An account is required to join the Society, renew annual memberships online, register for the Annual Meeting, and access the journals Practicing Anthropology and Human Organization

- Hello Guest!|Log In | Register

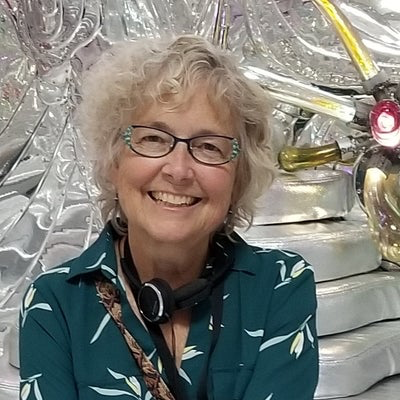

Interview with Madeleine Hall-Arber

November 1, 2019

An Oral History Interview with Madeleine Hall-Arber:

Understanding the Impact of Regulatory Change and Development on New England Fishing Communities and Beyond

Madeleine Hall-Arber has focused her research on fishing communities since 1975 when she devoted her summer fieldwork as a Brandeis University graduate student to accompanying Portuguese-American commercial fishermen on their fishing vessels out of Provincetown, Massachusetts. She later received a PhD from Brandeis. Her research on the impacts of regulatory change on fishing communities has led to her serving on a variety of advisory boards for fisheries management with the goal of helping managers identify ways to mitigate the impacts of their decisions. Her published work on New England fishing communities serves as the basis for describing the human environment for several fishery management plans. She has worked closely with fishing industry representatives on collaborative research projects, and she has also worked with the industry on improving fishermen’s safety at sea. Throughout her career she has been affiliated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sea Grant College Program, where she serves as an Extensionist Researcher. This interview was done by Barbara Jones, Brookdale Community College, New Jersey, on August 12th, 2008. It was edited for accuracy and continuity by Susan Abbott-Jamieson and John van Willigen; added material is presented in brackets.

Madeleine Hall-Arber has focused her research on fishing communities since 1975 when she devoted her summer fieldwork as a Brandeis University graduate student to accompanying Portuguese-American commercial fishermen on their fishing vessels out of Provincetown, Massachusetts. She later received a PhD from Brandeis. Her research on the impacts of regulatory change on fishing communities has led to her serving on a variety of advisory boards for fisheries management with the goal of helping managers identify ways to mitigate the impacts of their decisions. Her published work on New England fishing communities serves as the basis for describing the human environment for several fishery management plans. She has worked closely with fishing industry representatives on collaborative research projects, and she has also worked with the industry on improving fishermen’s safety at sea. Throughout her career she has been affiliated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sea Grant College Program, where she serves as an Extensionist Researcher. This interview was done by Barbara Jones, Brookdale Community College, New Jersey, on August 12th, 2008. It was edited for accuracy and continuity by Susan Abbott-Jamieson and John van Willigen; added material is presented in brackets.

JONES: Could you give me a little background into how you got into anthropology in the first place?

HALL-ARBER: Okay. I was going to the University of California at Berkley---

JONES: Okay.

HALL-ARBER: ---as an undergraduate, and I couldn't decide what I wanted to do. So I majored in social science, a field major, which gave you a little bit of everything.

JONES: (Laughs)

HALL-ARBER: And, I had a wonderful professor of folklore, Alan Dundes, ---

JONES: Oh.

HALL-ARBER: ---who is very well respected in the field of folklore, and actually in anthropology too. But [in] any case, he was fantastic. And people would flock to his courses. They'd sit in the aisles just to listen to him. I mean he'd have 350-400 kids there just to hear him speak. So I ended up getting my masters in folklore under Dundes. And then --I had done a field work project in the Caribbean, so I wanted to broaden [my studies] because I didn't feel that it would be very easy to get a job in folklore. And so I thought anthropology would be the appropriate step. And because I had done fieldwork in the Caribbean, I looked around for somebody that would allow me to keep the Caribbean focus, but perhaps broaden it, as well, to Africa.

JONES: Um-hm.

HALL-ARBER: Because there's so much influence, and I wanted to just to keep the connection with folklore, and yet move on. So I looked around and I found, [the] Brandeis Program, which had a little bit of folklore, not very much. They had a summer fieldwork program to help train you in the Caribbean. So I thought, perfect.

JONES: Oh.

HALL-ARBER: So unfortunately, by the time I got here, they had lost their funding for the Caribbean fieldwork--(laughs)--and they hadn't given tenure to the folklorist--(laughs)--so ---

JONES: Those are some serious issues there.

HALL-ARBER: ---you know how things go when you go into a PhD program, and I wasn't alert enough at that time, also it wasn't as common, I don't think, for people to go around and visit the school before--

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: --they actually signed up--(laughs)--so I didn't do that. I just came and oh, uh--those were just two of the disappointments, shall I say. So with the fieldwork project, we had to stay in the Boston area. And--

JONES: Oh.

