An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Making a Career in Development Anthropology:

Making a Career in Development Anthropology: A SfAA Oral History Interview with Riall Nolan

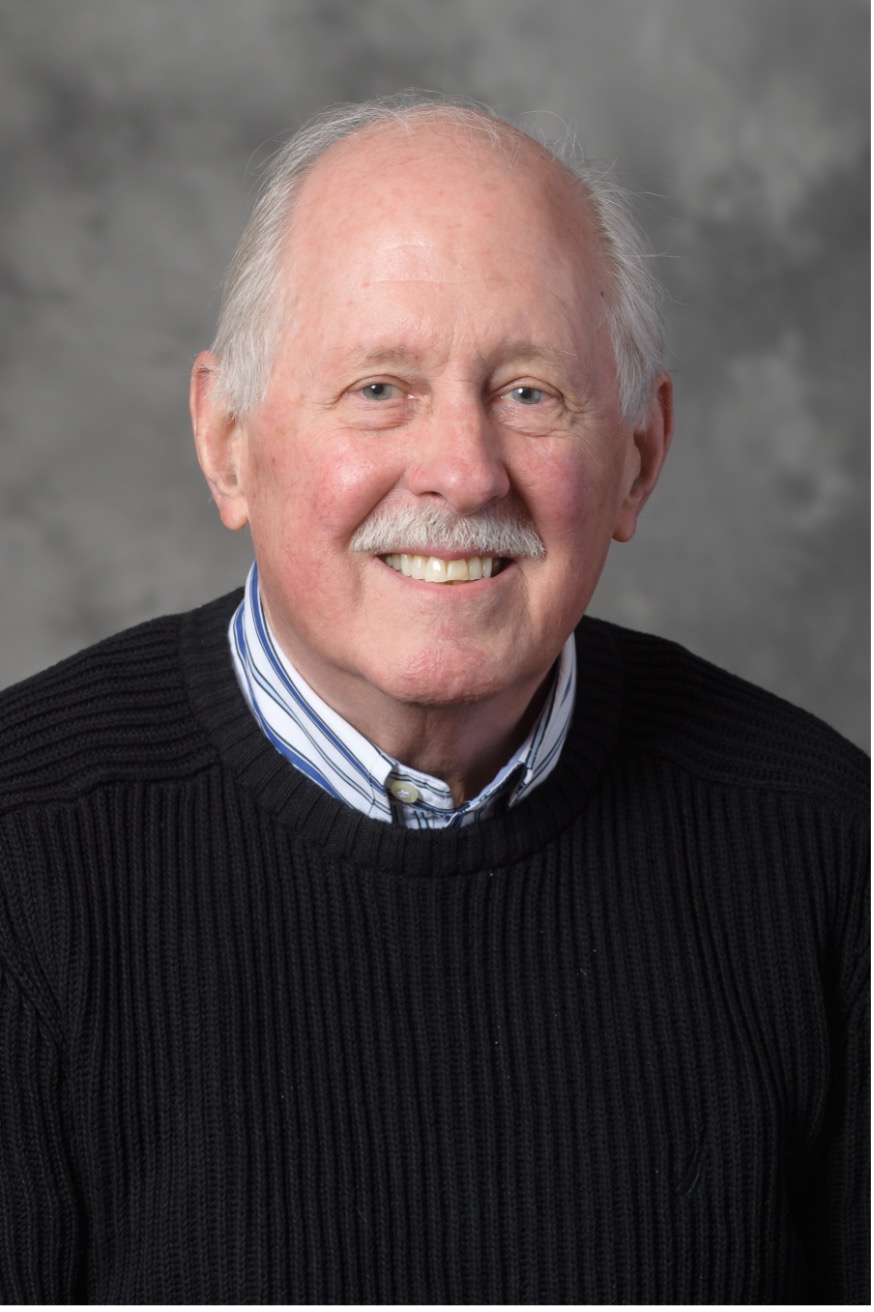

Riall Nolan has had a distinguished career in development anthropology in both agency and academic settings. He has done development work with various agencies including the World Bank and USAID in Senegal, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Somalia, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Indonesia, and Thailand. His career in development started with a three-year posting with the Peace Corps in Senegal. He recently retired from Purdue University as Associate Provost and Dean of International Programs. Nolan’s preparation was at Colgate University and the University of Sussex. He was recipient of the Society’s Sol Tax Distinguished Service Award this past year. The interviewer was Elizabeth K. Briody. The transcript was edited by John van Willigen.

Riall Nolan has had a distinguished career in development anthropology in both agency and academic settings. He has done development work with various agencies including the World Bank and USAID in Senegal, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Somalia, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Indonesia, and Thailand. His career in development started with a three-year posting with the Peace Corps in Senegal. He recently retired from Purdue University as Associate Provost and Dean of International Programs. Nolan’s preparation was at Colgate University and the University of Sussex. He was recipient of the Society’s Sol Tax Distinguished Service Award this past year. The interviewer was Elizabeth K. Briody. The transcript was edited by John van Willigen.

Briody: This is Elizabeth Briody, and I am here with Riall Nolan on March 22, 2017, and we're going to be doing an interview for the SfAA oral history project. So the first question that I'm going to ask Riall is to start back at the beginning, where and under what family circumstances were you raised?

