An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

From the Editors

Times of Privilege; Lives of Survival

Orit Tamir and Jeanne Simonelli

This has been a month of post COVID contradictions. As a seasonal Park Ranger, I (Jeanne) answered a call for those who might want to do presentations about the Park Service on a Royal Caribbean cruise through the Alaska inland passage. Never one to turn down anything free and with Alaska on my bucket B list, I applied. Three months and four PowerPoints later, I set sail from Seattle on a ship holding 4000 purportedly Covid free persons. Since the trip was for two, I was accompanied by a Park Service friend with a similar taste for complimentary adventure.

This has been a month of post COVID contradictions. As a seasonal Park Ranger, I (Jeanne) answered a call for those who might want to do presentations about the Park Service on a Royal Caribbean cruise through the Alaska inland passage. Never one to turn down anything free and with Alaska on my bucket B list, I applied. Three months and four PowerPoints later, I set sail from Seattle on a ship holding 4000 purportedly Covid free persons. Since the trip was for two, I was accompanied by a Park Service friend with a similar taste for complimentary adventure.

I'd never been on a cruise and figured that between watching the passengers and visiting Alaska it was an anthropologist’s dream. Cruise ships are floating hotels, complete with multiple swimming pool complexes, opulent restaurants, massive buffets, casinos and clubs. Once on the boat the multitudes disappear into both these public spaces and eight decks of cabins. Super spreader Covid crowds are only visible when getting on and off in a port.

My presentations took place on a huge stage in an auditorium that dwarfed any of the classrooms or campgrounds where I’ve talked. I was tempted to launch into “Dancing Queen” or some other 70s disco hit, with appropriate footwork. The shows were relatively well attended and then rebroadcast on the cruise’s closed-circuit TV. Recognized both on ship and off, it was Andy Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame.

My presentations took place on a huge stage in an auditorium that dwarfed any of the classrooms or campgrounds where I’ve talked. I was tempted to launch into “Dancing Queen” or some other 70s disco hit, with appropriate footwork. The shows were relatively well attended and then rebroadcast on the cruise’s closed-circuit TV. Recognized both on ship and off, it was Andy Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame.

The ship’s staff was responsible for making passengers feel that they were truly on vacation. Comprised of Filipino, Caribbean, and other hardworking nationalities, they seemed to never get a rest. In fact, they work cruise to cruise and only pause when the ship is in port between groups. They are dependent on tips, and each adult visitor pays $14.50 per day. It doesn't come out to very much.

Cruising with the family is an upper middle-class activity. While it is not hugely expensive as a base price, if you purchase drink and food packages the cost skyrockets. Just having appropriate clothing to participate in what might be called a floating prom night adds to the final amount. It is about privilege, as is all ability to take a vacation.

Cruising with the family is an upper middle-class activity. While it is not hugely expensive as a base price, if you purchase drink and food packages the cost skyrockets. Just having appropriate clothing to participate in what might be called a floating prom night adds to the final amount. It is about privilege, as is all ability to take a vacation.

The ship’s 4000 guests ranged from newlyweds to retirees, families with young children and thirty somethings traveling with the grandparents for a special trip. Sometimes the children paid for the elders. Sometimes it was the reverse. Interestingly, often it was the small number of African American families who were multigenerational. For the bulk of the passengers the previous two years seemed to be just a memory.

The seas were calm and uneventful for my seven-day stint. Since ending from my Royal Caribbean week Google has been bombarding me with cruise ship sagas. My ship, Ovation of the Seas, was forced to reroute following a landslide in Skagway. A Norwegian Lines ship hit an iceberg. While no Titanic it did return to Seattle. And a Carnival Lines brawl was broken up by the Coast Guard.

After returning home, I washed my clothes, tested negative (again) and repacked my suitcase for a short visit to Chiapas, Mexico. Because of the Covid pandemic, six years had passed since the last trip to see both my Zapatista friends and some of the North American anthropologists who have lived in San Cristobal de las Casas for decades.

