An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

Interview with Anthony Oliver-Smith

Disaster Research, Displacement and Climate Change: Society for Applied Anthropology Oral History Project Interview with Anthony Oliver-Smith

Disaster Research, Displacement and Climate Change: Society for Applied Anthropology Oral History Project Interview with Anthony Oliver-Smith

Tony Oliver-Smith’s career spans the important developments in disaster research and human displacement and depicts these topic’s expansion from the margins of social research to a robust multidisciplinary sphere of inquiry. Various themes are discussed in the text including vulnerability to disaster, adaptation, and global climate change. Oliver-Smith was the winner of the Society’s Bronislaw Malinowski Award. He is now Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Florida and maintains his career in research and consulting. The interview as done by Gregory Button also an accomplished disaster researcher. The transcript was authenticated and edited by John van Willigen.

BUTTON: It's Saturday, February 2nd, 2011. This is Gregory Button talking with Tony Oliver-Smith, about his long and distinguished career in anthropology, in particular, disaster studies and that would also include displacement. Largely, development-oriented displacement issues. Tony, why don’t we start by talking a little bit about your early entry into anthropology. Where did you go to school as an undergraduate?

OLIVER-SMITH: Okay. I went to Brown University as an undergraduate. And I was a Spanish major. My first connection to anthropology was I became really interested in the Hispanic world. I set out as a project to learn Spanish [and] hadn't heard of anthropology per se or anything like that. I got to Brown and majored in Spanish, Spanish literature, spent a couple of summers in Spain, working in a Spanish student work camps. They were--they were kind of small projects in villages. It was kind of a pre‑Peace-Corps. Or it was maybe even parallel to the Peace Corps at that time. Because it was the beginning years of the Kennedy administration. And I basically dedicated myself to learning Spanish. I took a course--one course in anthropology, from Dwight Heath, who was an Andeanist anthropologist, largely specializing in alcohol studies in Bolivia. And I enjoyed it but it didn't really grab me one way or another. I just basically enjoyed the course. But as I say my focus was really on absorbing as much information and perspective and culture in the Hispanic world. And so, after graduating, I decided--I got a job in Peru. I got a job as a locally hired employee of the Peruvian North American Cultural Institute, in Lima and, spent about a year working there teaching English and assisting the Director of Student Activities. And I didn't really care that much for the job, but I just became fascinated with Peru. And I had this idea, that I would probably go into the Foreign Service. And I had a number of fairly hilarious mishaps regarding the embassy and foreign or international affairs between Peru and the United States, that convinced me that I probably was not cut out to be in the Foreign Service. Actually, failing the Foreign Service exam by three points was probably the best thing that ever happened to me. Anyway, I decided I'd go back to graduate school. And, I had Paul Doughty and James Scobie, who were two professors at Indiana University had come down--and I had met them, because Indiana University had a junior year abroad program in Lima. And so I interviewed with them. And I was accepted to IU and went back, to get an MA in Latin American studies--again, not with any idea about anthropology. The first course I signed up for-- I walked in, day one, to Paul Doughty's class on indigenous peoples of Latin America. And I thought, okay this is really what I'm really interested in. And so I continued on in Latin American studies and I got a summer research grant--went down to Peru. It was called the Cornell-Harvard-Indiana-Illinois something or other, Field School. And Paul Doughty was the director of that field school. And we went down to the Callejón de Huaylas, which is this valley in the north-central Andes, about 450, 470 kilometers north of Lima. And I did a study of folklore. In some of my trips into the Andes, during the year I spent in Lima people would sometimes look at me and say, "Pishtaco." And pishtaco is a monster. And so I thought, well, -it'll be fun to explore what this is all about. And so that was my project. The valley is such an incredible place that I decided I wanted to do my dissertation research there. And so what happened was I just--I then became very interested in political economy, economic anthropology. And I wanted to study the market. And so after passing my quals, in 1969 I was all set to go to-- I got funded--I got two grants, a Fulbright and a Midwestern Universities Consortium grant and was all set to go to Peru, in the fall of 1969, to study the market, in this town called Yungay, but a series of family issues and difficulties came up and I decided I'd postpone for a year. And so I would have been there from September of '69 to September of 1970. I postponed for a year, went back home, to New England, got a job in Boston, working as a civil rights investigator for the state of Massachusetts really interesting job, and, might have actually been a career track. There was a moment when I thought, I'm going to stick with civil rights. But I figured that I had really invested four years of work in a MA and all my coursework and quals for the PhD. So I intended to go to Peru to do my dissertation research in September of '70. Well, in May of 1970--a huge disaster, May 31st, 1970, 3:23 in the afternoon. An enormous area in north-central Peru--there was an earthquake, 7.7 on the Richter Scale, that absolutely devastated, over a period of forty seconds an area about the size of Belgium, Holland, and Denmark combined, three small European countries--absolutely flattened--on the coast and the mountain regions, of the Departments of Lima and the Departments of Ancash and extending even somewhat north to the Department of La Libertad. And one of the central tragedies of that event was that the earthquake shook loose a piece of the tallest mountain in the Andes, in Peru, Mount Huascarán, this 22,000-plus-feet high. And this large chunk of ice dropped a vertical mile. Because the face of Huascarán was concave. And so this piece broke off the top of the mountain, dropped a vertical mile, hit another glacier, and quadrupled in size. And this mass went rocketing down the hills and jumped a protective hill and obliterated the town of Yungay, just buried it--but not only buried it but ground it up. Because the mass of mud and rock and ice was going somewhere in the neighborhood of 200 miles an hour. It killed probably 90% to 95% of the people in the town. And so we found out about it about four days later, on June third. And I thought, My God if these family issues had not happened, I'd have been there.

BUTTON: -and you wouldn't be here right now.