HALL-ARBER: --that was not what I wanted to do. So I kind of looked around the Boston area and said, well, where can I go that's still considered the Boston area and is at least a little exotic, you know--(laughs)--a little different? So I went to Provincetown, which is on the very tip of Cape Cod.

JONES: Okay.

HALL-ARBER: And it's a fishing community. And so what I'd do is, I'd go down at four o'clock in the morning and hail a captain going out, and ask if I could go out for the day because they were just day boats--(clears throat)--and they all, with the exception of one captain who didn't know me, and--well none of them knew me at first, but eventually people recognized me--but this one guy wouldn't allow me to come because it was blowing that day. So I went out with somebody else who did know me. So it was--that gave me the vocabulary to understand the fishing industry, even though, you know, it was a very basic project for a summer fieldwork project. You can't really do a whole lot.

JONES: Did you have any issues to overcome the fact that you're a female?

HALL-ARBER: Well, interestingly, not with the fisherman. And, you know, they all--there was no problem. They welcomed me onboard, and when they would bring up their nets, they would dump the fish. I don't know how familiar you are with the industry, but they would dump the nets right on the deck. And then they'd have to sort them before putting them down in the hull. They'd put them in fish tubs--

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: --according to their species, and size, and that kind of thing. So I'd help them sort. They always loaned me the gear that, the water repellent gear and stuff, and often boots even. They had extra pairs--(clears throat) --so I'd be out there--(laughs)--digging through the pile filled with “gurry” they call it. You know it's this slime from the fish. And, I really looked like a sight. But they would get on their radios and tease each other about having this female graduate student in her bikini on their--(laughs)--boat. Well of course all the women monitored the radios at that time because it was public, you know.

JONES: Right, right.

HALL-ARBER: And so, I don't think the women were too thrilled that I was out there, but the men never gave me a hard time. And it was all good, good humor. You know, it was all--nobody ever hassled me at all. And actually, you know, most of the women too--I eventually met a lot of the wives and, and they were fine too. They were just, just a little bit annoyed because most of the time women, especially--women--I don't know if--maybe because they were wives--weren't welcome onboard the boats, except during the blessing of the fleet. It was still considered bad luck. In Provincetown, it was a Portuguese-American fleet. And there were some Portuguese fishermen too, but I didn't try to go onboard because I didn't speak Portuguese, and a lot of them were not very fluent in English. So I went with the guys that could speak English, who were mostly Portuguese-American. But anyway, that ---no, it was not really a problem. And then from there, after doing my summer fieldwork project, when I presented it at Brandeis, one of the professors who had done her fieldwork in Africa asked if women ever actually fished. And there were one or two women--maybe one woman that summer--who fished on a lobster boat, but other than that, there weren't any women that were actually doing the fishing. There were a lot involved in the business, but not going out on the boats actually fishing. So, this professor thought that in, in Senegal there were women who actually fished. So she thought I might want to--since she knew I was interested in African women, that I might want to look into that. So I did and--(sighs)--as it turned out, where I ended up staying, which was in the north part of Senegal, right at the border with the Mauritania, in fact it was Saint-Louis. They were supposed to open a centralized market and I wanted to look at the impacts of development projects on traditional-organization fishing communities.

JONES: Now how did that go--so the folklore moved into this more applied approach with fishing?

HALL-ARBER: Yeah, and that was only because of that summer fieldwork project that I just became very intrigued by the industry.

JONES: I see. Okay.

HALL-ARBER: And, and then, the folklore --because there, there was nobody at Brandeis who had the least interest--(laughs)--in folklore-- that kind of went by the wayside. So, I didn't, didn't follow up on that, much to Dr. Dundes’ consternation--(laughs)--he really wanted me to go to the PhD in folklore at Indiana University, which I almost did. But, anyway, so, so yeah. That's, that. I moved into that. I was very interested in development projects anyway because of, you know, the Caribbean is kind of right on the cusp between, being, at that time, considered sort of underdeveloped and tourism focused. And, and so I thought Africa, of course, was the same way. It had a lot of countries where they were pouring --World Bank and AID were pouring-- a lot of money into the countries to try to raise up their standard of living, I guess. I knew from my reading that the centralized markets were apt to disproportionately negatively affect the women because the women were the ones that do the marketing.

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: And so, they were the intermediaries--and all these articles that you read that say get rid of the intermediaries and [in] fisheries, and then the fishermen will bring home a lot more money. But what they didn't recognize was the role that these people played not only in actually just physically selling the fish, where the men were out fishing [and] weren't relaxing after a hard day fishing. They were risk-taking, and various other--and more importantly from my perspective, is that the women--this was a polygamist society--the women had very important economic roles in paying for their kids' education, helping pay for the household, food, and so on and so forth. So it was a bad idea to try to get rid of the women's work--(laughs)--basically is what it came down to.