Nolan: So, thanks for doing this. Very quickly. I grew up in upstate New York. My dad was a small-town doctor, my mother was a psychologist. On my dad's side, it was Irish working class. I wouldn't be surprised if my grandfather didn't work on the railroad with your dad. We started in the Hudson Valley outside of Saratoga, my dad moved us to Syracuse after a little while and then eventually we wound up in Geneseo, New York, south of Rochester. So it's all been upstate New York. I'm the oldest of four kids, I have two younger sisters and a younger brother. Nobody else is an anthropologist. I was always the kid who went further than other people into the woods when we would go running around. I know as an anthropologist we're all hardwired to go over the hill and see who's over there. That's the way we mix up the genes. But apparently, I have a little more of that than most people. Because I would terrify my mother. I would be gone all day, and she'd say, “Where have you been?” I'd say, “I've been hunting tigers,” this at age five or six. I apparently did this a lot. And it was also fueled by other people in my family, my uncle, for example, who I never knew because he died before I was born. But my uncle was a fairly well-known war correspondent for The New York Times, a guy named Eddie Neil. And Eddie had been in Ethiopia when Mussolini attacked Haile Selassie. And he had been in Palestine when the Palestinians were fighting the British. He was killed in the Spanish Civil War on the front, as he was reporting it. And just as a piece of historical information, there were five reporters in the car that got hit by the shell. Eddie and another guy died. One of the three surviving ones was Kim Philby, the Russian spy who was at the time a war correspondent for the London Times. Anyway, all this by way of saying that when I was playing around as a kid at my grandmother's house, I would come across my uncle's memorabilia. He had swords from Ethiopia, he had coins from the Palestinian mandate, the British Mandate in Palestine, he had this and he had that. He had books, Sir Richard Burton's adventures, polar explorers. I read these things; I was obsessed with them. I wanted to get out of town at some point. And of course, eventually I did. So that was my growing up.

Briody: And tell, talk to us about your education in your education generally, and then how you eventually got into anthropology.

Nolan: Right. I went to undergraduate at Colgate University, and I did that for a very simple reason. I got a full scholarship. I wasn't all that interested in getting into the most prestigious place I could, but Colgate was a very good school. I knew that, and when they offered me a full ride and I said, “Fine, I'm up for that.” This happened about September of my senior year when all my colleagues were fretting over “am I going to get into Yale or Duke or whatever.” I was done. So I went to Colgate. I majored in psychology because my mom was a psychologist. I didn't like it, but it took me about a year or two to figure that out. By that time, it was too late to major in anything else, but I had minored in sociology and anthropology. And I had an epiphany, which I have described in other writing that I've done, in the spring of my senior year, 1965. I was sitting in my advisor’s office, a guy named Arnie Sio. [Editor: Arnold Sio was a distinguished professor at Colgate.] And Arnie Sio turns out to be one of the best friends of Linda Whiteford's parents. They all know each other. I didn't find this out until a few years ago but Linda and I have this connection back. Anyway, Arnie's in his office smoking his pipe, and he says to me, what's your plan after graduation? And I said, I don't know. I'm not signed up for graduate school. I'm not signed up for any corporate interviews. I have no job. I don't know what I'm going to do. And then I said something to him that is very typical of young men of my generation at that time. I said, I suppose if I can't think of anything better to do, I'll join the army and get my military obligation out of the way. Even though there wasn't a draft at the time, that's the way people thought because we had all grown up with the Second World War. And he just looked at me. He said, “You don't read the papers very much, do you?” And I said, “Why?” He said, “Well, there's a war starting in Southeast Asia, in case you hadn't noticed.” He then said, “So if you want to be part of that, by all means, join the army. If you'd rather not do that, if you'd rather do something else, think of something else. And don't join the army.” And I said, “Well, what?” And he said, “You seem to be very interested in anthropology, you seem to be very interested in the parts of the course that were about Africa.” He said, “Why don't you just find some way to get overseas and, you know, figure it out when you're over there. Join the Peace Corps, for example.” So that's what I did. And it changed my life completely. Two months after graduation, I was in Peace Corps training. Three months after that I was in Senegal. I had to look Senegal up on the map. And then my world opened up. I spent three years in Senegal, the happiest time of my life, in many respects. I learned languages not taught at Colgate, I got to be fluent in French, I got to be very good in a couple of African languages. And that's where the whole thing got started. I was doing community development, rural development work. I wasn't particularly good at it. But the Peace Corps didn't require you to be particularly good at these things. You just had to kind of stick it out. So I did. But I learned a lot. And language was the key. The Africans around me were strangers to me until I could talk to them. And then everything just started. Then something else happened, which was about halfway through my Peace Corps service. I was out in this place where there weren't very many white people at all. There was me, there was a female Peace Corps volunteer, there was a French missionary father, and two or three nuns. That was it. And then all of a sudden, I noticed there were two or three other white people driving around the village in a jeep. And I was really curious, who are these folks? I introduced myself and it turned out they were a French-Belgian anthropology team from the Musée de L’Homme in Paris. And they were out on a mission, an ethnographic, whatever, field thing. And so I got very curious. My French was good enough to sort of be accepted, you know, the way it goes with those folks. And I started spending the evenings sitting around with them, talking, drinking wine and whatever. And they said to me, “Why don't you come on out with us, if you’ve got nothing else to do? We're going to go out and do a little field work tomorrow.” So I said, Sure. We got in their Jeep, and we went out to a very remote place. I was already living in a very remote place, but they went to a place that was even remoter, somewhere I couldn't get to even on my bicycle.

