An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Silenced Voices:

Silenced Voices: Difficult Belgian-Congolese Heritage and the Iyonda Leprosy Settlement

By Kristina Katherine Garrity and Mick Feyaerts

Student Submission for the Journal of Applied Anthropology

Introduction: Iyonda Then and Now

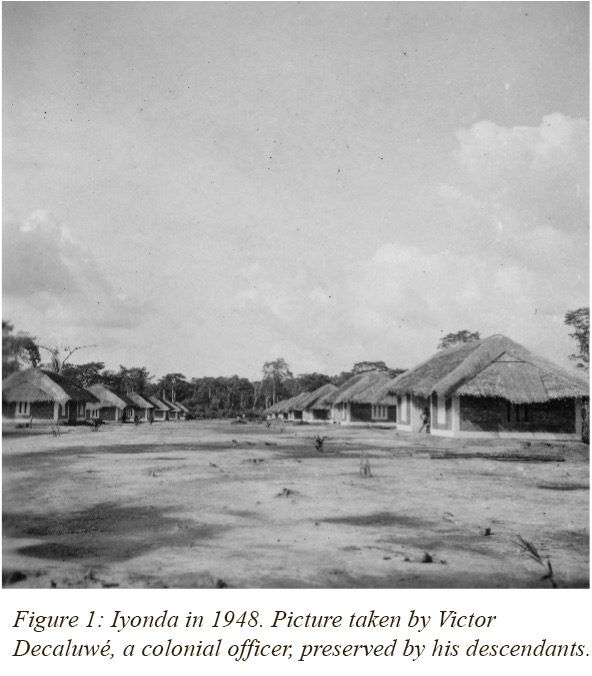

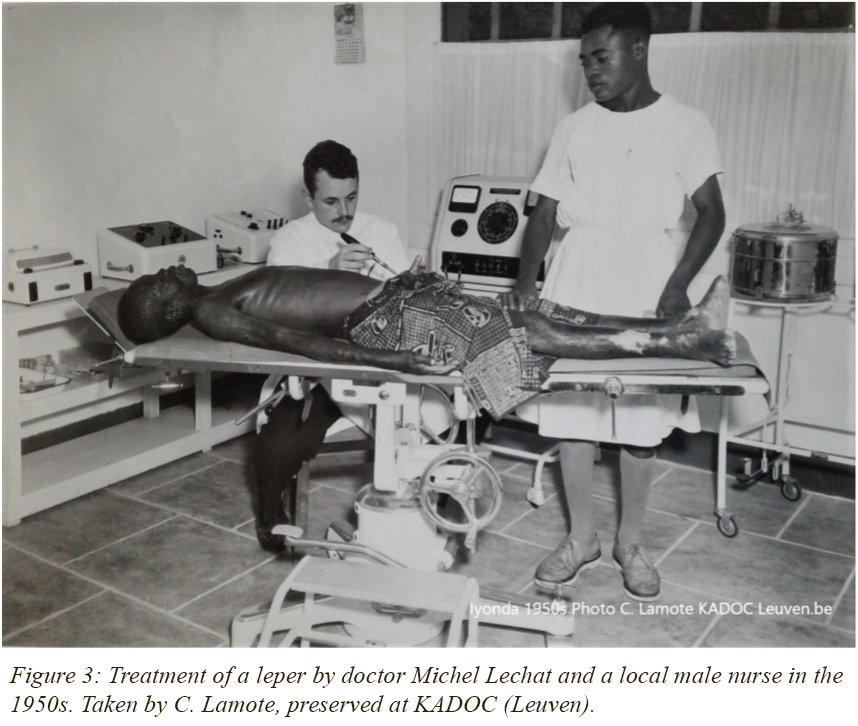

Initially founded in the 1920s by the Soeurs de Notre Dame de Namur (Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Namur), the Iyonda-Mbandaka leprosarium would become the pride and joy of the Belgian colonial medical establishment in the postwar era. By 1957, Iyonda—located in the Equatorial province of the former Belgian Congo, known today as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)—came to host almost 1300 lepers[1] annually. Its remarkable growth has been credited in large part to the leadership of Dr. Michel Lechat, who arrived at the settlement in 1953 as the first permanent medical doctor and leprosy specialist. With the financial support of Aide Médical aux Missions (AMM) and Fonds Reine Elisabeth pour l’Assistance Médicale aux Indigènes du Congo Belge (FOREAMI), Iyonda transformed into a site of cutting-edge treatment for Hansen’s disease under Lechat’s supervision. Its successful curing of hundreds of lepers served as a testament to the power of modern medicine and the rapid construction of European-style infrastructure throughout the 1950s, a reflection of the benefits of the Belgian colonial enterprise at large. Nowhere did the special status granted to Iyonda emerge more clearly than in the decision of AMM to display a maquette of the settlement at the World Exhibition of 1958 in Brussels.

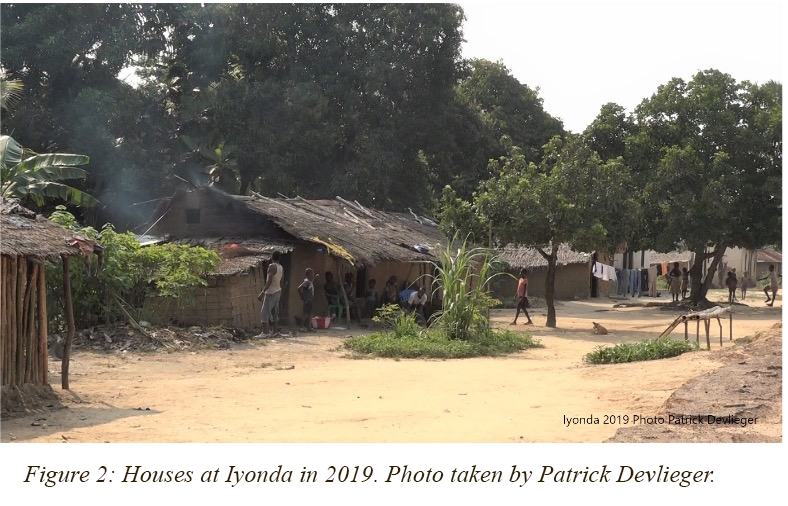

Yet in 2021, the picture could not be more different. Today, the Congolese Sisters running Iyonda struggle to meet the basic needs of the settlement’s current inhabitants, who consist primarily of relatives of former lepers. Residents complain of a lack of professional training opportunities and educational access, which they fear