JONES: Disenfranchise them completely.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah, yeah, and as it turned out--again, my timing has been off in, in my career a lot--(laughs)--but there was supposed to be a centralized market that opened in Saint-Louis. It was supposed to open two years before I got there. It opened the day I left--(laughs)--and, actually not only that, it was [that] they had moved it from Saint-Louis down to right outside of Dakar, and so it was not something I looked at. So essentially what I did was a baseline study and showing the importance of the small-scale earnings because these women did not earn a lot of money, but they managed to do--they'd form groups and they managed to, to do a lot with the little that they had. So that's what my dissertation focused on. And then when I came back here, I had been working as a graduate--when I was a graduate student at Brandeis, I had been working part time here at Sea Grant, and just doing secretarial work. And, but I really liked the idea of Sea Grant. I thought, you know, marine related--they support marine-related research and they have an outreach segment of a portion of the program. So I thought great, you know, if I can do something at Sea Grant, that would be fantastic. So, when I came back from the field, I worked -essentially, as a freelancer, for about a year before the job I'm in now opened up.

JONES: Oh, so you've been here since you finished school.

HALL-ARBER: Yes. I've been here for a long time--(laughs)--and--

JONES: But that's wonderful.

HALL-ARBER: It is. It worked out beautifully because when I first arrived, I was still working on my dissertation for many years. And, so I did the outreach portion. Focused mostly on coastal zone management activities, but then when I finally got the PhD and had some opportunities, they started doing --I was asked to do a social impact assessment for the ground fish plan, and, which is the main, the multi-species fishery management plan. And--(sighs)--let's see. It was in the early 1990s. Well, actually, it was in planning for, for almost ten years, I think, when they finally passed it in 1994. But in any case, they had asked me to work on that. That was out of NOAA Fisheries [which] has Peter Fricke, who is--

JONES: Oh I know.

HALL-ARBER: You know Peter?

JONES: Yeah.

HALL-ARBER: He's actually a sociologist, but a British sociologist, which is really an anthropologist here. So, you know, he fit the anthropologist, so he was very supportive of anthropology. And he really wanted us to do, to get involved in, the management process. And he invited various people actually to work in the NOAA headquarters too. So there's been a tradition of some anthropologist getting involved with NOAA Fisheries. And, so my job became more towards the research end. I still do some outreach work, but usually with the fishing community.

JONES: Do you have a regional focus?

HALL-ARBER: Yeah. Mostly the Northeast, but because there are not a whole lot of anthropologists who are involved in fisheries, I have been invited to Alaska, and to California, and to serve on various committees on the two coasts for addressing certain social impact assessments mainly.

JONES: So you look at how current laws and things impact community-based management and all that sort of thing?

HALL-ARBER: That's right. Yeah.

JONES: Oh, okay.

HALL-ARBER: And how, first of all, how communities are likely to be affected by changes in management, and then try to figure out if there are two choices that will accomplish the same goal, try to encourage the managers to choose the one that will have the best sort of impact on the community. And in order to do that, you have to know something about the community.

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: So I've done some work--sometimes, sometimes with teams of people, looking at fishing communities, and how they're organized, and what they think will be the likely impact.

JONES: Is there a real positive relationship between the fishing communities and your group?

HALL-ARBER: Quite a, quite, yes.

JONES: Okay.

HALL-ARBER: And it--of course it depends on the individuals, but I've had a lot of support and a lot of people willing to talk to me. And, I've collaborated a lot with organizations like the Massachusetts Fishermen's Partnership, and less formally with SMAST [School for Marine Science & Technology]. I forget what that stands for. It's the, the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth's Science, Marine Science Center.

JONES: Okay.

HALL-ARBER: And, they've been, and, and the city of New Bedford actually have co-sponsored safety training programs for commercial fishermen. So I've gotten involved in helping organize those. I've done that up here as well in various places, actually, along the coast.