Nolan: Right. I went to undergraduate at Colgate University, and I did that for a very simple reason. I got a full scholarship. I wasn't all that interested in getting into the most prestigious place I could, but Colgate was a very good school. I knew that, and when they offered me a full ride and I said, “Fine, I'm up for that.” This happened about September of my senior year when all my colleagues were fretting over “am I going to get into Yale or Duke or whatever.” I was done. So I went to Colgate. I majored in psychology because my mom was a psychologist. I didn't like it, but it took me about a year or two to figure that out. By that time, it was too late to major in anything else, but I had minored in sociology and anthropology. And I had an epiphany, which I have described in other writing that I've done, in the spring of my senior year, 1965. I was sitting in my advisor’s office, a guy named Arnie Sio. [Editor: Arnold Sio was a distinguished professor at Colgate.] And Arnie Sio turns out to be one of the best friends of Linda Whiteford's parents. They all know each other. I didn't find this out until a few years ago but Linda and I have this connection back. Anyway, Arnie's in his office smoking his pipe, and he says to me, what's your plan after graduation? And I said, I don't know. I'm not signed up for graduate school. I'm not signed up for any corporate interviews. I have no job. I don't know what I'm going to do. And then I said something to him that is very typical of young men of my generation at that time. I said, I suppose if I can't think of anything better to do, I'll join the army and get my military obligation out of the way. Even though there wasn't a draft at the time, that's the way people thought because we had all grown up with the Second World War. And he just looked at me. He said, “You don't read the papers very much, do you?” And I said, “Why?” He said, “Well, there's a war starting in Southeast Asia, in case you hadn't noticed.” He then said, “So if you want to be part of that, by all means, join the army. If you'd rather not do that, if you'd rather do something else, think of something else. And don't join the army.” And I said, “Well, what?” And he said, “You seem to be very interested in anthropology, you seem to be very interested in the parts of the course that were about Africa.” He said, “Why don't you just find some way to get overseas and, you know, figure it out when you're over there. Join the Peace Corps, for example.” So that's what I did. And it changed my life completely. Two months after graduation, I was in Peace Corps training. Three months after that I was in Senegal. I had to look Senegal up on the map. And then my world opened up. I spent three years in Senegal, the happiest time of my life, in many respects. I learned languages not taught at Colgate, I got to be fluent in French, I got to be very good in a couple of African languages. And that's where the whole thing got started. I was doing community development, rural development work. I wasn't particularly good at it. But the Peace Corps didn't require you to be particularly good at these things. You just had to kind of stick it out. So I did. But I learned a lot. And language was the key. The Africans around me were strangers to me until I could talk to them. And then everything just started. Then something else happened, which was about halfway through my Peace Corps service. I was out in this place where there weren't very many white people at all. There was me, there was a female Peace Corps volunteer, there was a French missionary father, and two or three nuns. That was it. And then all of a sudden, I noticed there were two or three other white people driving around the village in a jeep. And I was really curious, who are these folks? I introduced myself and it turned out they were a French-Belgian anthropology team from the Musée de L’Homme in Paris. And they were out on a mission, an ethnographic, whatever, field thing. And so I got very curious. My French was good enough to sort of be accepted, you know, the way it goes with those folks. And I started spending the evenings sitting around with them, talking, drinking wine and whatever. And they said to me, “Why don't you come on out with us, if you’ve got nothing else to do? We're going to go out and do a little field work tomorrow.” So I said, Sure. We got in their Jeep, and we went out to a very remote place. I was already living in a very remote place, but they went to a place that was even remoter, somewhere I couldn't get to even on my bicycle.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: And there we spent the day. They spent all day talking to old men and women using an interpreter, which I thought was odd. I thought surely you ought to know this language, but they didn't. Talking through an interpreter and collecting stories from these people. On the way back, I said, “So this was all about collecting stories?” They said, “Yes, it's a very important part of our fieldwork.” I then asked, “What are you going to do with the stories?” And they said, “Well, we're going to take them back to the museum.” “And then what happens?” “Well, we're going to put them in the archive.” And I said, “What else happens with these?” They said, “What do you mean? That's the point of what we do. We collect stuff. And you know, we archive it.” So at about the same time, I had also been living out in my village. We didn't get many visitors, but when we did, we’d get some expert from the World Bank or USAID, or the UN who would come out and spend a couple of days in this little community working on a project or other. These were trained engineers, they were trained agronomists, they were medical experts. But what struck me, because I was often invited to be an interpreter to talk for them, was that nothing that they were proposing to do would actually work very well. Because they didn't understand the local culture at all. And I was getting very interested in development, and specifically within development, in poverty reduction. [The villagers were] very interesting people. They're just as smart as you and me. The only difference is they don't have any money, and very few opportunities. How could we maybe change that, I thought? None of the things these folks are talking about are going to make much difference, because half of them won't work, and the other half have nothing to do with their lives. Right. Then I met the Belgian anthropologists and I thought, aha. Here's a method for discovery.

Briody: The stories.

