An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Bruno Pereira, Indigenist

Indigenous-rights advocate Bruno Pereira, 41, was killed in June 2022 while traveling in the Javari River Valley of western Brazil with British journalist Dom Phillips. Local fishermen allegedly murdered the two men because of their work exposing illegal activities by loggers, ranchers, prospectors, drug traffickers and other trespassers in Indigenous territory.

Pereira was formerly head of the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) division charged with protecting isolated Indians. He was removed from that post in 2019, after Jair Bolsonaro became Brazil’s president with the support of exploiters of the Amazon and other endangered areas of the country.

Pereira moved to the remote Javari region to collaborate with Indigenous groups that are trying to protect their land from invaders. He joined Phillips to investigate the region for a book Phillips was working on, How to Save the Amazon.

“Bruno was the new generation” of sertanistas, backwoods explorers and Indigenous allies, according to former Brazilian environment minister Marina Silva. “He was carrying the torch forward.… And suddenly you have that generation being cruelly killed.”

The son of middle-class professionals, Pereira was born in Recife, the capital of the northeastern state of Pernambuco. Holidays in the Mata Atlântica on Brazil’s coast gave him an appreciation of nature. In 2004 he worked in a reforestation program at the Balbina hydroelectric dam in Amazonas state. Several years later he went to work for FUNAI, which is responsible for “protecting and promoting” the country’s estimated 235 Indigenous tribes. Since Bolsonaro assumed office in 2018 FUNAI has been systematically undermined and underfunded.

Pereira focused on remote Indigenous groups that had little or no contact with white society. Because many of them live in the Javari Valley, Pereira moved there. He formed a bond with the Indigenous people in and around the town of Atalaia do Norte and learned to communicate in five Indigenous languages, Kanamari, Marubo, Matses, Matis and Korubo. Indigenous leaders accepted him as part of their community.

With Bolsonaro’s encouragement, loggers, ranchers and prospectors were invading the Amazon rain forest in increasing numbers. Pereira destroyed their equipment and burned their boats. Forced out of his post at FUNAI, he returned to Atalaia in 2019 and joined forces with Indigenous NGOs, principally the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (Univaja) and the Observatory for the Human Rights of Isolated and Recent Contact Indigenous Peoples (OPI). He provided them with surveillance equipment and raised funds on their behalf.

In Atalaia Pereira met his second wife, Beatriz Matos, an anthropologist who was studying the Matses tribe for her doctorate. Pereira leaves three children and numerous Indigenous admirers, some of whom led the search for Pereira’s and Phillips’ bodies after Brazilian police and military failed to find them.

Pereira and Phillips are among hundreds of Indigenous allies who have risked—and lost—their lives to protect Brazil’s most threatened people.

