new arrivals to America. But when they started to earn money themselves, when they started making these notches in their career, they were succeeding towards the American Dream. The whole idea of success was critical to them, and American success represented something very special for them. And then we said, “well, what happens when you succeed in life? What do you do when you succeed?” Well, from their humble beginnings, they said, “Well, when you succeed, you want to show off big, you want to celebrate. You want to show people that you've made it, that you've earned it.” They have arrived! So, we started rephrasing our questions about Cadillac in terms of the American dream, and Cadillac was a car about reaching dreams. It was all about a car that people arrived in, especially famous people, like Presidents, Movie Stars,. So, Sugar Ray Robinson, the famous boxer, drove up to his restaurant in a pink Cadillac and arrived to all the crowds gathered around.

We rephrased and from this ethnographic research that we did with Cadillac, that it was not so much about Cadillac, the brand as a luxury car, but a car about arrival, a car that broke through and showed your American success story to others. We developed the whole ad campaign around American success, about making it, about breaking through and showing your success. And actually, our tagline came from the research breakthrough. And we hired Led Zeppelin to the account team. $8 million, they paid them to use a bit of their song they hired them to use the song "It's been a long time since we rock and roll." And this was a very successful relaunch of Cadillac in the 2001 Super Bowl. It was in the 6th spot. GM hadn't spent a lot of money on ad spends before. This was a big ad spend. And it moved the brand from number six in the luxury car position way behind Lexus, Mercedes, BMW, Audi, the other cars, and it moved up to number three in three years. So, this was an insight for that brand came from thinking and talking to consumers and not redirecting questions about what a luxury car would be about, but really talking about what the success of making it in life meant and how to celebrate that. So, this is something we use for advertising.

We rephrased and from this ethnographic research that we did with Cadillac, that it was not so much about Cadillac, the brand as a luxury car, but a car about arrival, a car that broke through and showed your American success story to others. We developed the whole ad campaign around American success, about making it, about breaking through and showing your success. And actually, our tagline came from the research breakthrough. And we hired Led Zeppelin to the account team. $8 million, they paid them to use a bit of their song they hired them to use the song "It's been a long time since we rock and roll." And this was a very successful relaunch of Cadillac in the 2001 Super Bowl. It was in the 6th spot. GM hadn't spent a lot of money on ad spends before. This was a big ad spend. And it moved the brand from number six in the luxury car position way behind Lexus, Mercedes, BMW, Audi, the other cars, and it moved up to number three in three years. So, this was an insight for that brand came from thinking and talking to consumers and not redirecting questions about what a luxury car would be about, but really talking about what the success of making it in life meant and how to celebrate that. So, this is something we use for advertising.

Morais: That's a great story, because it demonstrates how sometimes you don't know where you're going to end up. You know, when you're following through with questions, it can lead you from one place to another. Unlike when you have a questionnaire or when you have a moderator’s guide, you control the situation. The one, I want to get a little bit to how you see business anthropology evolving. What do you think is going to happen? What is happening now in business anthropology, what's going to happen next in business anthropology?

Malefyt: So, this is anthropology. It is a whole new field when you and I started off in this. All of us have had these kinds of serendipitous stories of fate and things coming along and happening that way. You know, anthropology as a discipline, I think, is so valuable because I teach this in my courses. One thing that I teach about is getting this native point of view. And this is anthropology, I think I'm speaking maybe more from a marketing point of view, but we teach marketing to students, I teach marketing to students, you know, the knowing the value proposition, knowing that the positioning, knowing the competitive environment, knowing what are the attributes of the brand that you can communicate to the consumer. And these, this is kind of a formal way of looking at marketing point of view, anthropology adds this. What's the human problem, the human issue when you're looking at something, and it's turning a business problem into this human problem, and then how we can turn it back into a business solution, I think the anthropologist will continue to look at a traditional discipline like design, like management, like marketing, look at the language and the framework of the way business people and designers use that language and that information, and then develop this comparable or compatible emic point of view. And then that helps feed back into the business problems or the design problems, and the two make the insights stronger. Remember, one of the big things with anthropology, it's holistic and comparative. Anthropology in its foundation looks to compare one cultural set of behaviors to another cultural set of behaviors, this is exactly what you have in a business or design situation. And when you get another perspective, and then can feed that back in, again it makes it insightful. And that's where you can come up with solutions to problems.