will only exacerbate their marginalization. While the structures built during the colonial era remain, the aura of optimism that once surrounded the settlement in the final days of Belgium’s occupation of the Congo has faded. Where it once occupied a leading position in the long march of progress, Iyonda now appears to exist outside the twentieth century’s grand narrative of progress. The current state of affairs begs the obvious question: what happened? The first phase of the Iyonda@Labs research project at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Flanders focused on finding an answer. Organized by anthropology professor Patrick Devlieger, members of the project’s interdisciplinary team conducted ethnographic interviews and dove deeply into Belgian archives in an effort to reconstruct Iyonda’s transition from a model leprosarium to a space struggling to get by.

Yet in 2021, the picture could not be more different. Today, the Congolese Sisters running Iyonda struggle to meet the basic needs of the settlement’s current inhabitants, who consist primarily of relatives of former lepers. Residents complain of a lack of professional training opportunities and educational access, which they fear will only exacerbate their marginalization. While the structures built during the colonial era remain, the aura of optimism that once surrounded the settlement in the final days of Belgium’s occupation of the Congo has faded. Where it once occupied a leading position in the long march of progress, Iyonda now appears to exist outside the twentieth century’s grand narrative of progress. The current state of affairs begs the obvious question: what happened? The first phase of the Iyonda@Labs research project at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Flanders focused on finding an answer. Organized by anthropology professor Patrick Devlieger, members of the project’s interdisciplinary team conducted ethnographic interviews and dove deeply into Belgian archives in an effort to reconstruct Iyonda’s transition from a model leprosarium to a space struggling to get by.