JONES: So, then your role would be also interceding with --when fisheries are closed, or because there's a fish, that sort of thing, you kind of--

HALL-ARBER: Well, what I do in that case is, try to, again, look at the impacts to try to anticipate what the effects are going to be, and then at least make managers aware so that they're not making their choices in a vacuum. It doesn't always help because they, they need to make the choices they make anyway if the fish--because legally there are, there are ten national standards in fisheries. And the impacts on fishing communities is the eighth. So it's low on the list of priorities, you know, and so their most important goal is to make sure that the stocks are, are healthy, and there's a lot of debate about whether they go about it the correct way, and whether or not, it's really as necessary to be as harsh because they need to make sure that there's no overfishing --overfishing is not occurring, and that the stocks are rebuilding. And they want them rebuilt within a ten-year timeframe. Well it's been fourteen years I guess since then, the first serious management plan was put in place, for ground fish. And there are a lot--they've been somewhat successful. Haddock has come back, and some of the cod has, but there are certain stocks of yellow-tailed flounder, for example, and certain stocks of cod --because they break them up into George's Bank Stock, Southern Maine, or Southern New England Stock, and some of them are probably on their way to being rebuilt. Some aren't, but because they travel, they get all mixed up, so when you're using any kind of gear, you can't really tell what you're getting…

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: …until it comes up on deck, and by that time it's too late. So it's been very problematic and their--the regulations are harsher and harsher because they, they are stuck with this five--or this ten-year deadline. And, the feeder kind of helps the fire by the environmental groups who sue if they don't feel the managers are making a serious enough effort. The concern in the fishing community is still pretty low. You know it's been--a lot of the fishing communities say, "Well, you know, it's fine. We're also concerned with the stocks coming back. We want our children to go fishing. We want a sustainable livelihood." But the way it's going, there are not, there are not going to be any fishermen left when the fish come back, so they talk about … what about sustaining our fishing community? So, it's a huge problem.

JONES: In New Jersey we have a conflict where--well, two ways--the anecdotal evidence-- the fishermen’s side, says this [these] fish stocks will rebound--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: --and then the cost of living in fishing communities.

HALL-ARBER: Right, right.

JONES: That's the death knell now for many of them. They have to leave because the property taxes and the real estate--it's coastal property.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah.

JONES: So that's our biggie, I think that we're dealing with.

HALL-ARBER: We have that as well, although there are a few communities, like Gloucester and probably New Bedford too, are designated-- they have designated port areas and that has to have marine-related development, marine-dependent use, so that's protected them for now. But there's a constant push to get that changed. And, even with that protection, taxes do go up, and it, it is difficult for people to continue when they don't have enough fish coming in.

JONES: Right, and then there's the issues of safety for some of these boats that go out.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: It's serious business.

HALL-ARBER: Well yeah, we lost a good --really a fantastic, fisherman just a couple weeks ago and everybody is still reeling from that. He was a very bright guy, very active in collaborative research and worked quite closely with the government managers, the government science managers, to try to come up, for example, with selective gear that would only choose the species that were plentiful. And, he was squid fishing and, and luckily, they were able to save his two crew members, but, you know, when you see that happen, when a boat goes down--

JONES: How far offshore was he?

HALL-ARBER: He was off- -I mean it was off New Jersey, actually about fifty miles, and his boat just, I guess--I think there had been some hurricane down south a bit, and so it had caused a sudden--

JONES: Swell.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah, a sudden change in the patterns. And the boat--he was struggling to straighten up the boat and it flipped. The crew members, luckily, had gotten off. I don't think they even had their survival suits on it was so fast. But it was summer, so--

JONES: Luckily the water wasn’t bitter cold, although-

HALL-ARBER: Yeah--

JONES: Sixty-five when it's warm. I don't know.

HALL-ARBER: Oh gosh.

JONES: Oh my goodness. So, do you see applied anthropology then is much more useful than the traditional and theoretical-based?

HALL-ARBER: Yes. I, even as a folklorist, I was really not that interested in theoretical aspects. I was much more interested in--and, and actually that's probably one of the reasons I moved into anthropology is because I didn't want to end up just being in academia. It didn't appeal to me. It's fascinating that someone's theoretical reading is very interesting, and can be useful in applying anthropology, but I wanted to do something that might have a beneficial impact for people.

JONES: So, do you see the future of the discipline more towards the applied, or…?

HALL-ARBER: I think that there are more opportunities now probably. I think more people are able to get jobs in industry and other places. I mean there--a, a lot of times at least the talk says we have to pay more attention to the human factor.

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: And so, it makes sense that people would look at organizational structures, and, and, various aspects that applied anthropology--has been the forte of applied anthropology. So yes, I would say, to some extent anyway, that there are probably more opportunities, and--but, you know, academia has a very strong siren call for a lot of people. And, and there are a lot of people, of course, that just really get immersed in theory and like the idea of focusing on theory, theoretical aspect[s].

JONES: But I think, for me, I see, with applied, it's much easier for an undergraduate to get the handle on it, and, you know, even get a job.

HALL-ARBER: Yes.

JONES: Get a job in the government. You can get a job--marketers, you know--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: --all sorts of things---

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: ---I think thirty years ago most anthropologists would not even consider.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: So that's, that's interesting. Well, what would you say your success stories in anthropology have been?