OLIVER-SMITH: I wouldn't be here right now. Exactly--. So what happened was that I thought, well, okay, I'm going to have to take my economic anthropology study, my market study, and go somewhere else in Peru. Well, Paul, in the meantime--because he had worked in the valley too-had already taken off and gone down to work in relief, in whatever way he could. And one of the things that he did, along with a guy from USAID, was to set up something called the Peru Earthquake Relief Committee. And it was composed of ex‑Peace-Corps-volunteers, anthropologists, and other professionals who had worked in the region. And they got a small grant. They raised money. They raised if I recall, it was about $100,000, which is a lot of money in 1970 for small projects. And so he was down there. And then he came back. And I met with him. I flew out from Boston, flew out to Indiana. And I said, "Well, I guess I'm going to have to go the Mantaro Valley or down to Cusco." And he said, "No"----uh, "Go back down to the Callejón. Go to--go to the valley, and study what's going on there. Because no anthropologist has ever studied there." Well, what I subsequently found out was that nobody had done any research, in the nonindustrial and industrialized world, on disasters. Well, that's not entirely true. None in Latin America. When he convinced me to go back down-- And I was--I was kind of nervous about this. I mean, it was going into the field with absolutely no knowledge of what you were going to study. I had about two weeks to read everything I could put my hands on about disasters in the developing world. And it turned out that there was almost nothing. Disaster research was dominated by sociology and geography. And it was mostly oriented--well, it was mostly about individual and organizational behavior in the developed world, that is, Europe and North America. A lot of stuff on police departments, fire departments, emergent groups, All perfectly respectable research but pretty first-world focused--and nothing on Latin America. And so, basically, as I say, I had time on my hands. I found that some anthropologists had actually done some disaster research. But it was mostly in the Pacific. David Aberle had an article in Human Organization, on typhoons in Yap. Eric Schwimmer had studied a volcanic eruption in Papua New Guinea. Raymond Firth had studied and has a chapter, ‑ in Social Change in Tikopia, on a famine. The most relevant and probably the most important, and still important, research was done by Anthony F.C. Wallace. He did some studies for the National Research Council in Worcester, Massachusetts, on a tornado. And it's there that he developed his spatiotemporal matrix for studying a disaster. In other words, he broke the disaster into temporal periods and spatial domains, in the sense of the smallest circle, at the beginning, at the center of the set of concentric circles is the impact zone. And then he moves outwards to the various zones and their relationship to the impact. And by the same token, he has this model, on time, that is pre‑disaster, warning, alert, impact, immediate post-disaster, recovery, reconstruction, et cetera, et cetera. And people still use this. And in that sense, Anthony F.C. Wallace is really the pioneer that I look to. So that's what I was able to look at. But, I mean, we're not talking about more than a dozen articles. So I took off to Peru—and went down and, uh, took a bus up to the--up to the valley and began a very, very unformed dissertation research project. I sort of sketched out, for my donors or my funders, rather, what I planned to do.

BUTTON: Were the donors the Peruvian relief committee?

OLIVER-SMITH: No, no, no. The funders, at that time, were the Midwestern Universities Consortium for International Activities.

BUTTON: Okay.

OLIVER-SMITH: And I also got a Fulbright. And I didn't know that I could postpone the Fulbright. I could have had two years of funding. I said, "I'll take the Midwestern Universities Consortium grant," because it was slightly larger. And I began this study, just basically, I hit the ground running, as they say. I knew the area. I had lived in Yungay before the disaster.

BUTTON: At that point in time, how long had you lived in Yungay before you had to return? What degree of familiarity did you have with the community?--

OLIVER-SMITH: In 1966, I spent three months there--

BUTTON: --okay--

OLIVER-SMITH: --in the summer field school, and met people, and had a great time. Basically, I was doing fieldwork on that folklore issue. And that's when I determined that I wanted to go back and study there. And the market in Yungay was really a neat place. And so I went back to Yungay. I had some friends there who had survived, actually, miraculously survived. One of them had a tent. And he allowed me to live in the tent for a while. He lived in the back. He had a pickup truck with a cabin on the back. He slept there. His mother slept under kind of a lean‑to, made out of roofing, corrugated roofing material. And he had a tent, that had come in with all the aid, and let me spend--I was there about, oh, ten days. And then I moved over to Yungay, to the camp. Now, what had happened was that the avalanche had come down, obliterated the town. The survivors, those who had, through luck, not been in town that day. A friend of mine decided he was going to go have a beer with some friends in another town. Another person, his whole family survived because, the day before the disaster, his wife was very pregnant. And she had gone out to visit her parents, in the countryside, outside of the town. And her labor pains started out there, so she had her baby out in the countryside. Sunday morning, Manuel packed up the rest of the kids--there were seven other kids--took 'em all out to the countryside, to see the new baby. So that's how they survived, the roughly 300 to 500. It was hard to really get an accurate count, because by the time I'd gotten there, some people left, and other people had come back and that kind of thing. But his whole family survived. And so the survivors moved about half a kilometer, maybe 700 meters north of the avalanche. And there they built lean‑tos and began caring for the wounded [providing] that initial aid. We know that the first-responders to disasters are always the survivors themselves. And because the avalanche and the earthquake threw up so much dust, nobody knew what had happened to Yungay. Nobody knew that it had been buried because all communication was cut off. All the roads leading up to the valley the earthquake had simply shaken them off the side of the mountain. So the valley was, for all intents and purposes, pretty isolated for a long time. And it was four days before they realized what had happened to Yungay. This town of 4,500 people had simply disappeared. And so, when I arrived, it was about three months later. I'd had a contract, that is, -an employment contract with the state, the antidiscrimination agency. So I would work for a year, September to September. So in September, I went to Peru. And then I went up to the valley. This was when the encampment, just north of the avalanche, was in a place called Pashul Pampa. Pashul is a kind of fruit. And pampa means field. They had set up a camp of lean‑tos there. And then eventually, when the aid started to come in, it was in the form of tents and food and that kind of thing, medical care, to some degree. And so, when I arrived, everybody was in tents. And they gave me a tent. So I moved over from my friend's house, and the tent had lent to me and I got my own tent there. And I started, basically, doing research. And when the temporary barracks housing came in, I moved into one of those. And I spent fifteen months working in--and doing fundamentally an ethnography of recovery. My dissertation eventually took on the form of a study in social change after disaster. But when I was actually doing the research, I was just trying to record everything that was transpiring in that village in a sense, in that camp, of how people go about reconstructing their lives after what is essentially almost total obliteration. So I studied the political changes, the economic changes, how the economy re‑reconstituted itself, how the authority structure reestablished itself, how rural-urban relations, which really, in that area of Peru, means indigenous-national population relations, cultural life, the whole process of grief and mourning, and largely, the politics of recovery too, the conflicts with the aid agencies, which I found eventually, when I went back and began doing more reading, in the sociology of disasters, again, mostly the first-world, is not an uncommon phenomenon. Disaster victims very often end up in conflict with those who are in charge of recovery.