Nolan: The ethnographic method, that I could use to enter into the cultural worlds of other people in a useful way. So rather than taking all this information and putting it in the archives, so to speak, I could put it into the project. So that's what I decided to do. I never intended to become an academic. I always wanted to be a practitioner, I wanted to be a development anthropologist, that was my game plan. I started looking around in my last year in the Peace Corps, how do I get educated in this, right? And so like you, I had fairly abysmal scores on some of my [college] tests. But I applied and was successful at getting into three of the four graduate schools in the states that I applied to. But as I read through the materials, I thought to myself, everything here is very hard. And it takes a long time. And there are all these requirements. And they keep emphasizing, you have to do your quals. And then you do your proposal. And then you do this, and you do that, you do the other. And furthermore, everybody on the faculty at these places were specialists in either Native Americans or Mesoamericans, or they were archaeologists. And they said, you have to qualify in all four of these fields in order to sort of get through. And I wrote back, and I said, but I don't want to do that. I want to be a development anthropologist. I'm going to work in Africa and Asia, and help people, you know, have better lives. Oh, no, they said. If you come here, this is what you have to do. So I wrote back and said, Well, I only have to do [those things] if I come there. And I'm not coming. So it suddenly dawned on me -- I'm not a very quick study with these things -- I thought, if you want to work in Africa and Asia in international development, why not go to the seat of empire?

Briody: Exactly.

Nolan: And so I started applying to schools in Britain. That was very interesting. I got into Manchester, SOAS, (the School of Oriental and Asian Studies), and the University of London. I also applied to Oxford and Cambridge. And I can't remember which of them said to me, well, we'll let you in, but you have to take a special diploma first, because you're an American. So I said, “Well, I’m not doing that.” But then I got a Fulbright scholarship to go to the UK. That was what made it possible. I was prepared to go and find a way to pay for it myself, but Fulbright was great. The Fulbright Commission said to me, one school you did not put on your applications was the University of Sussex, and we think you should go there, [although] you can go to whatever school you want to go to; Fulbright will get you into any of these places. But if you want our advice, go to Sussex. So that's what I did. And it was the best training I could possibly have gotten. It was social anthropology, there was none of this archaeology, physical anthropology, just none of it. And furthermore, the folks teaching me had been to these countries that I wanted to go and work in. Some of them had actually been in the British colonial service. And nobody ever, ever said to me, why do you want to be a practicing anthropologist, nobody ever challenged what I wanted to do. I said to my tutor, when I got in, “I’m only here for the Masters, because that's all Fulbright is paying for. Once I'm done, I'm out of here. I'm going to start working.” And he said to me, “Fine. Just a piece of advice. If you could possibly stay for the PhD, that would probably be helpful to you in later years. But you can certainly do what you want to do with a master's degree.” This was so far in advance of this whole MA practitioner thing, it was in 1968 for Pete’s sake. As for the PhD in Britain, it’s possible to get one in three years.

Briody: Yeah. Right.

Nolan: Since I knew what I wanted to do; this was perfect. So I said, “Okay, I'll give it a try.” I started applying for other sources of funding, and got a few. Then I did my doctoral fieldwork back in Senegal [and two years later,] I came back [to the UK]. And, you know, that was it: I was a PhD from the University of Sussex.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: My funding ran out about five months before I was due to present my thesis. I needed a job. I thought I was going to go and work in a development agency, but that proved to be a little harder than I thought. Knowing what I know now, I think I could have done it, but I didn't know enough at the time. And there wasn't that kind of network of practitioners to sort of say, go here, go there. I didn't know about informational interviewing, So I wound up getting my very first job in the University of Papua New Guinea. It was an “academic” job. I'm putting air quotes in it, because I was teaching community development and social development policy, and that's what I wanted. So I thought, all right, here we are. This was a university that was only five years old, and training the first generation of Papua New Guineans. It was staffed mostly by Australians, New Zealanders, and a sort of a smattering of other expatriates, a few Americans, some Africans, some South Asians. I went out there and I was there for four years, and had a wonderful time. I got working on a couple of projects, I taught a lot of interesting students, I made friends. We were there kind of at the beginning, when I went out, it was an Australian territory. I was working for the Australian Government.

Briody: Interesting.

Nolan: Two years in, it became independent. So I saw the country become independent, and I was there for two more years. And then I left. So that was my very first real job. And after that, it was pretty much all development work, contract work, independent work. But first, I did postdoc research in Senegal and at Berkeley.

Briody: After Papua New Guinea?

Nolan: After Papua New Guinea. I wanted to do some more fieldwork on urban migration. I got a Ford Foundation grant to go back to Senegal, to do a year in Senegal, in urban based research. So I did that. Then I went to Berkeley for a postdoc. And then I started working on development projects. I did three or four fairly long-term things. In addition to the four years I was in Papua New Guinea, I did nearly four years in Tunisia. I was director of an urban development project there. I went back to Senegal several times to do short term projects, social soundness analyses and some training and so forth. Then I went out to Sri Lanka to do a couple of years there. And then by that time, it was 1984. And so much time had passed, if you see what I mean.

Briody: Sure.