At the same time as the focus of Iyonda@Labs remains restricted to a single site, an awareness of the larger forces that contributed to Iyonda’s demise remains at its heart. For this reason, this paper not only offers a brief summary of the history that the first phase has uncovered but also links the significance of Iyonda’s history to the decolonization movement currently afoot both within and without the academy. At the intersection between history and activism, this paper argues, the potential power of applying anthropological knowledge to help to right historic wrongs becomes most clear.

At the same time as the focus of Iyonda@Labs remains restricted to a single site, an awareness of the larger forces that contributed to Iyonda’s demise remains at its heart. For this reason, this paper not only offers a brief summary of the history that the first phase has uncovered but also links the significance of Iyonda’s history to the decolonization movement currently afoot both within and without the academy. At the intersection between history and activism, this paper argues, the potential power of applying anthropological knowledge to help to right historic wrongs becomes most clear.

A Slow Exile from History

As ethnographic interviews with former missionaries and archival research at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and KUL’s KADOC depository reveal, Iyonda’s process of abandonment was gradual, beginning with the Congolese Independence in 1960. First, the move towards decolonization precipitated a drastic change in the involvement of FOREAMI and AMM in the region. FOREAMI, for example, became an organization overseen by the new Congolese government. Financial troubles in 1962 marked the end of its operation. AMM, which was reconfigured as Aide Médicale à l’Afrique Centrale, slowly phased out its involvement with Iyonda by the 1970s. In the absence of the consistent subsidies that these two organizations had once supplied, the growth of the settlement slowed. Although three more buildings were constructed following Independence—a school for local children in 1963, a maternity ward and a brewery for lemonade and mineral water in 1972—these were the exception rather than the rule.

The Independence also led to radical transformations in the configuration of Iyonda’s personnel. Indeed, the formal end to Belgian rule over the Congo meant the removal of a permanent position for a medical doctor, whose salary had hitherto been paid by AMM. Until the Zairean government selected a Congolese doctor to take over the post in 1968, inhabitants would be treated by someone who visited the village once a week. Independence also had significant implications for the make-up of Iyonda’s Catholic missionaries. While the Belgian Sisters who supported the settlement remained present a little longer, their ultimate departure left Iyonda’s management entirely to their Congolese counterparts. Without the robust staff that had been subsidized by the colonial government, the medical training, apprenticeships and educational services for which Iyonda had become famous reduced drastically in scope or, as in the case of training for nurses, began to take place elsewhere.

Although documentation in the Belgian archives on Iyonda during the post-Independence era is highly limited, interviews with former Belgian and current Congolese inhabitants of Iyonda indicate that, in spite of these limitations, the settlement has continued to function as an important source of support for almost a century. The construction of the lemonade and mineral water brewery and the purchase of cattle in 1972 opened up new streams of revenue for the village, allowing it to remain in operation. In the early 1980s, ambulatory care for lepers was developed. By 1987, a Catholic mission two kilometers away from Iyonda had become the primary provider of social services within the village, repurposing certain buildings at the colonial settlement for the training of new Sisters. By 1994, over 100 patients were treated daily by a team of three—one Sister, a nurse and a nurse’s aid. Rwandan patients began receiving treatment at the site in 1997. Given the lack of resources medical providers at Iyonda faced, lepers were no longer formally registered at the site by 2003, treated only through ambulatory care with medications. In comparison to the Iyonda of the colonial era, today’s Iyonda offers a fraction of the care it could once provide.

Although documentation in the Belgian archives on Iyonda during the post-Independence era is highly limited, interviews with former Belgian and current Congolese inhabitants of Iyonda indicate that, in spite of these limitations, the settlement has continued to function as an important source of support for almost a century. The construction of the lemonade and mineral water brewery and the purchase of cattle in 1972 opened up new streams of revenue for the village, allowing it to remain in operation. In the early 1980s, ambulatory care for lepers was developed. By 1987, a Catholic mission two kilometers away from Iyonda had become the primary provider of social services within the village, repurposing certain buildings at the colonial settlement for the training of new Sisters. By 1994, over 100 patients were treated daily by a team of three—one Sister, a nurse and a nurse’s aid. Rwandan patients began receiving treatment at the site in 1997. Given the lack of resources medical providers at Iyonda faced, lepers were no longer formally registered at the site by 2003, treated only through ambulatory care with medications. In comparison to the Iyonda of the colonial era, today’s Iyonda offers a fraction of the care it could once provide.