HALL-ARBER: I think probably because there were so few people that were doing social impact assessments in fisheries management, fisheries management really started in earnest in 1974 when we passed the Magnuson-Stevens Act. But it wasn't until really 1993 that there was much social impact assessment done, even though that was supposed to be part of the management plans. It was also new to people. I think my first work was one of the first pieces of social impact assessment. That's not entirely true because in the seventies there were [John] Poggie, and [Richard] Pollnac, and Jim Atchison did some profiles of small fishing communities in New England.

JONES: With the lobsters too, right?

HALL-ARBER: Oh, Atchison has done a lot of work for--long before I came on the scene.

JONES: Is he Maine?

HALL-ARBER: Maine, yeah, but lobsters, at that time, were managed only by the state. So I'm talking about the federal level.

JONES: Right, right.

HALL-ARBER: So, Atchison, he had a whole group --Atchison, Poggie, Pollnac--I forget who else was in the team, did --and had an NSF Grant, and they did profiles of fishing communities in New England--and that was probably--so they were sort of my mentors. And Susan Peterson worked for the Woods Hole --Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, and she's an anthropologist and she also was very interested in fisheries. And so, so there were people around doing the work, but it wasn't yet incorporated officially into the management plan[s]. So, my--the work that I've done--and again, some with teams, has allowed me to at least make a, make a stamp--(laughs)--on the need for looking at fishing communities, and officially recognizing the importance of fishing communities in fisheries management. I don't think it's made a huge difference yet in what has actually been done, and that's because of all the, the legal suits. We did--the, the--I felt that our work when Amendment Five to the Multi-species Fishery Management Plan was being designed--at first, they were going to make major changes, radical changes, right off the bat--and we encouraged them to phase them in. So that was the plan. It was going to be a five-year phase in.

JONES: Um-hm.

HALL-ARBER: Then the next year there was an assessment that said that the cod was on the brink of collapse. So they put an Amendment Seven and it completely, you know, [clap] squished everything. So all of the, all of the changes were made right away instead of phased in because they were really fearful that the stock was really going to collapse. I keep feeling like we're making some progress, and then there's a throwback. So I'm not sure I could actually say we've had a tremendous amount of success in actual change, but I think that there has been a fair amount of success in awareness--and developing an awareness--of the need for looking at communities. I think that the collaborative research movement came partly from realizing that the industry members--and this can be fishermen or people ashore--have a lot of knowledge that is useful to the management process, so I think I made a contribution there. I think also with the safety training. That has been a very large contribution, and again, because I do so much collaborative research, I can't say “I did this” --(laughs)--you know. I can't take, you know, credit for, for much of anything as being--

JONES: But you're part of it.

HALL-ARBER: --but I'm part of it, and that's what actually I wanted was--and I've always wanted, just to work with other people so that you're helping change people's capacity to understand what's going on and to make changes that are based on a broader range of people's views, helping with [the] visioning process of how do we want to move forward, and what goals do we have? For example, some communities, they talk about wanting--well not really communities--a lot of economists will say they want to rationalize the fisheries and make it more efficient. And what that means usually--it's usually code--those are usually code words for moving to individual, transferable quotas, and that's so that everybody has a little piece of the pie that they can buy or sell, and then they can make their decisions about fishing based on that, on what they know that they are going to be allowed to catch. What ends up happening is that the industry consolidates. There are many fewer owners, fewer boats, those owners make more money usually. The crew makes less, and the support services are narrowed. So it--perhaps it allows more tourism because property falls by the wayside. It's no longer used for marine-related use, or it could be used for yachting or whatever, but it's not used for commercial fishing. So, then there are other people who say, "We don't want that. We want to maximize employment. We want to have our small boats. We want to have--we want to go out fishing for a day and come back. We would like to provide for the high-end restaurants so that we make a fair amount. We take good care of our few fish that we catch, present them to somebody who cares about them, and prepares them well, and allows my kid to go fishing and not have to buy an expensive permit that will mean he has to fish in a very efficient way." So there are different goals for people. And so what I've always tried to encourage is a diversity in the fishing fleet, and in the fishing communities, and in the business, so that you do have room for the more efficient operations--the larger boats-- but you also maintain a sector of smaller, and medium-sized boats because they can function very differently. They have different costs involved and it has a different impact on the community.

JONES: How do you integrate the two though? I find, like in Belford, [New Jersey], there's a lot of competition with the small guys compared to the big fleets.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: They don't like them at all.

HALL-ARBER: Well, that has been more true, I think, even in the past.