BUTTON: Then and now.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yes, then and now. And that's one of the things that I think is really quite extraordinary. We've seen this year of extraordinary disasters and some of them, in effect, are replicating problems I saw forty years ago.

BUTTON: A much larger scale, in the case of Haiti but the same common denominator.

OLIVER-SMITH: On a much larger scale.

BUTTON: Yeah.

OLIVER-SMITH: So, this is how, I spent fourteen months. I also did a little applied work.

BUTTON: What do you mean by applied here? Were you working for other people?

OLIVER-SMITH: Remember I was studying the process but, at the same time, I also was working with in a very minor way, with the Peru Earthquake Relief Committee, the thing that Paul Doughty and Brian Buhn had founded.

BUTTON: Were the members of the committee outsiders or was it a mixture of people who lived in Peru and also were North Americans and other people?

OLIVER-SMITH: They were North Americans and other people who had worked in the Callejón.

BUTTON: Okay.

OLIVER-SMITH: Anthropologists. And the perspective that Paul brought to this, and to Brian Buhn, this USAID official, who had a lot of experience in Peru, was that these big projects were going to miss a lot of small communities. Because a lot of these communities didn't have roads. They were indigenous. And so what they thought if they could get the small funding, the small, amount of money and fund really small, local-level projects that would do immediate good. And because we--and I say we because we were all people who had lived and worked there knew the problems of these communities in a general sense, we thought that we could provide really crucial, low-level forms of aid, that would really help them in their recovery. So we started. The earthquake affected a huge area, not just the avalanche. So villages were reduced to rubble, all over the Callejón. Well, for villages that didn't have roads, one of the first problems after you've, really gotten past the initial emergency period is that you're surrounded by rubble. How do you clear rubble? Well, you know, we clear rubble with bulldozers and dump trucks. Well, in a village that has no road, how do they clear all that adobe? Well, we thought, wheelbarrows. So we purchased wheelbarrows and put 'em on the backs of mules. And they went up to communities. And the communities had wheelbarrows and they could take the busted-up adobe and dump in the quebrada, dump it in the canyon, and then clear the rubble, so that they could start rebuilding. We funded cement to repair irrigation canals, that had been shaken off the sides of mountains, we funded daycare centers for market women, stuff like that, you know, really low-level but very precisely that would allow people to do certain kinds of absolutely necessary things they needed to get back on their feet, like clear rubble, like getting water to their crops, like allowing the women to go back [to market]--and women are the marketers in Peru to go back to work. So that was that kind of work that those were the kinds of projects that we funded. So I was doing a little bit of that, at the same time. I spent that year trying to document everything that was going on in that community. Because, again, it was not a really focused project. I didn't have time to really do what we do now, which was, you know, ‑

OLIVER-SMITH: Anthropologists. And the perspective that Paul brought to this, and to Brian Buhn, this USAID official, who had a lot of experience in Peru, was that these big projects were going to miss a lot of small communities. Because a lot of these communities didn't have roads. They were indigenous. And so what they thought if they could get the small funding, the small, amount of money and fund really small, local-level projects that would do immediate good. And because we--and I say we because we were all people who had lived and worked there knew the problems of these communities in a general sense, we thought that we could provide really crucial, low-level forms of aid, that would really help them in their recovery. So we started. The earthquake affected a huge area, not just the avalanche. So villages were reduced to rubble, all over the Callejón. Well, for villages that didn't have roads, one of the first problems after you've, really gotten past the initial emergency period is that you're surrounded by rubble. How do you clear rubble? Well, you know, we clear rubble with bulldozers and dump trucks. Well, in a village that has no road, how do they clear all that adobe? Well, we thought, wheelbarrows. So we purchased wheelbarrows and put 'em on the backs of mules. And they went up to communities. And the communities had wheelbarrows and they could take the busted-up adobe and dump in the quebrada, dump it in the canyon, and then clear the rubble, so that they could start rebuilding. We funded cement to repair irrigation canals, that had been shaken off the sides of mountains, we funded daycare centers for market women, stuff like that, you know, really low-level but very precisely that would allow people to do certain kinds of absolutely necessary things they needed to get back on their feet, like clear rubble, like getting water to their crops, like allowing the women to go back [to market]--and women are the marketers in Peru to go back to work. So that was that kind of work that those were the kinds of projects that we funded. So I was doing a little bit of that, at the same time. I spent that year trying to document everything that was going on in that community. Because, again, it was not a really focused project. I didn't have time to really do what we do now, which was, you know, ‑

BUTTON: --create a research design and--

OLIVER-SMITH: -- students put together, it's a three‑ to four-month process--

BUTTON: --right--

OLIVER-SMITH: --in which they develop a theoretical framework and come up with a research plan and research design, instruments, and all of this, kind of very, very, methodical--

BUTTON: Even to this day, those of us who work in disasters have to enter the field with that same kind of inductive process. We hit the ground, try to figure what's going on. We don't have the liberty or the opportunity to create a research design that [is] traditional.

OLIVER-SMITH: That's essentially true. What we do have now, though, is roughly forty years of research--

BUTTON: --right--

OLIVER-SMITH: --to call upon. I really didn't have much. So I was kind of making it up as I went along. So that was the beginning of this research project, that eventually lasted ten years. Not ten consecutive years but, the first field trip was about fourteen months. And then I went back for a couple of months in 1970 to the end of seventy-one. Then again in '74, '75, and then 1980.

BUTTON: So did you complete your dissertation research and write it, after the end of the first fieldtrip?