Nolan: I was married, with a seven-year-old boy. And a number of things happened [in Sri Lanka around that time]. My boss and my old secretary, from Tunisia, got blown up, killed in the Beirut embassy explosion, 1983. The Sri Lankan Civil War started. And a close colleague of mine got taken hostage by the Tamil Tigers, and released unharmed, fortunately, but we all looked around at that point and said, “Okay, maybe it's time to leave.” It's not that it's so dangerous, but it's getting old, I thought, for want of a better word. You get to a point in development agencies, and everybody who's in that business recognizes that it's probably like what you described for [your work at] GM a little bit earlier. You're overseas. At some point, you get good enough and recognized enough. By this time, I was known to a lot of people [in the development business]. I wasn’t famous, I don't mean that, but I was a known quantity. And that's what they want. So you either can stay where you are and keep doing two or three-year contracts, or you do what they call going inside. And you join the UN as a full-time card-carrying member, you join the World Bank, you join USAID. It’s a very rigorous selection process to join USAID, you are appointed as a Foreign Service Officer. You go through a whole battery of interviews and tests and blah, blah, blah, blah. But it's possible to do it and I was offered the chance to do it twice. But I said no, I don't think I want to do that. Because by that time, I had figured out a couple of things. One was, I had set out trying to figure out how to put qualitative social science into development planning and [by now] I'd figured out how to bring my insights as an anthropologist into project planning. I'd learned a lot about project planning, and about how to train people to do that, and so forth. Along the way, I had worked with a lot of people like engineers and doctors, and agronomists, so I had developed that co-thinking conversation, and so we were all working [together], you know. Teamwork was what I did. But I also got fascinated with how big agencies think about what they're doing. Because I realized that I had started at the grassroots level, as a Peace Corps volunteer living in a grass hut.

Briody: Yeah, exactly.

Nolan: I knew how to do that. And I could speak local languages and everything. But I had no particular desire to hang around in a village for the rest of my professional life and do one round of that kind of field work one after another. So I figured out how to do projects at the ground level, and then I figured out how to plan projects, and then I figured out how to design programs. So this was going in a sort of an upward trajectory if you see what I mean, more and more abstract in some ways, but more and more powerful as a way to get systems focused.

Briody: Systems focused more.

Nolan: And finally, I started realizing that, yes, it was very important to understand what the locals thought from the emic perspective, the local practices and all of that, but what was also really important to understand was what the World Bank thought about, because they were the ones that were allocating the money, they were the ones that were making the resources available. And so as things like structural adjustment, which came in about the time Ronnie Reagan got elected, kicked in, I thought, these guys in Washington and Paris and London are pulling the strings, and influencing how things happen. It's no longer just a matter of local cultures. They don't care about local cultures very much; they care about moving large amounts of money. How do these people do that? How do they think about it when they do it?

Briody: Right.

Nolan: And so it became fascinating to me to start looking at organizational culture. How does USAID think about what it does? How does it learn? How does it fail to learn? What does it do with what it learns? I had already been working either in or with USAID for about five years, I knew how those guys thought. Then, shortly after I got back to the States, I took a nine-month assignment as a World Bank consultant. I moved to Washington, and I did policy analysis for the bank. And so now, I understood at least a little more than I did before, about how the World Bank thought.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: I never had a chance to work extensively or, or intensively with the UN, but I did a few literacy-related things with them. So I had a pretty good idea about that. And that became my main focus -- looking at agencies in terms of how they did things. That didn't require a whole lot more fieldwork than what I'd already done.

Briody: But who was your customer at that point?

Nolan: In 1984, when I came back [to the US], I needed a job. And I didn't think there was a whole lot of call for a development anthropologist in the United States. What I did think was that I had a pretty good shot at getting a university job, because even though I'd been a practitioner all this time, I'd written articles, and had a book under contract.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: I looked enough like an academic duck, right, to sort of pass muster at least. And so I was lucky, I got a job at Georgia State University.

Briody: Before you go on with that, I wanted to ask you what was the focus of the postdoc at Berkeley?

Briody: Before you go on with that, I wanted to ask you what was the focus of the postdoc at Berkeley?

Nolan: I had done this this this year of research in urban Senegal, in the city of Tambacounda, looking at ethnic migrants coming in, and what happened to them.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: And I realized that I had a very interesting story to tell, if I related my previous rural based fieldwork to this urban work. So I applied for a postdoc to go to Berkeley and have a year to write it up. It turned out to not be quite a year, but you know how those things go.

Briody: I see.

Nolan: I got the first draft of the book done. It was very hard for me actually to learn to write a book. Nobody was helping me for one thing. And so a few kind editors at various academic houses took me under their wings.

Briody: That's so important. Yeah.

Nolan: They said, “Son, this isn't going to fly. But here's what you can do to make it better.” And fortunately, that worked for me. Dean Birkenkamp at Westview picked up the book and published it and that was my first academic book.

Briody: I see. Okay, yeah.

Nolan: So I spent my time in Berkeley doing that.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: But I also spent time networking. Now, I was a little more savvy than I had been before. So I sort of branched out. Christine, my wife, and I both made contacts in the Urban and Regional Planning school at Berkeley, and that's how I got my next job.

Briody: In Washington?

Nolan: In Tunisia. This was after the postdoc, in 1978. Later, I got my job in 1984 in Georgia through Bill Partridge, who was the chair of the Department of Anthropology there at the time. He was very interested in turning this department into an applied anthropology program. And he was a little bit ahead of his time.

Briody: Yes, he was.

Nolan: Bill and I had never worked together, but he'd been employed by Harza. And I’d had a contract with Harza, at one time.

Briody: Who are they?

Nolan: They're an engineering firm in Chicago.

Briody: I see.

Nolan: They do a lot of international stuff.

Briody: H-A-R-Z-A

Nolan: So Bill hired me in 1984 to be an assistant professor at Georgia State. Well, let's just say that Bill's efforts to turn that department into an applied department didn't work. And this was a seven-person department.

Briody: Yeah, too early, maybe.