JONES: Well they tend to think of the past a lot.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah, that's right--(laughs)-- and it is true that I--in fact, I wrote an article years ago about--it was funny. It was for a publication that the Northeast Sea Grant put out, and the graphic artist did a really nice job of having people pointing in different directions--there were just arms pointing in different directions. And it is true.--everybody pointed to somebody else as being to blame--

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: --for the way the status of the stocks is, and the economic condition of the fleet, or the community, or whatever. But--and in fact-- different gear groups are very competitive. We have the fixed gear, which are the lobster boats --the gillnetters, are very antagonistic towards the trawlers, who they feel are likely to run over their gear. And then you have the longliners, who are holier than thou, and feel like that their way of fishing is much more ecologically sound, and so on and so forth --but then you'll hear some fishermen who say, "Look, I've fished every kind of gear there is in existence and they all have their positive aspects and they all have their negative aspects. So don't go all holy on me,"--(laughs)--

JONES: It's not working.

HALL-ARBER: Right. So you know, the longliners will maybe catch more juvenile fish. Mesh sizes affect what size [of] a fish that you catch, and they can be fairly large. So they don't catch many juveniles. So it varies. You know there's just a lot of aspects to the different types of gear. There are people that complain that the trawlers have too heavy door[s]--you know those doors-- they say those are too heavy. And, but over the years, those have been changed to composites and [they have] more aerodynamic shapes, so they're not hitting the bottom like they used to. They've also changed some of the net configurations. So as I mentioned, some are redesigning them so they're much more selective of different species. I think some fishermen will say that it's better if the trawls are used only on sandy bottoms--not on hard bottom-- because hard bottom is where fish tend to have their refuge areas. So--but you know-- even that is disputed by other people. So it's hard to know exactly what's going on.

JONES: So, a disappointment would be then, maybe, that there isn't more of a shared understanding across the disciplines meaning--you know--you've got the environmental people--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: --you've got the government, you've got social scientists.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah. I would say yes. What's been very frustrating is that the collaborative research has had some very interesting outcomes--and very positive outcomes--both in getting the scientists to talk to fisherman, and the fishermen to talk to scientists. So they've been doing a really good job of communicating. It's taken awhile. I mean they had to learn how to talk to each other, for one thing--and council meetings are a little easier to understand than it [they] used to be. Now people--the scientists--seem to be making an effort to make themselves comprehensible to people who aren't trained in biology or assessment models—but, but there's not much money left for, for the collaborative research--and that's very frustrating because it seems to me that that's a way to integrate these different disciplines. And I also think that the managers should spend some time on the fishing boats so that they too understand what's going on. The same thing with the environmentalist. You know, there are a couple of environmentalists who have been out on fishing boats who are much more willing to negotiate, and willing to try to see if there's a way to come up with ways to make the fishing community survive--as well as the stocks, the fish stocks.

JONES: Do you see many environmental anthropologists in fisheries that would try and understand?

HALL-ARBER: Oh that's a good question.

JONES: I'm not sure I know any because that would be a very handy thing to have someone who is an anthropologist that studies the environment.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah, I don't know of any offhand. There's a woman who works for Green Peace who was their fishing coordinator--actually she used to work for Green Peace. She now works for the North Atlantic Marine Association--I think it's called NAMA. She lived in Gloucester and had really tried to understand the fishing community when she was working for Green Peace. And so--but she's not a trained anthropologist--however, I think her actions were more like participant observation, and so she had a better understanding of what was going on than a lot of people. But other than [that], I can't think of any [environmental] anthropologists that are working in fisheries.

JONES: That would just be, to me, a nice compliment to get the other side---

HALL-ARBER: Right, exactly.

JONES: ---you know, to look back.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah.

JONES: All right. Well that's interesting. So how do you see the applied anthropological writing for appealing to a broad audience? I know with theoretical writing it tends to stay in academia, you know, because nobody can read it.

HALL-ARBER: Right, right.

JONES: But, do you see applied anthropologists making an effort to write things that are appealing to a broad audience?

HALL-ARBER: I think to some extent. I think, in our particular field--in the fisheries--now there are anthropologists that are working for [the] National Fishery Service [NOAA/ National Marine Fisheries Service] on both coasts--and I think they are making an effort to at least provide the social impact assessments in a readable form, you know, and they are making--writing profiles of the fishing communities that do go out, back to the community, so that they have this information that's baseline. There was an anthropologist actually on a project--another collaborative project I've worked on--that worked with the harbor planning process in Gloucester to try to help--I was telling you at the beginning that they were--they had the marine designated area. Marine port--not NPA, it's DPA, Designated Port Area. All these acronyms, you know--(laughs)--

JONES: They drive you crazy, I know.