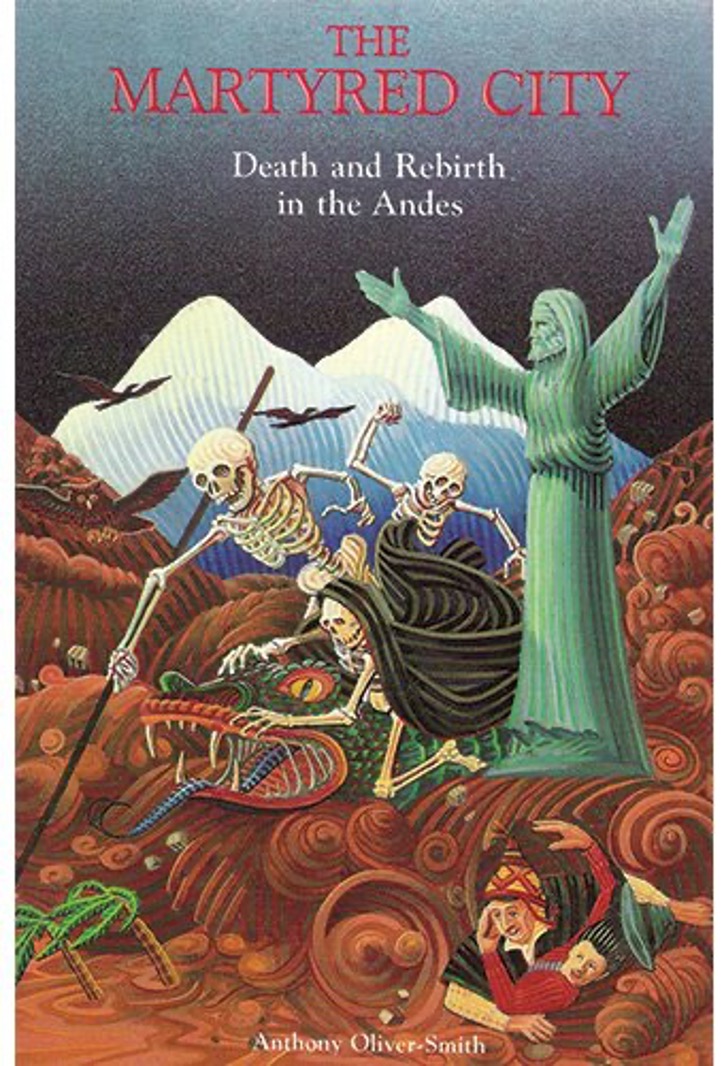

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah. The dissertation is really about that first year, that is, going from absolute, total destruction to the beginnings of the formation--and the struggle to actually to build a new town, to re‑found the town. And they were--by that time, they were calling themselves Yungay Norte, North Yungay. And eventually, it would become Yungay again. The government said to them, "Look, you're in geological peril here. We're going to move you about fifteen kilometers to the south." And the people adamantly refused. They said, "No. We will not abandon our dead." That was the way they phrased it. But the reasons that they had for not wanting to move were multiple. They were cultural, they were emotional, they were political, in the sense that they wanted to remain as the capital of the province, and they were economic, because they knew that the area that they occupied would be supported by this large rural population. The area that they were going to be moved to have a much smaller rural population. And they said, "Look," you know, "these towns--" They knew very well that these towns didn't exist without the support of a rural population. When I say support, what I mean is basically, a market-shed, but a market-shed for urban services, not just markets. The church should have been there and, you know, all of this. So this began a resistance movement, to the idea of being again resettled. An aspect of the study was to how they mobilized their resources, locally and also through their migrant community in Lima, to resist what was a military dictatorship--a relatively benign one but, still, a military dictatorship. And they resisted them. They eventually achieved their goal. I talk about this in the book quite a lot, in the book called The Martyred City, which is the book that came out of this study. So this is the way this research undertaking began. Now the really interesting thing, for me, and what has really been interesting to be part of, over the last thirty or forty years, is that, when I went down to Peru to do this research, disasters were really looked in terms of natural forces, natural agents. An earthquake did it. A hurricane did it. A typhoon did it. A volcano did it. And human beings responded to it. So there was organizational and institutional behavior to this disaster. And--well, in some ways in the public media, there was a lot of sort of characterization of disasters as acts of God or accidents of nature. And one of the things that came out of the research that we began to do in the developing world was coming from anthropology but also a lot from geography, cultural geography and not just working in Latin America but working in Africa. Some of them were Americans. Some of them were British. Some were French. The French were working largely on the issue of famine in Africa. And some of them were Americans, as I say, working in both Africa and Latin America. And we began to say, "Well, why are disasters so much worse in the developing world, that you have hurricanes of somewhat similar intensity, earthquakes of similar intensity and you get a couple hundred people dead in the United States or maybe even [less than] that and you get 65,000 people killed in Peru?" So we began to question the idea about "Wait a minute. The earthquake did it." Because the societies--the different societies were showing so many differences in degree of damage. And out of this emerges, the concept of vulnerability.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah. The dissertation is really about that first year, that is, going from absolute, total destruction to the beginnings of the formation--and the struggle to actually to build a new town, to re‑found the town. And they were--by that time, they were calling themselves Yungay Norte, North Yungay. And eventually, it would become Yungay again. The government said to them, "Look, you're in geological peril here. We're going to move you about fifteen kilometers to the south." And the people adamantly refused. They said, "No. We will not abandon our dead." That was the way they phrased it. But the reasons that they had for not wanting to move were multiple. They were cultural, they were emotional, they were political, in the sense that they wanted to remain as the capital of the province, and they were economic, because they knew that the area that they occupied would be supported by this large rural population. The area that they were going to be moved to have a much smaller rural population. And they said, "Look," you know, "these towns--" They knew very well that these towns didn't exist without the support of a rural population. When I say support, what I mean is basically, a market-shed, but a market-shed for urban services, not just markets. The church should have been there and, you know, all of this. So this began a resistance movement, to the idea of being again resettled. An aspect of the study was to how they mobilized their resources, locally and also through their migrant community in Lima, to resist what was a military dictatorship--a relatively benign one but, still, a military dictatorship. And they resisted them. They eventually achieved their goal. I talk about this in the book quite a lot, in the book called The Martyred City, which is the book that came out of this study. So this is the way this research undertaking began. Now the really interesting thing, for me, and what has really been interesting to be part of, over the last thirty or forty years, is that, when I went down to Peru to do this research, disasters were really looked in terms of natural forces, natural agents. An earthquake did it. A hurricane did it. A typhoon did it. A volcano did it. And human beings responded to it. So there was organizational and institutional behavior to this disaster. And--well, in some ways in the public media, there was a lot of sort of characterization of disasters as acts of God or accidents of nature. And one of the things that came out of the research that we began to do in the developing world was coming from anthropology but also a lot from geography, cultural geography and not just working in Latin America but working in Africa. Some of them were Americans. Some of them were British. Some were French. The French were working largely on the issue of famine in Africa. And some of them were Americans, as I say, working in both Africa and Latin America. And we began to say, "Well, why are disasters so much worse in the developing world, that you have hurricanes of somewhat similar intensity, earthquakes of similar intensity and you get a couple hundred people dead in the United States or maybe even [less than] that and you get 65,000 people killed in Peru?" So we began to question the idea about "Wait a minute. The earthquake did it." Because the societies--the different societies were showing so many differences in degree of damage. And out of this emerges, the concept of vulnerability.