In 2016, the riverside community of Cerro Verde showed signs of official ties to the outside world. A cable TV connection, fitted with at least 20 signal splitters, supplemented the radio and one station TV of earlier years. But the pandemic brought the internet, smart phones, Facebook and What’s App, keeping communication alive.

Keeping the cruise ship disco theme going, the song accompanying this trip was “I Will Survive”. There has been no vacation for the matriarch and patriarch of this group; for the children now grown into parents. There has been travel. A few of the men are in the US, working in construction, paying off the Patron and sending what they can back home. New houses are clustered into the existing plot of land, some resembling what was seen while out of the country.

It was no vacation for the campesinos, whose coffee crops suffered their own pandemic and had to be replaced by new resistant strains. In 2022, these are young, healthy and vibrant.

The expanding families are also doing relatively well, surviving. I was concerned that the jungle Zapatista communities and Caracoles (administrative units) would, like those in the Chiapas highlands, have refused the Covid vaccines being offered. Highland groups distrust the government to such an extreme that they are certain the vaccines are poison. While the lowland groups don’t trust the government, they have always found ways to launder a needed resource and have accepted vaccines for years.

The expanding families are also doing relatively well, surviving. I was concerned that the jungle Zapatista communities and Caracoles (administrative units) would, like those in the Chiapas highlands, have refused the Covid vaccines being offered. Highland groups distrust the government to such an extreme that they are certain the vaccines are poison. While the lowland groups don’t trust the government, they have always found ways to launder a needed resource and have accepted vaccines for years.

The women particularly are all vaccinated, receiving 2 regular and one booster from the promoturas de salud. While the pandemic kept most activity curtailed and local, the Zapatista organization responded by creating smaller Caracoles so that people could gather. Full scale meetings had just begun again. After a brief pause, la lucha sigue. The struggle continues.

The women particularly are all vaccinated, receiving 2 regular and one booster from the promoturas de salud. While the pandemic kept most activity curtailed and local, the Zapatista organization responded by creating smaller Caracoles so that people could gather. Full scale meetings had just begun again. After a brief pause, la lucha sigue. The struggle continues.

During the course of the pandemic, the community patriarch passed away. Facebook made it possible to be present at the funeral, where an EZLN banner covered the casket. His wife, born somewhere near 1920, is still alive. She is an extraordinary example of strength, a role model who looks today as she did twenty years ago.

Returning to the places where people welcomed us into their homes and lives so many years ago is a critical part of practicing anthropology. Sharing our lives and families; changes, disasters, and renewals is what makes the learning process both complete and continual. Would I go on another cruise? Not likely. Will I go back to Chiapas? It will be a privilege to do so.

A persistent question asked by my Zapatista friends throughout the visit was what caused the fires raging in New Mexico? Explaining the role of drought, the Forest Service, prescribed burns, and root fires was not easy. Living in New Mexico and with ties to New Mexico Highlands University, Orit was far better equipped to answer that query.

Until this summer, and at the risk of showing my (Orit) age, I used to associate Earth, Wind, and Fire with a rock band. During the Spring and early summer these words got a whole new meaning in Northern New Mexico – the place I call home. “Thanks” to an ill-advised and blundered “prescribed fire,” northern New Mexico’s Hermit Peak and Calf Canyon fires, both caused by the US Forest Service (the Forest Service admitted responsibility), merged, and grew out of control. The Calf Canyon/Hermit Peak Fire scorched over 341,000 acres, transforming the biotic and sociocultural environment of Northern New Mexico.

The Hermit Peak/Calf Canyon Fire is the largest fire in New Mexico’s recorded history. It impacted a region (mainly Mora and San Miguel Counties) that is also a Hispano homeland (upper Rio Grande Valley and adjoining uplands of Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado). Small Hispanic villages and ranches pepper the ponderosa forested mountains and fertile valleys that Hispanics, many of whom can trace descendants in the region to the Conquistadors – settled centuries ago. They still use the ancient acequia system (a community-based watercourse in New Mexico that is used for irrigation of traditional crops that simultaneously honors cultural heritage) that requires considerable inter- and intra-community cooperation. The farms are small-scale farming, and some also graze their cattle in open range or keep a few goats and sheep for household use. More recently, non-Hispanic moved to this beautiful countryside, living side-by-side the Hispanic population. The Calf Canyon/Hermit Peak Fire scorched this beautiful mountainous rural area, ruined lives, and has threatened a unique regional culture.