HALL-ARBER: --and, and since there was a lot of conflict in Gloucester about whether they should change that or not, she worked--we had a --our project had a-- what we called, a community panel. So one of the things that they were looking at is what the fishing industry needs to survive--what they absolutely have to have as a minimum for [a] working waterfront-- and so she brought that information to the harbor planning process. So, she linked up with [a] very practical application and had a positive impact, at least up to the point--you know, that

they-- it went through the process. It's a constant battle. So I don't think that she's working with them any longer, so who knows what will happen in the future. But for the time being, it was a good thing because it did help people become more aware of the tradeoffs. And I think that's a really--an important aspect--that anthropologists can help with, is focusing people on their long-term needs, not just the short-term needs.

JONES: How do you see public perception of you as an anthropologist? Do people understand what it is you do?

HALL-ARBER: I think more people do now, but--(laughs)--the general populous, no. I mean you, you still hear, "Oh, you dig bones?" (Laughs)

JONES: Yeah, that's what I get. You dig dinosaur bones.

HALL-ARBER: Right. Yes.

JONES: Oh my gosh. (Laughs)

HALL-ARBER: No, I say “more like Margaret Mead”, you know--but even that is no longer an explanation because she's so far [in our past].

JONES: Right. She's been gone for so long that the modern student only knows her as almost a caricature of what we once were.

HALL-ARBER: Right, exactly. So I usually have to explain, and I belong to a couple of organizations like that. For example, there's a women's fisheries network, and that involves women who are involved in any aspect of fisheries. So we have a dinner meeting two times a year. And we go around the table, or several tables, and introduce ourselves and say what our interest in fisheries is--and so I've trained those people--(laughs)--so it's a small group.

JONES: But you're starting to spread the word.

HALL-ARBER: Right. It's like the pebble, you know.

JONES: The ripple is working its way out.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah.

JONES: It's funny to overcome that.

HALL-ARBER: For in my first meetings with people, I usually have to explain--but not [for] everybody. I mean some people have learned over time.

JONES: They've got a grasp of it. Okay. That's good. So what do you see for the future of our discipline, applied anthropology? Do you have positive feelings?

HALL-ARBER: Oh yes. And I love [the] Society for Applied Anthropology--it's one of my favorite professional meetings. And I feel like there's, you know, a lot of enthusiasm still, and a lot of hope that we can have a positive impact on, on whatever field we're working in. There's a lot in medical and fisheries--one of the reasons the SfAA is nice for us is because there's a

--there's always a cadre of fisheries people that get together, and we usually have a few interesting sessions that somebody will organize. So that's really nice. But I think that--I'm hopeful that-- anthropology will continue to move into more practical applications in businesses –and the thing is-- that comes with negatives too because you do have people that are going to be working in, perhaps, areas that some of us from the old school are a little uncomfortable with, like there was that controversy over the anthropologists that work in Iraq, although, I have mixed feelings about that because I do feel “like of course they need anthropologists”-- you know--(laughs)--of course.

JONES: We [inaudible] the class and they're like yeah, I could see why.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah. My students all see that it's essential--so, but I guess there's always going to be some debate, even in marketing. You know, “Do we really want anthropologists to tell us how to eat more fattening food?” Or--(laughs)--you know--

JONES: Right, or what brand of toothpaste to buy.

HALL-ARBER: --so it's the old selling angle. I'm still--I'm from the late sixties, early seventies school of thought--so it's hard to think of people “working for the man” --(laughs)--or the--

JONES: So anti-establishment of you! I just can't stand it--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: I'm thinking, though, particularly for young people, the future of the discipline is not going to be in the PhDs.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: Okay, there's just not enough jobs--

HALL-ARBER: Yeah.

JONES: --but if you could get a good job as an undergraduate with training in anthropology, but that leads you to working for, you know, Verizon, how to design a new phone.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: I mean is that where we want to go?

HALL-ARBER: But you know I think that there is a role for, for anthropology, even as a PhD. I think that it's not a bad thing for people to get a serious training, and then move into business, because I think that the more we're all aware of how people organize the--

[Pause in Audio]

HALL-ARBER: --for people to just learn more about how human beings tend to work, and the differences--I mean we are becoming more homogenized--so I find that worrisome. I'd rather people all around the world retain their individuality, you know, but, of course with--

JONES: Well it's crucial for problem solving if we all remain somewhat different.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: It's a scary thing.

HALL-ARBER: I mean it's so boring too. (Laughs).

JONES: Well yeah. You know you travel to Egypt and you see a Kentucky Fried Chicken, and it's just like--

HALL-ARBER: Yes, oh come on--(laughs)--and people getting fatter, and fatter. It's so, it's so sad. So if--of course my preference would be for anthropologists to move into these fields and then solve the problems, you know, that are, that are plaguing our materialistic society so that we do have a more balanced existence, and, and not have all of these upcoming nations fall into the same difficulties that we did, and, you know, learn from our mistakes and move on. (Laughs)

JONES: Right, right.