From Recognition to Restitution

At the same time as Iyonda@Labs celebrates the massive effort involved in maintaining Iyonda in the sixty years following the end of Belgium’s colonial regime, it sees the severity of the obstacles described above as the byproduct of a long legacy of colonial oppression in the Belgian Congo. Especially given its special status within the colonial medical establishment and the contribution that research conducted at Iyonda made to scientific knowledge of leprosy, the current state of affairs in the settlement is but another reminder that the injustices embedded in shared Belgian-Congolese heritage have yet to be fully addressed. In this regard, important thematic connections emerge between the recent revival of the global Black Lives Matter movement, the desecration of statues of Belgian monarch King Leopold II and the overarching aims of the Iyonda@Labs project itself.

First, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police officer Derek Chauvin, which was videotaped and circulated through countless social media platforms in the summer of 2020, reignited the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Founded in response to the acquittal of the murderer of Trayvon Martin, a black teenager who was shot by a neighborhood vigilante in 2013, BLM’s primary goal is to dismantle systems of white supremacy that routinely deny Black people’s humanity and render them targets of violence. Although BLM was initially founded in the US, the spread of chapters across the globe bears witness to the reality that racism and white supremacy are not America’s problems alone. Instead, important commonalities have emerged between the ongoing conversation about racial equity in the U.S. and recent confrontations with the weight of colonial brutality in Europe.

In Belgium, this confrontation has taken the form of demands for more honest recognition of the state-sanctioned violence perpetrated against the Congolese people. In early June 2020, shortly after the murder of George Floyd set off protests across America and pleas for the removal of Confederate statues, thousands of Belgians also took to the streets articulating similar demands for the statues of King Leopold II, who initiated the Belgian colonization of the Congo in 1885. Even within Europe, King Leopold II’s rule is infamous for being especially cruel, resulting in the death of an estimated half of the Congolese population at the time. Reliant upon forced labor to fuel its trade of rubber, ivory and minerals, the Belgian colonial authorities used the amputation and mutilation of limbs as a common means of punishment when Congolese villages failed to meet the quotas they imposed. In a symbolic act protesting the silence that has historically shrouded this legacy, protestors across the country have defaced public statues of King Leopold II. Some chose to paint his hands blood red, while others have covered the statues with graffiti condemning the former monarch as a racist. In this way, the resurgence of global awareness of racism has bolstered the long-standing struggle to fully reckon with Belgium’s bloody colonial past.

Fortunately, the activism of the past year has succeeded in shifting the ongoing debate over difficult Belgian-Congolese heritage. In a historically unprecedented gesture, the current Belgian king wrote a letter to the DRC’s President Felix Tshisekedi on its 60th anniversary last summer, acknowledging the violence and cruelty committed during Belgium’s colonization of the region. Such a letter becomes all the more remarkable considering that King Leopold II has been defended, and in some instances even praised as a hero, by various public figures in the past few years. Although the struggle to come to a clear consensus about Belgium’s violent past will likely continue—schools in Wallonia, the French-speaking region of Belgium, have only recently begun to revise their history curricula—this shift has opened up space for new discussions about reparations between Belgium and the DRC. Given the enormity of the damage wrought during the colonial period, such reparations will need to take multiple forms. One might include the return of stolen Congolese art from to the DRC; another could involve financial compensation to the former colony, as Germany has recently done through its $1.3 billion payment to Namibia as redress for its genocide of the Herero and Nama people. Countless possibilities abound.

It is in this new spirit of restitution that Iyonda@Labss hopes to make a contribution. Where a thorough investigation of all archival material on Iyonda was the focus of the first phase of this project, the second phase is about taking the information gathered and bringing it to Iyonda’s current inhabitants. At the time of this paper’s writing, several team members are at Iyonda, sharing compelling material, such as photos of the settlement during the colonial era and images of former patients, with the current residents. By moving this documentation beyond the confines of the Belgian archives, the project aims to empower those who live at Iyonda, including the Catholic Sisters who keep the site running, to make this history their own. The historic marginalization of the voices of the lepers and female missionaries makes their ownership of the past all the more critical. At the close of the team’s visit, they will put up an exhibition that synthesizes their mutual exploration of Iyonda’s rich heritage. Such an exhibition, Iyonda@Labs team members hope, is but the beginning of many collaborative initiatives that will break the silence left in colonization’s wake.