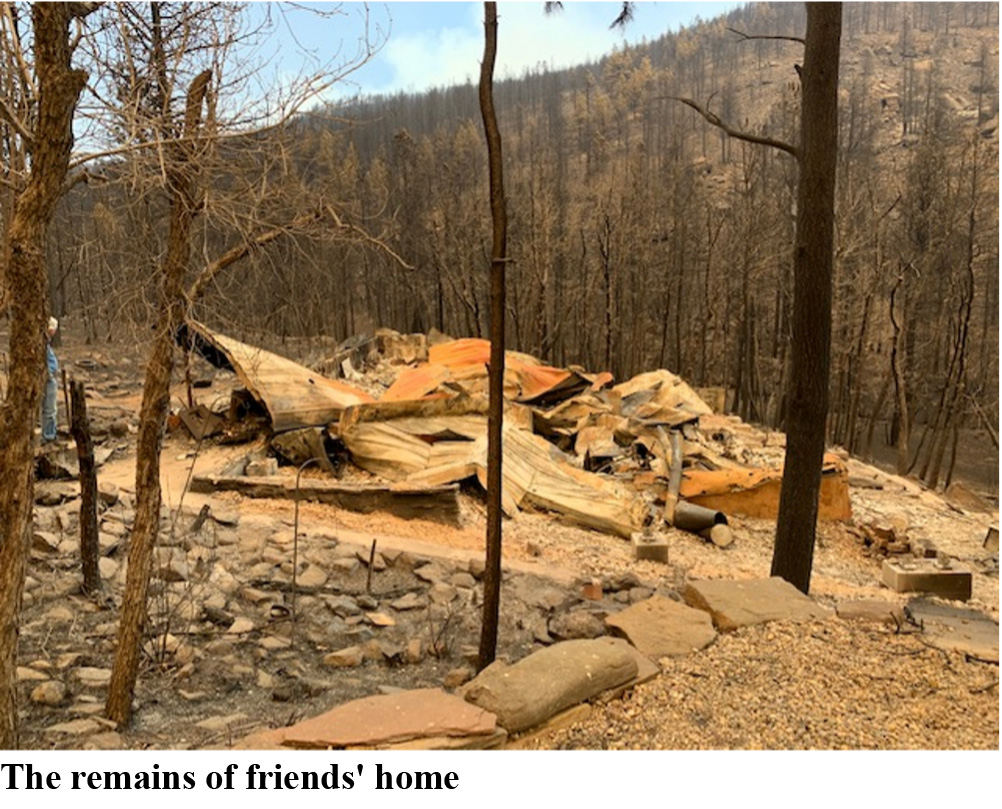

The fire destroyed hundreds of homes and thousands of people had to evacuate. I have friends and acquaintances who lost everything, and others who found themselves displaced. Most of the folks impacted by the Calf Canyon/Hermit Peak Fire have lived in the region for centuries. Some intermarried with Native Americans, and many speak an archaic form of Spanish that can be heard at New Mexico Highlands University (where I was faculty until my recent retirement) and at local businesses. These are the people who developed the unique regional arts and crafts that are celebrated every July in the Traditional Spanish Market in Santa Fe.

The fire destroyed hundreds of homes and thousands of people had to evacuate. I have friends and acquaintances who lost everything, and others who found themselves displaced. Most of the folks impacted by the Calf Canyon/Hermit Peak Fire have lived in the region for centuries. Some intermarried with Native Americans, and many speak an archaic form of Spanish that can be heard at New Mexico Highlands University (where I was faculty until my recent retirement) and at local businesses. These are the people who developed the unique regional arts and crafts that are celebrated every July in the Traditional Spanish Market in Santa Fe.