BUTTON: Which, to date, hadn't really been developed, as a concept.

OLIVER-SMITH: No! The concept had not been developed at all. Well, actually, Gilbert White, who was a geographer at University of Colorado, talked a little bit about vulnerability. But it was largely in sort of accident.

BUTTON: Very narrow sense.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah, it was very narrow terms. He was talking about occupying floodplains and stuff like that. In the U.S., so again, there was very little mention of the developing world. And so what began to emerge was the fact that, okay, we have societies that, in effect, exhibit different patterns of vulnerability. And why do they exhibit different patterns of vulnerability? Well, if they're all in the developing world, what we have then is something that's coming out of political economy here. And, of course, this was the 1970s. And in the 1960s, you have the whole development of underdevelopment, of dependency theory, of all of this, the radical critique. And so disasters, in effect, become one of the strains in this. But disaster research is not integrated, necessarily, into political economic analysis, which is largely focused on development and, you know, land tenure and unequal terms of trade and things like this--okay? So we're still a little bit on the edges of this because of what we've been finding out, that kind of theorizing, that kind of discussion, now we begin to use it. And we begin to frame things not so much in terms of earthquakes and hurricanes but in terms of disasters as the outcomes of unresolved patterns of development or problems of development, that, in effect, it is the society that turns a natural hazard into a disaster.

BUTTON: --or into a larger disaster.

OLIVER-SMITH: Or into a larger disaster. I mean, there some di‑‑some events that, in effect--

BUTTON: --are catastrophic,

OLIVER-SMITH: --they're going to be disruptive, but if your vulnerability is not extreme, you'll manage it.

BUTTON: Um-hm.

OLIVER-SMITH: The idea of resilience hadn't emerged yet, for us. But at the same time, and this is very interesting--—Buzz [Crawford S.] Holling, in ecology, is writing--at 1974, is writing about--introduces the concept of resilience in ecology. And the same time that Ben [Benjamin] Wisner and Phil O’Keefe are talking about vulnerability and disasters, and then some of us, myself begin to pick it up, in the mid‑ to late seventies and start to write about vulnerability. And so what we have emerging, then, are these parallel theoretical developments. What has really been interesting in Latin America, a whole network of disaster researchers begins to emerge in the late eighties, early nineties. You begin to see a network of really excellent researchers in Latin America, focusing on, basically, understanding the social dimensions or social aspects of disasters. And I became part of that network.

BUTTON: This network, I assume, is a larger network than just anthropologists per se.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yes, it is. It's an entirely multidisciplinary. And it's called the Network of Social Studies and Disaster Prevention in Latin America. And that's a translation. It was started in Peru, by a guy who is now with the UNDP's [United Nations Development Program] disaster, one of the chief disaster officers of UNDP. And it was a group of people, we met at a conference that was organized at the Royal Geographical Society in London on the issues of disasters and development. And I didn't know who else was studying in disasters in Latin America. I thought we were all kind of disjointed. We didn't know the--about the existence of others. So we met, Andrew Maskrey, Allan Lavell, and I and other people. But the three of us working in Latin America met at the Royal Geographical Society and discovered the existence of the others and said, "My God. This is amazing." Because we literally were working in isolation. And we met. And then, about six months later, UCLA had a large conference, that invited a lot of Latin Americans. And we began to connect with Virginia Garcia, from Mexico, Sergio Puente, from Mexico, several other Latin American disasters. And out of that was the nucleus for the formation of this network that has been very influential. But between the European and North American anthropologists and cultural geographers and the Latin American historians, anthropologists, geographers, urban planners, this whole sort of theoretical perspective, that disasters are social events and that their origins are social, that they emerge from society rather than from nature began to gain momentum. And I think the most interesting thing about this whole thing is that, in the twenty-five years between, say, 1975 and 2000, we changed the way people think about disasters in the world. And it's been really fascinating to be part of that--to be part of that movement. We moved from disasters as acts of God or accidents of nature to disasters as being embedded in the social structure of societies the material, the social structure, and the instantiation, to use David Harvey's term, of the social structure and the built environment. And that's been, I think, probably the most interesting and extraordinary aspect of my experience in the field. It has been really interesting to be part of that movement. And what's interesting now is that we see this, the joining of disaster research, now, with the idea of resilience, that comes out of ecology. And this is also, I think, a kind of interesting theoretical moment. But it has to be developed. And there's still a lot to do, I think, with the concept of vulnerability, which has its own problems. Vulnerability has been a very useful term for framing and understanding disasters. But it has a way, if it's not applied correctly, of disempowering people.

BUTTON: --and blaming the victims.

OLIVER-SMITH: To some degree. Well, you can say blaming the victim. But very often, the people, in effect, are the victims of unequal relations of power, and in their own circumstances. And by the same token, underdevelopment is not something‑‑and this comes out of the 1960s and ‑70s dependency theory--underdevelopment is not something that is homegrown. It's the outcome of both internal and external relations. And, so what we see, then, is that disasters move way out of sort of organizational and behavioral sociology into political economy and political ecology.

BUTTON: And particularly within anthropology and geography.

OLIVER-SMITH: Particularly within anthropology and geography. But sociologists are doing that now.

BUTTON: --yeah. But somewhat more late than--(laughs)--

OLIVER-SMITH: --yeah, a little bit later than--

BUTTON: -- little bit later.

OLIVER-SMITH: And there's still quite a difference in what I would call the acuity of the studies. There is a distinctly political economic and political ecological framing in culture‑‑in geography and anthropology. It's a bit less so in sociology. But I find it very hard to characterize one field as opposed to another. Because there are individuals in all three fields.

BUTTON: And such mutual influence between the fields in the last two decades, that-- OLIVER-SMITH: --a lot of influence.

BUTTON: --there's probably as much difference within any sector as there is between the different subfields.