Nolan: And within a couple of years, I had left, Bill had left, and two other people had left.

Briody: Okay.

Nolan: And the department basically went into receivership. There’s a story there, but it's not worth bothering with. What I had decided by that time, was that academic life was probably not for me. I found it, frankly, to be quite boring. The politics of it were very strange, with people focused on things that I didn't think were important. And occasionally, things got rather vicious. I watched this, and I thought, I don't really want to live like this. This isn't me.

Briody: Sure. Right.

Nolan: What I did then was start looking for two things. One was multidisciplinary programs. [The second was a non-academic job in a university, in administration] I still believed in educational institutions, but I wanted a multidisciplinary program where I could work with students who were either on their way overseas, or who I could get overseas, to have that kind of epiphany that I had in the Peace Corps. I did three very productive years at the School for International Training in Vermont, which for my money is one of the best institutions we have in the country for training young people to be in the development and humanitarian, social justice, human rights arena.

Briody: Where is it located?

Nolan: It's up in Brattleboro, Vermont. It’s not a scholarly institution, but it’s a fully accredited master's program. Nobody's ever heard of it, you know, at Purdue, but everybody in the development business has heard of it. And if you're an NGO, you've heard of it. That's where they got their best people. So I was up there for three years, and I had a wonderful time. I worked with people getting ready to go overseas, debriefing them when they got back, and working with them on their master's thesis project. It was wonderful. Then I went to the University of Pittsburgh, where I ran their international executive training programs for six years in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs.

Briody: Interesting.

Nolan: I taught in anthropology courses there part of the time, but my main job was traveling around the world, making connections between Pitt and these other places, and bringing people like Russians, Saudi Arabians, Africans and whoever, into Pitt and training them. Or going overseas and doing training [there]. We had some really interesting times with that. And it was very anthropological, because everything we did had a cross cultural component to it.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: I was training faculty at Pitt in how to do these things in unfamiliar environments. I was training incoming people. [I was designing cross-cultural orientation programs, focusing on things like] how to avoid getting arrested in the United States or whatever. I left Pitt after six years, and went out to Golden Gate University to be their first and probably last Dean of International Programs. I wound up working for a man, let's just say, who resembles Donald Trump in many ways. And I started becoming acquainted with the psychological literature on narcissistic personalities. He was fired, but I and most of his senior staff all succeeded in escaping the place before that happened. So I was there for only three years. It was interesting, but it didn't amount to a hill of beans in terms of institutional impact. You just couldn't get anything done under this guy. From there, I went to the University of Cincinnati where I was the Associate Provost for international programs. And that was very interesting. We did a lot of things and after six years, I'd sort of plateaued. I realized that I had gotten about as far as I could go, [and then] this job opened up and I came up here [to Purdue, as Associate Provost for international programs]. And when I got to be 65, Purdue said, according to the university policy, you have to step over to the faculty now.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: So now, at the end of my career, I am finally an academic.

Briody: [laughs] Who would have thought.

Nolan: It's not what I set out to do. I have a great deal of respect for academic anthropology, you know that. I'm comfortable with it. But it isn't what I started off to do. And I think that my perspective, like yours, is as a practice-based person. I mean, I practiced for a long time, but you've done it for far longer. It changes the way you look at everything in your discipline. I enjoy it and I think my students appreciate it. I am worried a little bit about what our discipline is or isn't doing to sort of transform itself. But I'm having I'm having a good time with it now.

Briody: Yeah. Well, looking back on your whole career, can you imagine it being different?

Nolan: Yes, I can imagine that. And I think this is true of most of us. You look back, and you realize that there were choice points that maybe you didn't even know were choices at the time, if they had worked out. So for example, if I had not had that conversation with my advisor that spring morning, I might have gone and joined the army.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: I don't know, I might be a three-star general today.

Briody: Right. But you listened to him. Listen, and process. And I think that's an important lesson.

Nolan: But at every stage of our professional lives, there's this interplay between what one of my colleagues calls agency and contingency. Agency is what you do, and contingency is what happens to you. And you have to sort of be able to, you know, integrate those in some way.

Briody: Right. Well, and you also have to have Plan B.

Nolan: Yeah. And I always did have a plan B. I'm on the Fulbright committee here, and we interview applicants. And I always say to them, if you don't get the Fulbright, what are you going to do? And some of them kind of go, oh, well, and then they -- it's clear that Fulbright is kind of like a prize that they want. And if they don't get it, well, they just go do something else. But some of them say, “No, what I want to do overseas is actually my heart's desire, and I'm going to find a way to do it. Even if I don't get the Fulbright, I'm going to do this. I'm going to get there.” Yeah. And that was kind of the way I was with education in Britain, I decided that I might not want to go to school in the United States. It might have turned out fine, but I just had a sense. No, I don't want to go that way.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: I want to go this route instead. And even if I don't get a scholarship, I'll do it. I'll find some way to do it.

Briody: Right? Well, it sounds like you know, at a pretty early age, you were pretty globally oriented for a kid from upstate New York. And I can say that because I was just in the neighboring state.

Nolan: God knows why. I don't know. Because there wasn't much in my town. That was global.

Briody: Right? I know.

Nolan: Except the books in my grandmother's basement, and my uncle's journals and diaries.