How did this happen? The Forest Service was using dated methods and little accurate data to start the prescribed burns. The high winds of April and May (an annual predictable occurrence) followed and the Hermit Peak Fire exploded out of control, merging with the Calf Canyon Fire. For weeks the normally blue cloudless sky with pristine dry clean air was full of smoke and ash. Efforts to contain the huge fire went on for weeks. Then the monsoon rains and downpours caused mudslides, and flashfloods in the vast burn-scar region. Dr. Jennifer Lindline, an environmental geologist that heads New Mexico Highlands University (NMHU) Water Resources program, with two interns, Megan Begay and Letisha Mailboy, (both Diné) have been monitoring the Upper Pecos River weekly since 2019. Their study gained new significance as the Pecos River filled with soot and debris from the fire (for more about danger to water in northern New Mexico see the excellent article in the Santa Fe Reporter that features their research: https://www.sfreporter.com/news/coverstories/2022/07/13/the-fire-the-flood-and-the-future/).

How did this happen? The Forest Service was using dated methods and little accurate data to start the prescribed burns. The high winds of April and May (an annual predictable occurrence) followed and the Hermit Peak Fire exploded out of control, merging with the Calf Canyon Fire. For weeks the normally blue cloudless sky with pristine dry clean air was full of smoke and ash. Efforts to contain the huge fire went on for weeks. Then the monsoon rains and downpours caused mudslides, and flashfloods in the vast burn-scar region. Dr. Jennifer Lindline, an environmental geologist that heads New Mexico Highlands University (NMHU) Water Resources program, with two interns, Megan Begay and Letisha Mailboy, (both Diné) have been monitoring the Upper Pecos River weekly since 2019. Their study gained new significance as the Pecos River filled with soot and debris from the fire (for more about danger to water in northern New Mexico see the excellent article in the Santa Fe Reporter that features their research: https://www.sfreporter.com/news/coverstories/2022/07/13/the-fire-the-flood-and-the-future/).

In Las Vegas, New Mexico, a town of 13,000 that is home to New Mexico Highlands University, Luna Community College (LCC), and the United World College (UWC), the fire forced the evacuation of many residents as well as LCC and UWC and threatened the town’s watershed. NMHU had to postpone commencement. Trees and other plants that normally intercept rainfall burned, leaving nearby hillsides and the Gallinas River that supplies drinking water to Las Vegas and vicinity exposed to contamination. Most recently, on July 29th, Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham issued an emergency declaration for Las Vegas, New Mexico because the city’s water supply has been threatened by flooding from the Hermit Peak/Calf Canyon Fire. There is enough drinking water for less than 50 days.

The Calf Canyon/Hermit Peak Fire brought a host of long lasting sociocultural and biotic consequences to Northern New Mexico. A few are predictable: people who lost homes may have to wait many months, even years, to rebuild. Some people may never return and will take with them chunks of a unique culture. For those who will return and rebuild, the biotic environment will be very different, even unrecognizable. Vast areas of Ponderosa forest were burned, and current generations are not likely to see the forest rejuvenate. Moreover, regional familial and traditional practices that endured multiple hardships over the centuries, were severely disrupted. Mudslides, flooding and contamination from ash, debris, and fire retardants chemicals will have long lasting impacts on the region’s already strained water supply, and compound the threat to sociocultural and biotic regional fiber.

The Calf Canyon/Hermit Peak Fire brought a host of long lasting sociocultural and biotic consequences to Northern New Mexico. A few are predictable: people who lost homes may have to wait many months, even years, to rebuild. Some people may never return and will take with them chunks of a unique culture. For those who will return and rebuild, the biotic environment will be very different, even unrecognizable. Vast areas of Ponderosa forest were burned, and current generations are not likely to see the forest rejuvenate. Moreover, regional familial and traditional practices that endured multiple hardships over the centuries, were severely disrupted. Mudslides, flooding and contamination from ash, debris, and fire retardants chemicals will have long lasting impacts on the region’s already strained water supply, and compound the threat to sociocultural and biotic regional fiber.

Perhaps it is time to put people first and develop fire management methods that correspond to climate change, water sources, and the needs of local cultures.

Cart

Search