OLIVER-SMITH: --yeah, that's a good way of putting it. The thing that I think is really important is that, basically, disasters became a lens for examining and for critiquing society, as opposed to simply something that happened to a society and so we study how it responds. We went [to] the vulnerability perspective, that whole risk and vulnerability perspective, in a sense, becomes now not so much just studying what happens but explaining why it happens. And that, I think, has been an enormous breakthrough. Now, the big problem that we have right now is we've learned a lot about disasters and about the causal factors of disasters and the creation the construction of risk, but we haven't been able to translate it, really effectively, into practice. We're getting better at emergency management, in some dimensions, particularly the initial stuff. But you very quickly transition to a kind of early recovery and reconstruction. And what we're doing, largely, is still reconstructing underdevelopment, reconstructing vulnerability. In Peru, the year after the disaster, I remember seeing a big--a big, banner, "No reconstruyamos el subdesarrollo," "Let's not reconstruct underdevelopment." So in Peru in 1971, they were framing it in terms of disasters are a problem of underdevelopment. We haven't been able to turn that into material reality yet. We're still reconstructing underdevelopment or still reconstructing vulnerability. Why is really an interesting and very important problem? And it's one of the things I like to really focus on right now. But right now I've got a full research agenda, the knowledge-practice gap. And I'm not blaming people. I'm not saying, "Oh, the practice people just don't understand or don't know." It's why is it--what is it that makes it very difficult to translate the language and the concepts that we've learned about disaster causation into practice. And part of it is, I think, is the nature of the critique. The nature of the critique is a very difficult message, which is, "You are building societies that are vulnerable--which means that there's something wrong with your development.”

BUTTON: Oh, it's a critique of the wider, systemic problems that we have in society.

OLIVER-SMITH: Exactly. It's a critique of society, of the systemic problems of how societies develop and grow which is fundamentally a political, economic critique. And that's difficult for societies like the United States to absorb in a way that will change practice. And we see this playing out all over the place. Look at Katrina. Looks at what's happening in the reconstruction of New Orleans.

BUTTON: Or the reconstruction of Haiti. There's a failure . . .

OLIVER-SMITH: --or the reconstruction of Haiti.

BUTTON: Yeah.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yes, exactly--.

BUTTON: The thing I think we have to recognize--well, that's true that, in any academic field of endeavor, it's very difficult to go from creating a robust body of knowledge and translating it into practice, regardless whether the focus is disasters or any other policy-oriented study. That's a bridge that's hard to cross.

OLIVER-SMITH: Absolutely.

BUTTON: --but in this case, it's particularly hard to cross. Because our critique of society is one of which we're critiquing the maintenance of the status quo. And that threatens the powers to be.

OLIVER-SMITH: Precisely. This is, as I say, vulnerability. [This] presents societies with a very, very acute challenge to the status quo. It says, uh, "You're building disaster into your built environment and into your society. You're creating vulnerable populations." It's a very profound critique.

BUTTON: Profound because you're building in vulnerability, you're building in asymmetrical balances of power, et cetera, et cetera. It goes way beyond the disaster itself‑‑

OLIVER-SMITH: --and the nature of that inequality is along the axes of race, class, gender, and in certain societies, ideology or religion, all the ways that we have of creating the other. We, in effect, ask the people that society puts in a disadvantageous position. What we ask is that they absorb risk--that they, in effect, are the ones that suffer risk. We--our societies, benefit certain segments of the population with relatively high degrees of security and expose other people, by virtue of their social and economic identities, to higher degrees of risk, higher degrees of vulnerability. That is a very profound critique of a society and very hard for a society--to say, "Okay, we've got to do something about this" and then actually, in practice, do something. We have not been able to do that.

BUTTON: Primarily because, when you ask societies to absorb a greater degree of risk, what you're really doing is asking the state to become more vulnerable to the challenges that are made to its status quo and its actual powers.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah. Well, it is, in a sense, a willingness to question in some ways some of the basic organizational principles of the society. And so that's one of the reasons why I think it's been very difficult to move away from what is fundamentally a reconstruction of vulnerability or a Band-aid approach. We're talking about very profound changes here‑‑

BUTTON: --because we're trying to move beyond immediate remediation providing food, water, shelter, and those kinds of reparations, that you need in the immediate aftermath, to going beyond that to actually recreating a society or a culture and with new alternatives--

OLIVER-SMITH: Right, but there's always a very interesting tension in disaster recovery, between, people who want to reconstruct what was before and people who want to change what was before.

BUTTON: The old normal versus the new normal--

OLIVER-SMITH: --but it's not always those who have a pure vested interest in the old society. They are there--

BUTTON: --right--

OLIVER-SMITH: --no question. But there are other people, it's a little bit between the question of the economic recovery versus the psychological recovery. Radical--people who suffer disasters, in general, are not interested in an adventure in social change.

BUTTON: They want to [return] to the old normal. They want to return to what they knew was safe--

OLIVER-SMITH: --they would like to improve, perhaps, things from the old normal but they don't want to radically change it. And then there are people with really deep-seated economic and political interests in the old. And they want to reestablish.

BUTTON: Right.

OLIVER-SMITH: And this is where the concept of resilience becomes very interesting. Because resilience, we consider as a very positive thing. But there are some very negative things, from the standpoint of society. For example, racism is one the most resilient systems of thought you can think of. You come up with arguments against racism and racism figures a way around it. "Yes, but‑‑" Pre‑disaster systems are very resilient. And if they are really deeply embedded in patterns of wealth and power, they will reinstall themselves.

BUTTON: They'll reinstall those conservative roots as opposed to looking to more progressive alternatives.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yes. So this is the problem. This is one of those tensions in disaster recovery, between preserving what is important, from a cultural standpoint, and changing what needs to be changed, from a structural standpoint. And, when I say structural, I mean economic and political structures as well as engineering structures. And this is the thing about disasters, is that they're both social and material events. And the two really can't be separated, because, as I mentioned earlier--and, I'm paraphrasing David Harvey here, the built environment is a material instantiation of the social structure. If you look at the way buildings are built, it is a reflection of social of the social order. Bad buildings are buildings where people are poor.

BUTTON: And the arrangement of those buildings, is also reflection of the social order.

OLIVER-SMITH: Absolutely.

BUTTON: The spatial place arrangements are a reflection of it, as well.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah. I mean, in Latin America, where do poor people live? They live on unstable hillsides. They live in riverbanks and floodplains you know, in dangerous areas. So, if you look at what happened in Honduras, basically, it was the large majority of the dead were people who were recent migrants to the urban areas. And where did they live? They lived in shacks on the‑‑

BUTTON: --they lived on the margins.