Briody: Well, and for me, I think it was my mother who always emphasized the importance of speaking to everyone, not just select people. Something I think about quite a lot is a couple that she knew who were older than she, and they were deaf, and one was mute. And my mother always stopped to talk with them. Even though communication was difficult, and they were so appreciative, and I could see the responses in their faces. So, you know, I grew up with this orientation of you talk to everybody.

Nolan: You know, it's funny you say that. My dad gave me exactly the same advice. When I was in high school, I was really looking forward to a summer of doing nothing, when I was like 15 or 16. And my dad disabused me of that right away, and he said, “No. “You're going to go out, and you're going to go to work. You're old enough to work and you're going to go to work.’ And he said this to me, because I had high school buddies my age who, who were working, quote, unquote, one of them was a lifeguard, you know, at the local pool, and another one was in his dad's office making coffee and running photocopies for people. That was his summer job. My dad said, “No. You want to get out and work with real people doing real jobs.” So my first job in high school was as a garbage collector. I got up at three o'clock every morning, whether I'd been out partying the night before, whether I wanted to or not, I got up and we collected the damn garbage, you know, in Syracuse downtown. And my next job was as a carpenter's apprentice, and my next job after that was in a General Electric assembly line making electric can openers. All that stuff that you heard about and learned about on the line? Absolutely, I mean, that was that was my summer experience. I worked with these guys. And my dad said, “You need to do that, you need to understand how ordinary people live. Because you're going to go to college, you're probably not going to turn out that way. But you need to remember.”

Briody: You need to understand other people's perspectives.

Nolan: And you know, and he kept saying to me, get to know everybody. Dance with the girls that aren't so pretty, you know, at the prom, stuff like that.

Briody: Exactly.

Nolan: It's the same sort of message overseas. Once I learned the language in Senegal, man, I would talk anybody's ear off. I mean, I would just spend all day talking to these people. I found out that what they talk about, it isn't that exotic, it’s just normal stuff. “Here come the cows.” “Yes, the cows are coming.” Senegalese farmer talk. But we were doing this is a language that nobody ever heard at home.

Briody: Normal stuff. Funny. Oh, gosh. You know, one of the questions that we didn't quite cover was when in working in international development projects and programs. Were there particular projects you found most interesting? Oh, yeah. gosh. Could you maybe give us an example of one?

Nolan: Sure. The Tunisian project was the most challenging one I ever did, because it was complicated. It had half a dozen moving parts. It was an integrated urban upgrading project. IIPUP. [Integrated Improvement Program for the Urban Poor] That's what it was called. It was a pilot project.

Briody: And what was it doing?

Nolan: It was a joint project between USAID and the World Bank. My part was USAID; World Bank funded my colleague’s part. He was a Tunisian architect, named Mohammed Abdullah. There was a slum community on the on the outskirts of a salt lake [sebkhat in Arabic] at the edge of Tunis, and there was this sort of dirty squatter settlement that had grown up around it. Very insalubrious, as they would say. It used to flood seasonally, you know, so the upgrading project had two components, physically upgrading roads, sewers, drainage, electric lights, piped water. Then there was the socio-economic component, which was my thing, health education, small business development, women's enterprise development, literacy programs, all these different things. And I had to coordinate all this with a bunch of Tunisian agencies that weren't used to working with each other very well. And weren't used to working with foreign entities, either. But you know, we made it work. I mean, it worked, and I got a lot of help from a lot of good people. I ran a staff of 25 Tunisians, talk about herding cats. These folks are all independent minded Arabs. Not to be culturally stereotypical, but Arabs are very independent minded people, they go and do what they're going to do. And you need to gain trust, you need to get a bond going and everything. So I had to work really hard to establish myself as somebody that could be worked with. I was there for nearly four years, and I gained a great appreciation for Arab culture, for Tunisian national culture, for history, for the religious sorts of influences on how communities work, and so forth. I learned a lot. That was where I probably learned the most about project design and program management.

Briody: Right. Right.

Nolan: And so it was a real testing time for me. I mean, we learned a lot of this stuff through trial and error. My whole team and I did, and we all did it together. And sometimes we'd face a setback, but most of the time we succeeded.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: So that was a good project.

Briody: Have you ever been back to see what has become of that area? And what was it like?

Nolan: Yes. It's unrecognizable today. It's great. It's thriving. But it hasn't turned into the exclusive neighborhood of Tunis.

Briody: Right, right.

Nolan: Of course, the trees are grown, the streets are clean. This was a place where people had no title to their land. They were living in very substandard conditions. So the first thing the project said was we need to survey the area and we need to assign everybody their plot of land and say that it belongs to you.

Briody: So they were going to give it.

Nolan: That was a big part of the project. And they did that. And so people then started to improve their houses, of course, which they weren't really going to do before, because they thought any minute now, the man is going to come and knock it down, you know, but now that that wasn't going to happen. And the businesses are working there and so forth. Was that all because of us? No, but it was a concerted effort with a whole bunch of people who took it seriously.

Briody: Sure.

Nolan: And that was really neat. I liked that.

Briody: You know, also, I wondered about advice that you would give to somebody who was just starting out at some whatever level masters level, PhD doesn't matter. What, aside from actually going and being there, how do you make inroads into international development agencies or allied organizations? Is that you mentioned how it was difficult.

Nolan: Well, this is going to be a case of do as I say, not as I do.

Briody: Okay, fine.