Morais: So far, that's a great analysis, and then now I want to go back a little bit to your career trajectory, because you after D’Arcy, you joined BBDO. And you were a full-time anthropologist heading up a Cultural Discovery Group. And how does the work you just described define the value of business anthropology? Did your clients and your agency colleagues see the value the same way you do? Or do they look at it differently?

Malefyt: Thanks, that's a good lead in. And so from Avrett Free & Ginsburg to D’Arcy, I was an account planner. And that's really what my job was. I was an account planner. And then in 2003, this was from Lynne Seid, who was at BBDO. And Martin Straw, who was the Chief Marketing Officer at BBDO. They were redoing a whole department at BBDO. The whole agency was going through a change. And so, he said, I was looking for an anthropologist in my work at Cadillac with Pam Scott. She was a connection to Lynne Seid who was the new businessperson, the chief new business officer. And so, Pam said let me introduce you to Lynne Seid who connected me to Martin, and he was looking for an anthropologist. So, he said I was, I happened to be looking for an anthropologist and your name just came on my desk. So, they flew me out for an interview, and I got the job in January 2003. And this is the first time I wasn't an account planner, but an anthropologist, so they wanted to start and we started a whole group within BBDO, which was called Cultural Discoveries, as you mentioned, and it was unlike in advertising, typically, and you know what this is, like, Bob, you work on an account or two or three, you have certain  account relationships, and you develop relationships with the client, and you know, your creative team, you know, your production team, and you work within that. This job at BBDO allowed me to work across all brands, and BBDO had a big portfolio. So I worked on brands from New Balance to AT&T to HBO, and these were all these were all clients that were looking for deeper kinds of insights and, and to go from, Yeah, we were looking for deeper insights. So I was, in a sense, my first level of clients were the account planners at BBDO, and the account executives who were dealing with building relationships. So, I did work with these guys who were the account planners and, and the account executives. We had relationships with their clients, and they said, we have an anthropologist inside and we want to give you these insights. Now, one thing I want to talk about building on the idea of account planning, the good thing about having written about this in our book, Advertising and Anthropology (2012), is that the reason it's great having an anthropologist inside an agency is that you go out to do the research, you come back with the research, but you can follow through with your ideas through the whole advertising process. So, it’s not just giving them your research and handing off and saying you're done, you figure it out, you come back and forth. And you help them write the creative brief, which is really a critical document that guides the creatives, the creatives that come back to you with ideas about just this, this taps into what you saw with your consumers. Let me give you an example of that.

account relationships, and you develop relationships with the client, and you know, your creative team, you know, your production team, and you work within that. This job at BBDO allowed me to work across all brands, and BBDO had a big portfolio. So I worked on brands from New Balance to AT&T to HBO, and these were all these were all clients that were looking for deeper kinds of insights and, and to go from, Yeah, we were looking for deeper insights. So I was, in a sense, my first level of clients were the account planners at BBDO, and the account executives who were dealing with building relationships. So, I did work with these guys who were the account planners and, and the account executives. We had relationships with their clients, and they said, we have an anthropologist inside and we want to give you these insights. Now, one thing I want to talk about building on the idea of account planning, the good thing about having written about this in our book, Advertising and Anthropology (2012), is that the reason it's great having an anthropologist inside an agency is that you go out to do the research, you come back with the research, but you can follow through with your ideas through the whole advertising process. So, it’s not just giving them your research and handing off and saying you're done, you figure it out, you come back and forth. And you help them write the creative brief, which is really a critical document that guides the creatives, the creatives that come back to you with ideas about just this, this taps into what you saw with your consumers. Let me give you an example of that.

Morais: it sounds like you found that very rewarding,

Malefyt: It was really, really rewarding to work all the way through the advertising process. And you get to see the advertising is not one singular advertisement and then it's done. It's a whole sequence of activities, it starts with some creative work, it starts with the development process, you're looking for an exploratory idea, you're looking for a way to latch on to a consumer insight, then there's the whole strategy development, and then there's a whole creative development. There's all these different phases of advertising development that go into any single campaign. And then there's different media that you use for that. So, an example is New Balance. We did ethnographic interviews with people who were runners from moderate to extreme runners. And we found out that, you know, some people don't run just for exercise, they do it to feel good afterwards. There's a sense of tension when they go into running, they love having run, they love the feeling they get after they've run, but a lot of people hate to initiate it, hate to get into it. So, there's this kind of love-hate paradox. And you know, people talk about feeling so good after they ran. I just felt so clean, and my mind is fresh and ready to go for the day. But other people talk about how I dread running today. I don't look forward to it. So, it seemed like a lot of the way people talked about running was like a relationship with somebody. There was this love-hate ambivalent relationship with somebody you love them hate them at different times. And this actually came built into our whole strategy love-hate this is the New Balance and we talked about we played with the word balanced with this that people don't want to do it but in a committed relationship, you're going to keep at it, you're going to stick with it through the ups and the downs and that's really the relationship you have with yourself and running.