OLIVER-SMITH: On the margins. and they, in effect, were those who--they were the ones who suffered the most, because they lived in the most unsafe regions and in the unsafe structures. But that was not something that was innate to them. That was a condition imposed upon them by the society. This is, as I say--what emerged was a radical critique of society, from the study of disasters. That is probably one of the reasons why we have not been able to translate what we've learned about the origins and causes of disasters into practice that effectively addresses those issues. Because we're not willing to. Political will is not there--nor, probably, is the political support for it, at this point, anyway.

[Pause in the interview]

BUTTON: [Up to this point] we mostly talked about challenges.

OLIVER-SMITH: We could talk about going into the disaster field now. One thing is that the field of disasters has really expanded.

BUTTON: It has expanded. Because in the early days, there would only be three or four of us, five of us, at the most, on a disaster panel. On any conference you could go to, there are several disaster panels. And many times, we're not even familiar with some of the other people doing the disaster research. And the field has expanded exponentially, not only with anthropology but in many other disciplines, so that it's become, almost, if you will, a substantive subfield, as opposed to just a minor subfield.

OLIVER-SMITH: I have to say that, for many, many years, I felt kind of marginal to anthropology. I was the anthropologist that did disasters. And occasionally, there would be enough people to put together a panel. But in disaster studies, I was marginal to disaster studies, because I was an anthropologist.

BUTTON: Right, not a sociologist.

OLIVER-SMITH: Not a sociologist or a geographer.

BUTTON: Right.

OLIVER-SMITH: --and also studying the developing world. But now it's much more. Just to give you an example, in 1996, I published an article in the Annual Review of Anthropology, which you know is state-of-the-art in terms of the literature and what a field is doing. And there were 167 references--in 1995--1996. I couldn't even begin to guess how many there are now--

BUTTON: --several hundred, at least--

OLIVER-SMITH: --fifteen years later, there are, I would say, no less than three times that number. And it's occurred to me that now, at fifteen years, I could probably write another article.

BUTTON: It would be an enormous undertaking.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yes, it would be an enormous undertaking. And that shows you shows you the vitality.

BUTTON: That's a testament to the vitality of the field.

OLIVER-SMITH: You know, at the SfAA [Society for Applied Anthropology] meetings and the and the AA [American Anthropological Association] meetings, I run into young researchers, who are doing really interesting work. And, you know, it's still not a huge field. But I think, to some degree, it's probably recognized as a field of--as a--it's not an anthropological topic. When I began--when I started, when it was kind of like, "Wow! You're doing something really unusual." And now nobody's really surprised that an anthropologist is actually studying disasters.

BUTTON: And, in actuality, since 9/11, any of us working in the disaster field, whether in anthropology or geography or any other academic field, have suddenly [getting] considerably more amount of attention--and--

OLIVER-SMITH: --oh, yeah--

BUTTON: --and also because, in the ensuing years, just since then, there have been so many more disasters of such magnitude and severity that suddenly people take note of us. We're no longer these obscure academicians working in a small subfield of whatever discipline we're working in. It's because a central concern and central source of debate for people in the wider society and for the media and for politicians.

OLIVER-SMITH: One thing is that the disaster in 1970 in Peru was the beginning of what you could call the international disaster aid. 144 nations donated aid to Peru in the aftermath of that disaster. It was the biggest thing in the history of the Western Hemisphere. And up until Haiti, it was still the biggest. Now Haiti, with 300,000 dead is a disaster of much greater proportion. What happened was, in 1970 you had the Peruvian--the big disasters beforehand, but the international response was nowhere near what it was. But you have Peru and then you have Guatemala and Nicaragua. And you have the Tangshan earthquake in China, which killed, you know, close to a million, if I'm not mistaken--

BUTTON: --easily.

OLIVER-SMITH: --800,000 or something like that. And China, interestingly, at that point in time refused all international aid.

BUTTON: Right.

OLIVER-SMITH: And I think the media has played a major role in this, in bringing, in a firsthand way, footage and eye-witness accounts, of these terrible events. The field of disaster research and particularly the anthropology of disasters has been a reflection of the intensification of understanding of those events.

BUTTON: --and the increasing preoccupation of our society about those events that at one time was of little interest to most.

OLIVER-SMITH: Right. I mean, it was, "Something terrible happened in the developing world. Well, you know terrible things are always happening in the developing world and let's go on with whatever we were doing." Well, now we understand the enormous human impact, the terrible loss that these events occasion. And I think the media is partially responsible for that, and that has nourished an interest and an appreciation. And, of course, this all coincides with the development of NGOs. And NGOs respond, governments respond.

BUTTON: It's promoted the development of NGOs.

OLIVER-SMITH: Exactly. [In] a lot of ways.

BUTTON: There are now thousands of NGOs that respond to disasters. The number of NGOs in Haiti is a phenomenal number in itself. I can't even remember. There are hundreds of NGOs.

OLIVER-SMITH: No, I think it's something like 10,000. The development of the anthropology of disaster has been part of a much kind of larger phenomenon. And now disaster studies and disaster research, in effect, tie in with development studies with political economy. They're no longer isolated as this, kind of, extreme. But they are part--they're one thread, in a fabric or piece of a rope that are interwoven--and interface with development, with political ecology, political economy, very much a part of a much broader field--and ecology too.

BUTTON: Yes. I think, also, what's adding to that increased consciousness within our culture is that, in the beginning, especially in the seventies, we had the advent of so many technological disasters. We had Three Mile Island. We later had Chernobyl. We had Bhopal. We had a number of disasters, in the developed world, of significant severity and magnitude, that drew our attention home to ourselves and called us to question how it is that our technology and our impact on the environment has made us vulnerable as people in the developed world, as opposed to simply seeing the people in the third world being more vulnerable.

OLIVER-SMITH: Absolutely. I couldn't agree more. I think what we've really become much more appreciative of is the degree to which our own pattern of development has created risks.

BUTTON: Right. And that they're an enormous course to our populations, to industrialized, developed countries--just as there are in underdeveloped countries, that we're all now at more risk because of these policies, as globally as opposed to simply differentiating between developed and undeveloped nations.

OLIVER-SMITH: Absolutely. And I think, you know, what's transpiring right now in Japan is an outcome of a particular pattern of development, energy-intensive industrialization. This is the fundamental dilemma of our age. Our global society cannot continue on our present trajectory.