Nolan: How would you do this? This whole business of informational interviewing is so important for understanding because the thing that academic life seems to instill in people is a self-absorption. It's all about me, my research projects, my publications, my this, my that. Practice work is never about that. It's about you in relation to other people. And so if you don't know who they are and what they want, how can you possibly come across to them as somebody useful? What I say to people is, go down to Washington, go down to New York, go down to Atlanta, go to San Diego to LA, wherever, locate some of the organizations that you have heard about, that you can research online. The Web is great for this. You know, type in “human rights programs in Pakistan” and up pop half a dozen organizations. And now what you want to do is contact those places for a half hour chat with a program officer, not the HR people, but the program person who's in charge of how this works in a particular setting. And you start asking a set of fairly smart questions. It’s not an interrogation; you're asking for advice.

Briody: Sure. Right, exactly. People are willing to do that.

Nolan: You're not asking for a job. If you start coming in saying I'd like a job, they're going to think of all kinds of reasons not to employ you.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: They don't know you. If you ask for advice, of course, they'll say, sure.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: People just respond that way. And so it's, you know, [you ask them things like] what do you do, what's the philosophy that guides your work here? What's it like to work here? What kinds of qualifications do you look for in the people that you hire? And if they say things like, well, everybody is really a graduate of an Ivy League university, and they've all majored in economics, now you know something about how you stack up in relation to that.

Briody: Okay.

Nolan: I can tell you very exactly what it was that got me most of my jobs, starting out. It was my ability to speak languages. They were not hiring me because I was the best anthropologist, they didn't care. That was just a category that they had to fill: social scientists. It could have been a sociologist.

Briody: It was a checkoff, right,

Nolan: But I could operate in the local language. I could do it.

Briody: And it seems like you're a bit of a polyglot.

Nolan: Well, possibly, but I'm just saying, and I stress this with students: learn another language. It will never hurt you. And it will often help you because you need to be positioned outside the mainstream, if you're going to compete effectively with other people. Anthropologists have grown up thinking we're special. You're not so special, I'm sorry. There's lots of people who can do ethnography, all you have to do is go to an EPIC meeting to find that out. And there are lots of people who know about corporate culture. But if you can do this in German, or in French, that makes a difference. You're the one they're going to send. So you do your informational interviewing, and then you write your resume. Because now you know what you need to say, to get into the categories that they're looking for. And they'll say, call that person in.

Briody: I think there's one other question I do want to ask and that has to do with SfAA. How can an organization like SfAA meet the needs of its members who are interested in international development? And it doesn't specify whether it's a student or not?

Nolan: I would have to say that international development appears to have gone to some kind of eclipse in the last few years. I think the heyday of this was in the 70s and 80s. And by the 90s, shifts had already started to take place. There was a shift in development programming toward policy-based lending, for example, and there was a retreat from the field. I can give you a 30 second history of how this worked. Back in the early 1960s, USAID people were actual muddy boots engineers. That is where the term the ugly American came from. Everybody today thinks the Ugly American is the boorish tourist. It is not. The Ugly American was a guy named Homer Atkins from Pittsburgh. He was an engineer, and he was sent out to a mythical country in Southeast Asia. This was in Burdick's book, The Ugly American, [Editor: Eugene Burdick and William J. Lederer were the authors of this bestselling political novel published in 1958. It had a significant impact on President John Kennedy and his idea of the Peace Corps.] Atkins was the guy who learned the local languages, he and his wife lived in the village. He was the one who figured out how to make the pump work using local materials. He was a hero, for Pete's sake. And that's what a lot of those early AID guys were like, they lived in trailers out beside the rice paddies. And then Vietnam happened, the war happened, and the whole thing got bloated and bureaucratized. And AID started basically wholesaling development work out to mercenaries, like me, contractors.

Briody: Right.

Nolan: They didn't do their own work anymore. They stayed in the office, and they hired people like you and me to do this work. And we learned a lot, but they didn't learn very much.

Briody: And then what happened?

Nolan: And then all of that sort of dried up, but they didn't go back into the field. They had established bureaucratic niches, and they still hire people.

Briody: In subcontract.

Nolan: Yeah. We're starting to fight our wars this way, with Blackwater and so forth. There was this period of time when the development industry realized it needed a lot of social knowledge to run, like integrated development projects, and so forth. And they hired a whole bunch of anthropologists to do that, guys like me, guys like [Bill] Partridge, a whole bunch of people. And then all of that kind of went away. There are still a lot of people working in development, but not as many as before and they're not as influential as before. And you could talk to people like Mike Cernea, about how he shared that he's, he's not happy with the way the [World] Bank has changed. So that's it in a nutshell. I would say, you know, if you want to do it, it's a great career. But here's the thing I say to people: no matter what domain of anthropology of practice you're in, there is a need for social knowledge. That's the main thing. And that's your forte. You can find that stuff out, you know how to find it. And more than that, you know what to do with it. And that will get you your job, whether it's in development or health or business or on the assembly line or whatever.

Briody: Hey, thanks, Riall. Good. Appreciate it. Okay.

Further Reading

Lederer, William J. and Eugene Burdick. 1958. The Ugly American. Norton.

Nolan, Riall. 2002. Development Anthropology: Encounters in the Real World. Westview Press: Boulder. Colorado.

Nolan, Riall. 2003. Anthropology in Practice: Building a Career Outside the Academy. Boulder CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Nolan, Riall. 2017. Using Anthropology in the World: A Guide to Becoming an Anthropologist Practitioner. Oxford, UK: Routledge. .

Cart

Search