Morais: I'm smiling for anybody listening to this, it's a great insight.

Malefyt: One another, very rewarding. HBO is a brand we worked. Home Box Office and one of the insights we went out and talked with and you know, the client is kind of thinking okay, we know about our brand we know it's a very high artistic brand we know people like this and they love the brand but we went out and talked with people and we said “What's another way,” This is also where anthropology and psychology and other ways have come into this what are we to get into the way people what you listen for one of the insights I learned in anthropology the difference between what people say and what they don't say. You talked about earlier the significant making the strange familiar and making the familiar strange. Another thing is listening to what people say you're going to say is the unexpected sense of what people don't say. So how can we move beyond what people say about loving HBO? The client had a lot of information from survey work that people love the brand. People watch it all the time, they feel good about it, they are accustomed to it. So how can we push insights even further, and this is where as an anthropologist, you're always thinking of ways to get beyond that. Well, after just reading John Steel's book, Truth, Lies and Advertising. He used deprivation as a way to get people to talk about something that is so common and familiar for people that people aren’t used to talking about it. A way to get insights about something so familiar to them, is to take it away, deprive people of it, so, they don't have it. And with HBO, we decided to do this, I talked with the planners on this. We said, “let's talk to people, people who love HBO, and let's take it away from them for two weeks, and see what happens.” We paid them a lot of money, we found 12 recruits. It wasn't a big sample. We did this in the New York area. And this isn't the time when Sex in the City was really high. This is 2006 2007. The Sopranos was a really big series. And we said, “Okay, we're going to deprive you for two weeks, you can't talk about it. You can't watch it; you can't read about it. You can't go online and find out what happens. You can't have anything to do with them with HBO for two weeks.” We paid them 600 bucks for this, we're going to go interview them. So, incentive, first of all, out of the 12, we had two people drop out because they were so into the show. They couldn't not watch it. We recruited two others, we had 12 altogether. But we went out to interview them. And what we found out was the deprivation is that, yeah, of course people love watching HBO. It's an exciting show, and they talk about it. But the value of HBO came later on, not on Sunday when they're watching The Sopranos, or Sex in the City. But on Monday, when they would go into the office and talk about it with others. Talking about the show gave them a kind of social currency. So, we came up with this idea. HBO makes them storytellers. This is something you learn in advertising, combining advertising and anthropology together, we came up with a new target name called socialentees. These are social loquacious people who love the brand because it gives them something to talk about; it gives them social currency. And it makes them intellectually and culturally smart. So, this is a brand that empowers people by making them current on events, they can talk about and discuss things. And we only found out about this dynamic by taking HBO away from them. So, this insight led us into a whole campaign about HBO making people smarter via cultural currency. And David Lubars later used this to develop this Voyeur campaign projecting 8 films of 8 different people’s lives onto the outside of a building, where the wall of these people’s apartments was cut-away so you could peer inside and see their lives, as stories unfolding – the drama, crime, cheating, even murder, that other people wouldn’t normally be able to see. And it was all about promoting the power of storytelling. So HBO made people better storytellers. And so, insights from using ethnography and deprivation were very useful and satisfying. Nothing's more satisfying than to see TV commercials that you've had some part in creating.

Morais: Now, so you did this for BBDO for quite a few years. And then you moved to Florida. As a full-time faculty, why did you decide to do that?

Malefyt: Okay, well, 15 years in advertising, loved it.

Morais: You were teaching part time at the New School?