HALL-ARBER: That's what I'd like to see.

JONES: So that would be a word of wisdom --as the last thing I needed to talk to you about-- for junior colleagues--would be you see [junior colleagues] getting advanced degrees.

HALL-ARBER: I think that that's a positive because, well frankly, I have been on some committees of some students who are trying to move towards [a] PhD and they just don't yet have the training, so I--and I feel like it's really essential for people to understand--the problem with anthropology is that once you start looking at--once somebody makes an observation [based] in anthropology--it's very easy for people to say, "Oh, I knew that", because it sounds like common sense--but unless you're very disciplined about it, it's, it's really not necessarily common sense--and you need to have that discipline and formal training, I think, in order to understand that --to really understand people, and to understand how to analyze [what you observe] in order to move forward.

JONES: And the methodology is crucial.

HALL-ARBER: Yeah--and, and I don't think that a lot of undergraduates are going to obtain that. Maybe in some of the finer schools--you know, not necessarily an Ivy League school--it could be a fantastic anthropology program anywhere. You know--I'm not saying that--but just that the way that undergraduate education is structured, I think it would be very hard for them to have enough of a background to make a significant difference. So, I would encourage people to go ahead and get the PhDs, but not with the plan to go to academia--to plan to go into some applied field, whether it's business or something else, but with that strong background.

JONES: The problem for so many students, though, is the cost and the time commitment.

HALL-ARBER: Oh, I know. I know. It's really shocking when you see how much education costs now.

JONES: Right, and degrees in social sciences don't pay very well, so there has to be some real incentive--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: --and that's difficult to overcome. Because you know, I teach undergrads and you see them--you work with them on these research projects, and they just--they're very easily discouraged--and they always want to know, “Well, what can I do with this when I graduate?”-- and we have to have a bigger vision.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: You know, that well, it's not going to necessarily be four years--you can't learn how to think like an anthropologist in an undergraduate program. You can start, but you're right--it takes original fieldwork to really get to doing it--

HALL-ARBER: Yeah.

JONES: --and somebody criticizing it, and talking to you about it, and all--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: --which comes with the graduate work and with experience.

HALL-ARBER: I mean even the newly minted PhDs --it takes time to really develop the knowledge base--and then it's time to retire! (Laughs)

JONES: So those are you words of wisdom. Get your PhD. Get some experience and retire. Okay.

HALL-ARBER: --but then you can write for the public! (Laughs)

JONES: There you go. That's right. You can write pop cultural novels or something. I don't know.

HALL-ARBER: Barbara Pimm did a great job of advertising--(laughs)--anthropology.

JONES: That's a good idea--so there's only the future for us.

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: And Elizabeth Peters--

HALL-ARBER: --the archaeologist. (Laughs)

JONES: That's true, with her whole Egyptian series.

HALL-ARBER: Right, right.

JONES: No, it is true, and I think a lot of historical fiction uses a lot of anthropological stuff--

HALL-ARBER: Right.

JONES: --it's just you don't think about it when you're reading it.

HALL-ARBER: That's right, which is the best way--

JONES: Right.

HALL-ARBER: --and that's also what I was saying is that once people, you know, kind of bring this information in, and make it their own, then it becomes a part of them, and that's what we want. We don't want people to say, "Oh that's an anthropology tidbit." You know? (Laughs)

JONES: Well that's why I tell my students [to] read a Tony Hillerman novel--

HALL-ARBER: Yeah.

JONES: --and they'll look [at me] and they're like, "Why would I want to do that?", and I said [say], "because he writes like an anthropologist, and you begin to understand another culture, and isn't that what it's all about?" And they're like, “Oh, oh, oh, that's stupid”, but they'd rather weed through Chagnon or something, and they don't even finish the book.

HALL-ARBER: Right, right.

JONES: So what have we accomplished there?

HALL-ARBER: That's--(laughs)--right.

JONES: Oh well. All right, well this was wonderful!

HALL-ARBER: Well it's great to talk to you.

Sample Bibliography

Madeleine Hall-Arber, C Pomeroy, and Colleen Sullivan. Combining geographic information systems and ethnography to better understand and plan ocean space use. Applied Geography, 2015.

Madeleine Hall-Arber and Flaxen Conway. Power and perspective: Fisheries and the ocean commons beset by demands of development. Marine Policy, 2014.

Madeleine Hall-Arber and Flaxen Conway. Figuring out the human dimensions of fisheries: Illuminating models. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 2009.

Madeleine Hall-Arber. The community panels project: Citizens’ groups for social science research and monitoring. Anthropology and Fisheries Management in the United States: Methodology for Research. Palma Ingles and Jennifer Sepez, Eds. NAPA Bulletin No. 28: 148-162, 2007.

Cart

Search