BUTTON: --particularly because, in events like in Chernobyl, lesser degree, Three Mile Island, and certainly the recent crisis in Japan, the vulnerability that is presented to a population is not simply the vulnerability of the people in Japan but the vulnerability of people around the world, who could be contaminated by radiation.

OLIVER-SMITH: Right.

BUTTON: We no longer see ourselves as living in a small world you could worry about the outfall of cesium-137 in North Carolina as well as in Europe, and, it's no longer simply, "It's over there"‑‑

OLIVER-SMITH: --yeah, right--

BUTTON: -‑"It's some other country."

OLIVER-SMITH: --I remember the image used to be fortress America; you know that we were-

BUTTON: --we were immune to--

OLIVER-SMITH: --we were immune--

BUTTON: --these kind of events.

OLIVER-SMITH: But these kinds of hazards don't respect political boundaries or even geographic boundaries at this point. So, certainly the beginnings of really serious technological disasters, that are part and parcel of the development paradigm, Bhopal, for example. And so here is where disasters link up with issues of sustainability and other security kinds of issues, the issue of our whole pattern, for example, of agricultural development is dependent upon pesticides and herbicides and things like that. These create hazards and we impose these hazards on people--.

BUTTON: --including ourselves.

OLIVER-SMITH: Including ourselves. But even within our own societies, yes, we all suffer--or we all are exposed to risk. There are some people who are exposed to more risk.

BUTTON: It's disproportionate.

OLIVER-SMITH: Disproportionately. The location of toxic waste disposal units--

BUTTON: --right--

OLIVER-SMITH: --in African American communities in the South. This is simply imposing this burden of risk on a certain population.

BUTTON: But one of the interesting things about technological disaster is that it really changes our notion of vulnerability. Because in that case, all citizens of the world, regardless of race, class, gender, et cetera, become critically vulnerable to something like radioactive fallout, because it can be distributed around the globe, regardless of what neighborhood or area you live in regardless of whether you're wealthy, poor, black, or white.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah.

BUTTON: And it has a shock value, that goes beyond the, uh--

OLIVER-SMITH: --yeah. This is, I think, something that I mean, what we're seeing right now is a questioning of nuclear energy production.

BUTTON: And energy production, in general.

OLIVER-SMITH: And energy production, in general--but particularly nuclear.

BUTTON: Nuclear.

OLIVER-SMITH: And it's interesting that the response of the government has been to affirm nuclear production. I don't think that people are entirely saying, "No." We need to rethink this.

BUTTON: Well, we know that, in the wake of TMI and then, later, in the wake of Chernobyl, that nuclear power production was severely restricted. Because the populations throughout the world felt too threatened by it. It was impossible for the interests in nuclear power industry to overcome that. And this may well be a third setback, that will prevent nuclear power from being this important part of our future, as some people, including our president, would like to think.

OLIVER-SMITH: But we all know that the window or the opportunity for change that emerges from disasters is relatively short, that the idea of reconstructing in a way that reduces vulnerability. The opportunity is there. But remember there is always the pressure to reinstall the old system. And that opportunity becomes narrower as you move further into the reconstruction process. And so, yes, right now there's a deep questioning of nuclear power. But as--unless we see this--the Japanese disaster, become totally uncontrollable‑‑

BUTTON: --well, as of today, 70% of the rods in one containment area are thought to be in the process of meltdown. So we're now actually in a catastrophic situation. So.

OLIVER-SMITH: Okay. Then that window may be prolonged.

BUTTON: That may be prolonged. In the case of, let's say, TMI and Chernobyl, it may be many years, or decades before people try to reinstall nuclear power but we know eventually they will, just as they have most recently. So there might be a setback now of greater duration than in most disasters. So it might be two or three decades down the road before the idea is reintroduced. But it will persist.

OLIVER-SMITH: Yeah.

BUTTON: The cycle is simply longer than in the wake of most other forms of disaster.

OLIVER-SMITH: So, anyway, I'm glad that you introduced the idea of technological disaster. I've not worked in technological disasters that much. But there is no question that now, technology has joined with the natural environment to produce forces that are capable of producing disasters. Technology, in and of itself, is not a disaster. An earthquake, in and of itself, is not a disaster.

BUTTON: Right.

OLIVER-SMITH: It is only a disaster when it meets a vulnerable society. And so it is society that converts those hazards into disasters. And I think that is a really important message, that we've been able to get across. Going back to our problem, how do we translate that into effective action? And that, I think is a really important challenge. And for younger anthropologists who want to get involved in this field, and particularly applied anthropologists.

BUTTON: Particularly in the face of global climate change, which is perhaps the greatest threat that we face in various guises, in the coming decades. That's probably going to provide us with the greatest challenge. But also, the stakes are so much higher now, then they've been in the past.

OLIVER-SMITH: --Yeah, precisely. And in sense, the whole issue of global climate change, for me, brings the stream of disaster research together with the stream of displacement resettlement research. And that's what I'm doing right now. And my research, right now, is on climate change adaptation.

BUTTON: And the inevitable displacement that's going to occur as a result of climate change--is already occurring, in some quarters of the world.

OLIVER-SMITH: It is also a very complex issue. There's no linear relationship between climate change, and disasters and displacement. The linkages are complex. We need to be cautious not to get involved in kinds of apocalyptic scenarios.

BUTTON: Right, right.

OLIVER-SMITH: We need to question what is it that adaptation really means. Does adaptation mean simply adjusting to a bad status quo? That's really not what we should be meaning by disasters by adaptation. So right now what I'm trying to do is to--I'm writing research grants to look at climate change adaptation in the Andes with a colleague at the United Nations University, where I had an appointment for four years, and a colleague at the Catholic University, in Lima. We want to put together a multisite research project, on climate change in Peru.

Further Reading

Anthony Oliver-Smith. 1986. The Martyred City: Death and Rebirth in the Andes. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press.

Anthony Oliver-Smith. 1996. Anthropological Research on Hazards and Disasters, Annual Review of Anthropology, 25: (303-326).

Anthony Oliver-Smith. 2005. Applied Anthropology and Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement. Pp. 189-220. In Satish Kedia and John van Willigen. editors. Applied Anthropology: Domains of Application. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Anthony Oliver-Smith. 2013. 2013 Malinowski Award Lecture: Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change; The View from Applied Anthropology. Human Organization 72 (4): 275-282.

Cart

Search