Malefyt: Yes, yes. I would give advice to business anthropologists to always have some academic connection, trying to make an academic connection. You've done that very successfully. You're an adjunct at Columbia, you teach in the business school. It's great to keep that connection going. I was asked to teach at Parsons School of Design, which is part of the New School. I just published the book, Advertising Cultures with Brian Moeran. [Timothy de Waal Malefyt and Brian Moeran, Advertising Cultures.] I met Brian at a 2000 conference. And we just developed that contact all the way through and came up with Advertising Cultures. But it was then in 2004, after I came to New York, and I started to teach it, or as I was at BBDO, Meg Armstrong, who's the Chair of the design and management at Parsons said, you know, we’ve read my book, and would I be interested in teaching at Parsons? So, I taught a science of shopping class at Parsons, advertising strategy class, and branding class at Parsons. Three different classes. I was at Parsons for most of my time at BBDO. In 2012, I just felt ethnography was getting a little tired. I'd been at BBDO, nine going on 10 years. And it was a contact at Fordham, Paul Riley, who was a senior EVP at BBDO, who was on the board at Fordham said, you know, you'd be interested in doing a talk over there. So, this was the time we you and I had met, and we were thinking of business anthropology, and I was eager to try to start something maybe some program at Fordham In business anthropology, so, in 2012, I left BBDO. And I went to start in the fall at Fordham University, at their business school in their marketing department. And I think this is really a future for a lot of anthropologists. As of now, I think there's a welcoming, you get the sense, I hear from Chris Miller and from Ken Erickson, these are other anthropologists who are teaching in business school settings. There's a welcoming of this kind of qualitative insight, the way we can understand culture, the way we can bring this in, I think there's a great value for them. I think the future is maybe. If enough business or maybe if enough anthropologists are hired and business schools, anthropology departments will start to embrace it as well. So, I've been at Fordham now for five years, teaching in marketing. And slowly we're starting some, I'm the director of the Consumer Insights Program. And we're starting some courses in consumer insights in business anthropology. So, we're trying to develop a business anthropology program, undergraduate at Fordham.

Morais: So, what advice would you give for somebody graduating with a bachelor's degree in anthropology or a master's degree? Who's interested in doing what you do? Or did certainly in advertising? What would you say to them now?

Malefyt: I'd say, good advice is if you've been in anthropology, and you're getting an anthropology degree, finish that, as it’s great to have. And then I think having some marketing or business courses are going to be critical, you know, as anthropology is comparative, you need to know how marketers, how managers, business managers, how designers think, there's a way of thinking, way of using language, a way of structuring data, of understanding, in a sense, the other and I would say, Take marketing courses, management courses, take design courses, so you cannot just develop the language, but a way of thinking, understanding the relationships that they have. Because, as we've talked about advertising, it's about how you service the industry, how you service your client, how do you understand the client's needs and anticipate what they're going to know about? And recommend strategies for them? Likewise, in business schools, I mean, we're taking business classes you learn about a problem-solution approach, I think it's a divergent kind of thinking where anthropology, at times can be very convergent. And leave you thinking that things are more complex, and you just leave it at that. This is a critical approach, deconstructing a situation, examining complexities, but then what does that leave you with? In business thinking there's kind of looking forward types of solutions. And I think that is helpful for anthropologists to supplement their education with these kinds of courses. And one other thing I want to mention, is words of wisdom that you can offer your students and colleagues considering applied work is often, I love this article to be open to confusion, because serendipity comes from confusion. There's a great article by David Gray, the value of ignorance, and he talks about, there's the tyranny of knowledge. This applies a lot in business, when businesses know a lot about something they tend to find answers to what they're looking for even before they start off with something. So, the idea of confusion of openness, even ignorance can be something valuable to look at new ways, new insights and putting those things together you had never figured before. So that would be my advice for others. And I think there's a great future for business anthropologists, I'll conclude by the same that I think business anthropology, anthropologists are welcomed in business schools and marketing programs. And as you and I get this going at the AAA, I think there's going to be more openness in academia to business ways of thinking that profit is not what it's all about. But, one thing I've learned about in marketing, it's not about making the sale, it's about creating value for the customer. And what is that value relationship between a customer and the brand or the company? And value is something that anthropologists can talk about greatly? What is the value, how can we increase that value? So, with this I conclude that anthropologists are highly needed in the business setting, and I hope to see more of them.

Morais: Great, thank you.

Further Reading

Malefyt, Timothy de Waal and Robert J. Morais. Advertising and Anthropology: Ethnographic Practice and Cultural Perspectives. 2020. Routledge.

Malefyt, Timothy de Waal and Robert J. Morais, eds. Ethics in the Anthropology of Business: Explorations in Theory, Practice, and Pedagogy, 2017. Routledge.

Moeran, Brian and Timothy de Waal Malefyt. Advertising Cultures. 2003, Routledge.

Moeran, Brian and Timothy de Waal Malefyt. Anthropologists At Work in Advertising and Marketing. In Riall Nolan (Ed.), Handbook of Practicing Anthropology, New York and London: Wiley/Blackwell, pp. 247-257.

Cart

Search