Conclusion: Filling the Gaps

One such initiative involves the elaboration of the database created during the first phase of the project. To contextualize, the bulk of the research conducted by the authors of this paper involved combing through all of the archives for any relevant material they might contain on Iyonda. All materials were photographed, uploaded to a shared Team Google Drive and then linked to a database, where they were then classified by research direction. These research directions included: institutional politics in the Belgian Congo; construction of the colonial regime; the Belgian public’s perception of the Congo; everyday life in Iyonda; and gaps in the archives/hidden voices. Drawing upon their prior training in history—Feyaerts wrote her history master’s dissertation on Jesuit missionary periodicals and Garrity majored in intellectual history as an undergraduate—the two research assistants then analyzed the digitized material in relation to their relevant theme.

As the research direction of hidden voices suggests, Feyaerts and Garrity approached the archives critically, attempting to read against their grain. Indeed, the researchers’ work in archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the university’s Documentation and Research Centre of Religion, Culture and Society (KADOC) pointed to the role that the genesis of written material played in the legitimation of the colonial regime. The sheer volume of information preserved, with several documents reappearing multiple times in one or both of these major archives, illustrated this most clearly. Because of their prior exposure to archival work, Feyaerts and Garrity could recognize that the emphasis on the voices of colonial administrators and doctors produced by this repetition meant the drowning out of others. As a result, they paid special attention to the way in which the discourse surrounding Iyonda, which was constructed not only through text but through image as well, left critical perspectives out. Most obvious was the elision of the voices of the missionaries who initially founded Iyonda, of the Congolese personnel who played an integral role in the provision of medical care and of the lepers who spent many years receiving treatment at the settlement.

While the bias towards the perspective of the Belgian colonial administrators is likely the product of the types of archives that were accessible during the first phase of Iyonda@Labs, there nevertheless remains a marked lack of recognition and clarity surrounding the role that the Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Namur played in the genesis of the settlement. For example, other sources credit Father Van Goethem, the Vicar Apostolic of Coquilhatville, with inspiring a group of sisters from the congregation of the Filles de Notre-Dame du Sacre-Coeur (Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart) to start the settlement in 1945. The archival clarity of the involvement of the male-dominated colonial establishment in Iyonda draws a sharp contrast with the ambiguity of the role played by the female Catholic sisters. In no documentation found thus far have these sisters—neither Belgian nor Congolese—been able to speak for themselves in any meaningful way. Similarly, although the archives contain images of and statistics counting Congolese medical personnel and lepers currently receiving treatment, they are left nameless. Given the broader context of colonial atrocity in which Iyonda emerged, this anonymity and silence must be taken seriously.

Recently, Iyonda@Labs has requested access to the archives of the archdiocese in Mbandaka, which holds important pieces from when Iyonda was run primarily by Catholic missionaries. These documents were kept at Iyonda but relocated to the archdiocese after repeated lootings. The ambition is to add these materials to the database so that a more chorus of voices can emerge. The chancellor’s decision on whether or not the materials are accessible to the project should follow soon.

By facilitating a more balanced and accurate representation of Iyonda’s past, the database aims to help. Yet this project was never intended to only be historical: video footage of Devlieger’s 2019 visit to Iyonda, along with recent interviews with former Flemish colonials and missionaries, also form an important component of the database. In this regard, Iyonda@Labss represents an example of how history and anthropology can come together, with the anthropological awareness of the current circumstances of the leprosy settlement and its connections to broader systems of global injustice guiding its approach to Iyonda’s past.

[1] We will consistently use the term ‘leper(s)’ (lépreux in French, leproos/leprozen in Dutch) as a reflection on of the term being used in archives and during interviews.

Cart

Search