* * *

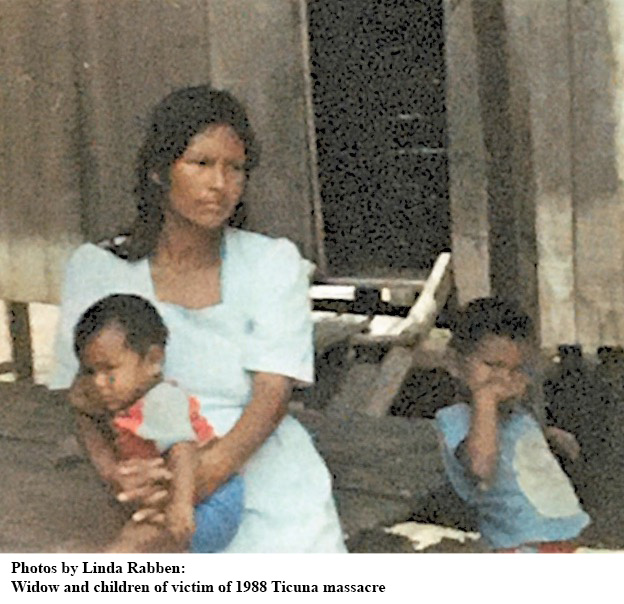

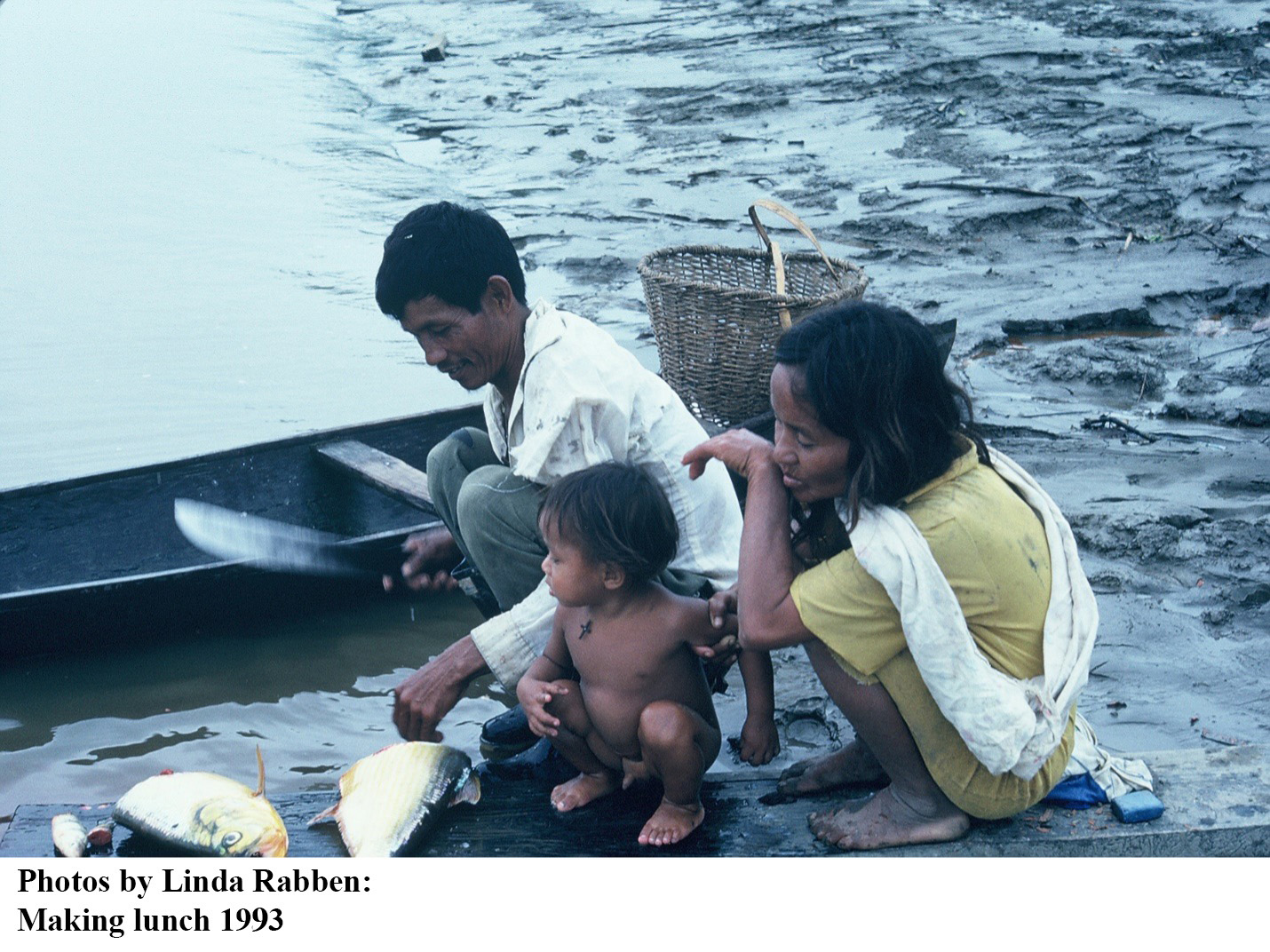

I didn’t know Bruno Pereira, but I did meet and write about people like him in my book, Brazil’s Indians and the Onslaught of Civilization. As part of my work on Brazil for Amnesty International, I visited the Javari River Valley in 1993, to visit Ticuna Indians who had lost 14 men and boys in an ambush by a land-grabber. My hosts put me up in the town of Benjamin Constant, where they told me it wasn’t safe for a supporter of Indigenous people to stay in the only hotel. Instead I stayed at the home of a Brazilian anthropologist who was helping the Ticuna and other Indigenous groups. My hosts told me that whites in the area used to hunt Indians for sport.

I visited four Ticuna villages to find out what sort of compensation the survivors of the murder victims wanted. They told me they needed motors for their canoes, so they could shorten the six-hour trip rowing downriver to the local social-security office, and construction materials for houses, so they could live independently and not be beholden to their in-laws. Amnesty groups in several countries provided about $7,000 relief to the massacre survivors.

I’ve never forgotten the kindness and hospitality of the Indigenous people I met, contrasted with the murderous hostility of the white population. Unlike Pereira, I was lucky enough not to experience the latter.

Bruno Pereira was not unique in his courage, determination and dedication, but he is a heroic exemplar for the “next generation of sertanistas” and their allies, brave people like Dom Phillips, who persist in working against deadly odds for social justice in the Amazon and beyond.

Linda Rabben is an associate research professor of anthropology at the University of Maryland.

This essay is based on an obituary of Bruno Pereira published in The Guardian on July 6, 2022.

Cart

Search